A cardinal arrives in Sheffield, on the way to meet his fate

A contemporary account offers a fascinating description of Thomas Wolsey's imprisonment at Manor Lodge

Good morning readers. This weekend’s long read is about Sheffield’s key role in one of the most significant moments in English history. In 1530, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was imprisoned at Manor Lodge for 18 days and died just a few days after he left. His fall from grace had implications for the kingdom that are still felt today, almost 500 years later.

The Tribune is looking for good writers to contribute to its vision of a new journalism for Sheffield. If you’re a freelance writer or you have ideas for stories, please email editor@sheffieldtribune.co.uk.

If you think a friend might find this newsletter interesting, please just forward it on, or you can use the button below to share it via WhatsApp or on social media.

By Dan Hayes

When Cardinal Thomas Wolsey arrived at Sheffield’s Manor Lodge on November 8, 1530, he was both tired and fearful for his future. Henry VIII’s erstwhile first minister had been arrested four days beforehand at his bishopric near York. He was to be transported to London on charges of high treason and was under no illusions about the fate that awaited him in the capital.

As Chancellor, Wolsey had been the second most powerful man in the land. Such was his authority in the 1510s and 20s that he was often named ‘alter rex’ or ‘other king’. As well as overseeing the church in England, the cardinal also exercised huge power over foreign policy, writing peace treaties and facilitating Henry’s wars. But successfully challenging the might of Rome over the king’s marriage had proved beyond even his great powers.

It is one of the best known episodes in English history. Wolsey had fallen out of favour after failing to negotiate an annulment of Henry’s marriage to his first wife Catherine of Aragon. The king needed the annulment so he could marry Anne Boleyn, but the Pope ruled that the decision was his to make, not England’s. Anne was furious and blamed the cardinal.

The failure to secure the annulment led to him being arrested and stripped of his government role in 1529. But he was allowed to remain Archbishop of York and later that year travelled to Yorkshire for the first time in his career. Historians disagree over whether the charges of high treason were trumped up by an angry Henry or well-founded allegations over a foreign plot. What is not in doubt is that in late 1530, he was visited by Henry Percy, the sixth Earl of Northumberland, and ordered to return to London to face a trial.

Wolsey set off by mule from Cawood in North Yorkshire accompanied by a huge entourage, making his way first to Pontefract and then to Doncaster. His escorts had hoped to keep his arrival in the town quiet by arriving under cover of darkness. But crowds still lined the streets with candles, some shouting ‘God Save Your Grace’ as the procession rode through the town.

After just one night in Doncaster, Wolsey was taken to ‘Sheffield Park’, where he would stay for the next 18 days. His time at Manor Lodge is chronicled in astonishing detail by George Cavendish, the cardinal’s gentleman usher, in his book The Life of Wolsey. From his account we know both how his master lived at the lodge and how the illness that ultimately killed him first manifested itself.

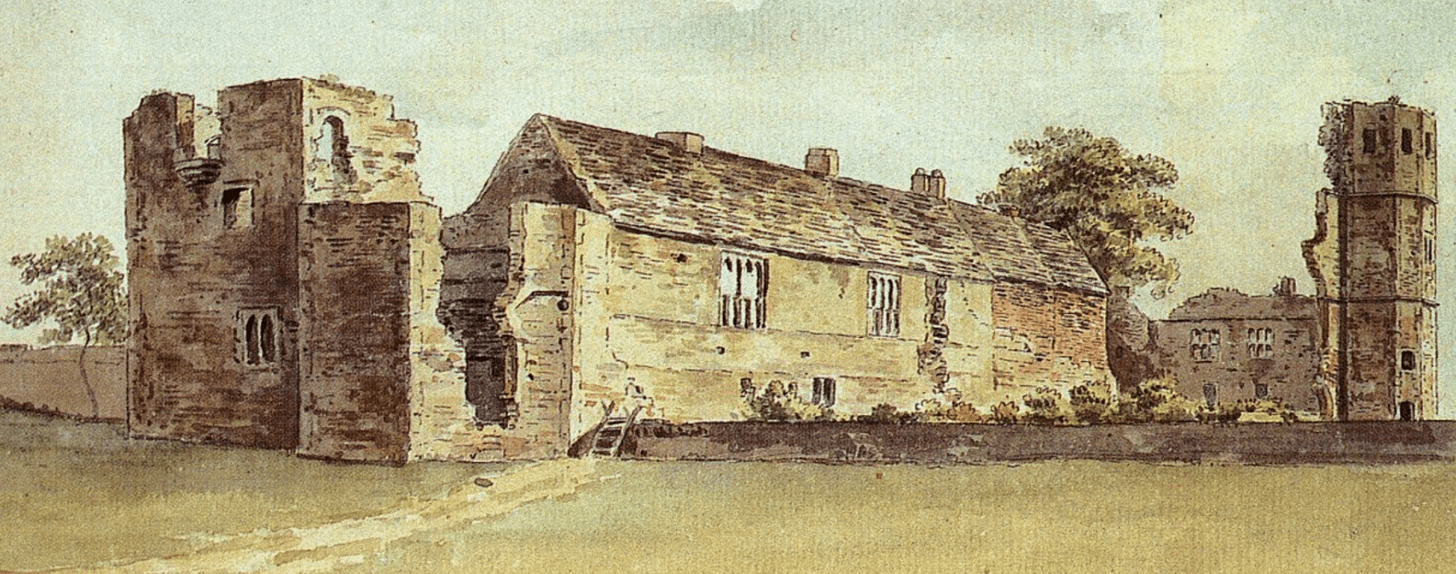

Sheffield’s Manor Lodge is now more famous as the palatial prison of Mary Queen of Scots, who Elizabeth I had imprisoned there for 14 years from 1570. Wolsey’s time there on the other hand has received less attention, but is just as significant. Indeed but for the cardinal’s insistence on continuing his journey to London to clear his name, Wolsey may have even been buried there.

The history of the building stretches back to the 12th century, when a small hunting lodge was built in the middle of a massive deer park owned by the Lords of Hallamshire. The park itself predates the Norman Conquest of 1066 and was one of the largest in England, its 2,500 acres stretching from what is now the city centre to Darnall and Handsworth. The hunting lodge’s lofty position high above the park was chosen for the commanding views it gave over the entire area.

Sheffield in Tudor times was a town of just 1,500 people. The only two stone buildings were the castle and the church with the rest of the houses being made of wood. Many of these so-called ‘hovels’ had cutlery workshops attached and space for livestock. The town stretched from Holly Street in the west to Lady’s Bridge in the east, and West Bar in the north to Fargate and Barker’s Pool in the south. Beyond that it was just fields until you reached even smaller places like Heeley and Beauchief.

Parts of the modern city are still built on the medieval grid system that existed at that time with streets like Figtree Lane near what is now Sheffield Cathedral showing just how narrow thoroughfares were in the 1500s. The streets were just wide enough to get a horse and cart down and featured a gulley which would be used to dispose of rubbish. Four times a year water from Barker’s Pool would be released to flush the gulleys out, the filth accumulating at the bottom of the hill near Lady’s Bridge.

By the time Wolsey arrived in 1530, Manor Lodge had been newly renovated and was one of the two principal residences of George Talbot, the fourth Earl of Shrewsbury. His other — the long-demolished Sheffield Castle — was joined to the lodge at the time by a dense canopy of walnut trees which lined the almost-two mile long avenue connecting them. George Talbot had been asked by Henry to provide lodgings for Wolsey on his journey to London, and the Earl had happily obliged.

The pair already knew each other, both being present at the extraordinary ‘Field of the Cloth of Gold’ meeting in France in June 1520 between Henry and King Francis I, aimed at cementing bonds between England and France and thereby ridding the European continent of war. The spectacular meeting was held over 18 days in a temporary outdoor palace. Expensive cloth and ornaments were everywhere while guests refilled their glasses from wine fountains and two monkeys covered in gold leaf made mischief.

On his arrival in Sheffield, Wolsey was met at the park gates by his host, accompanied by the full coterie of the Earl and his wife’s household. George had received letters from Henry that the cardinal was to be treated not as a prisoner, but ‘as my good lord and the king’s true faithful subject’. The two men reportedly greeted each other as friends, walking arm-in-arm to where Wolsey was to be chambered.

While only ruins of Manor Lodge exist today, George Cavendish’s account describes the cardinal’s lodgings in great detail, allowing us to pinpoint exactly where they were. Cavendish says his master was given ‘a fair chamber at the end of a goodly gallery, within a new tower’, temporarily partitioned off by a ‘traverse of sarcenet’ (a soft silk material). The material had been placed across the middle of the larger chamber so ‘one part was preserved for my lord and the other part for the Earl’, he writes.

The book also recounts how Wolsey and Shrewsbury would meet up every afternoon in the Long Gallery to discuss matters over a glass of wine. The lodge’s gallery had only been completed five years earlier and was believed to be one of the first of its kind outside London.

It is a strange scene. Two noble gentlemen enjoying fine wine in each other’s company while both in the knowledge that one of them was on his way to meet his almost certain death. Events, however, would alter the expected course of history and save Wolsey from a date with the executioner.

One evening, while the cardinal was dining in his chamber with a number of the Earl’s men and chaplains, he took ill. Cavendish, who was ‘dressing the wardens’ (roasted pears) at the time, notes in the text how all the colour suddenly drained from the cardinal’s face. Wolsey told Cavendish that he was ‘suddenly taken about the stomach with a thing that lieth across my breast as cold as a whetstone’. The cardinal diagnosed it as ‘just wind’, but when the symptoms persisted, asked Cavendish to fetch him something that would ‘break wind upward’.

When he returned, Wolsey had not moved, and was clearly in considerable discomfort. A ‘white confection’ had been prepared by Shrewsbury’s apothecary, which Cavendish first sampled in front of his master (presumably to show it was not poison). After taking it ‘wholly altogether at once’, the cardinal immediately ‘broke exceedingly much wind upwards’ before heading off to prayer. Unfortunately for Wolsey, however, his sudden illness was not ‘just wind’ and he was soon taken by a bout of diarrhoea, or ‘lask’ as the Tudors called it.

When it came to illnesses, Tudor England was a dangerous place to live. The infant mortality rate was horrifically high and more than one in ten children died before their first birthday. In the 16th century, even reaching adulthood was considered an achievement and those who lived to 40 were thought to have reached old age. Wolsey’s age in 1530 — which was anywhere between 57 and 60 depending on which date is taken as his true birth year — would have marked him out as a true survivor. But even the most powerful people in the land couldn’t escape the unfavourable odds forever.

To make matters worse for Wolsey, while he was ‘at his stool’, Sir William Kingston had arrived with 24 guards to escort the cardinal to London. Worryingly, Kingston was Constable of the Tower of London, and was under instruction from the king to return him to the capital to ‘try himself and his truth’. While Henry ostensibly still held the cardinal in high regard and had told Shrewsbury that he should be treated with honour, Sir William’s arrival was seen as an ominous sign.

It was decided the journey towards London would continue the next day, but Wolsey was in no fit state to travel anywhere. His diarrhoea continued throughout the night, so much so that by morning he had reportedly had more than 50 stools, leaving him very weak. Tellingly, Cavendish notes that these stools were of a ‘wondrous black’ colour, a symptom which the Tudors called ‘Choler Adustum’.

To modern day medics, a combination of upper gastrointestinal wind and black diarrhoea is a tell-tale sign of only one thing. Nowadays, Wolsey’s death would have been ascribed to prolonged bleeding from either his stomach or duodenum. 21st century doctors have further surmised that this was most likely from a ruptured peptic ulcer or a tear in the lining of the stomach, rejecting out of hand the supposed dysentery infection that was long thought the most likely cause of the cardinal’s death.

Despite his grave illness, Wolsey continued his journey south, first to Kirkby Hardwick Hall in Nottinghamshire and then on to Leicester Abbey. As he left Manor Lodge, he thanked the Earl for his hospitality, but confided to him that he would not reach London alive. When he arrived at Leicester, he is said to have exclaimed: “Father Abbot, I come hither to leave my bones among you.” Two days later he was dead. He is buried in an unmarked grave in the abbey, the precise site of which has never been found.

Further reading: Sheffield Manor: Wolsey and the Spectre of Death, History Extra: Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, The Landmark Trust - Wolsey and Cawood

Visit: Sheffield Manor Lodge

Acknowledgements: The Tribune would like to thank to Sheffield historian David Templeman for contributing original research to this piece.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, we’d love you to spread the word about The Tribune by sending it to your friends. Simply forward this email or click the share button below.

If you have a story you would like us to look into, hit reply to this briefing or email editor@sheffieldtribune.co.uk.

We are looking for talented local journalists who believe in our mission and want to write for The Tribune. If that’s you, please email us at the email address above.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, please join The Tribune’s mailing list to get all our journalism in your inbox.