“Give it a couple of weeks — it’ll be full of spice heads, beer cans and needles.”

That was how one Facebook user, on 30 May this year, greeted the news that Pound’s Park had opened in Sheffield city centre. The park has been built on what used to be the central fire station, and then after that a sad-looking car park. Since then it feels like one disaster after another has visited the city centre: the 2008 financial crisis, the subsequent recession, and the rise of online shopping. Then the pandemic put a nice bow on all of this misfortune. At this point, over a quarter of a century after regenerating this part of the city centre was first talked about, it feels like a bit of a miracle that it’s finally been built at all.

Not that you’d know it from the Facebook user’s reaction. The park, which would probably be better described as a superior children’s playground, isn’t massive but manages to fit a substantial amount into a small area. As well as slides, see-saws and water spouts, there is plenty of seating and flower beds. The consensus seems to be that it’s been a great addition to the city centre, but as anyone who has ever been on The Star’s Facebook page knows, the keyboard warriors of Sheffield are notoriously difficult to please. “A total waste of money,” said one particularly grumpy reader under an innocuous-looking video of families enjoying the park. “It was more useful as a car park,” sneered another.

Pound’s Park sits at the centre of Heart of the City, a new £500 million development funded by Sheffield City Council which has taken the authority five years to build. While it’s still a few months away from being finished, enough progress has now been made to see how the final project will look when completed. As I take a quick tour round the seven-hectare Heart of the City site on Tuesday evening, the setting sun bathes everything it touches in honey. The towers are almost complete while the retail units and heritage buildings are beginning to appear from behind their hoardings.

While construction started in 2018, the seeds of Heart of the City were actually planted in the mid-90s. But there’s been a lot of water under the bridge since then, most recently the pandemic which led to the departure of John Lewis, originally intended to be the scheme’s cornerstone.

But as we approach the end of 2023, and look forward to a year in which an idea that is now over a quarter of a century old finally comes to fruition, is it possible that the delays and setbacks have actually helped Sheffield city steal a march on our competitors? That a city centre based around leisure and the “experience economy” fits with the times better than one based primarily on shopping? Is the astonishingly large amount of money the local authority was required to borrow to fund the project — half a billion pounds — going to pay off for Sheffield long term? Are the perpetually angry cyberwarriors of Facebook going to be forced to eat their words?

The Heart of the City

Nalin Seneviratne had just got back to work after six weeks off sick recovering from back surgery. It was 2017 and Sheffield City Council’s director of city centre development had a problem on his hands. The council had compulsorily purchased a large portion of Sheffield city centre but still didn’t know what they were going to do with it. The developer Hammerson had been asked to deliver an indoor mall, as had been built at Liverpool ONE, but had unexpectedly pulled out to work on a similar project in Leeds. They were back to square one.

As he stood on Cambridge Street, he sketched a rough vision — a new one. Rather than demolish the lot, he would use the street plan that was already there to create a new neighbourhood for the city centre. The idea had a number of advantages. Many of the heritage buildings, or at least their facades, would be left intact. And splitting the development up into multiple discrete blocks meant they could each be done separately, thereby reducing the overall risk. That sketch he made back in 2017 was the birth of Heart of the City we see today.

The decision that Sheffield ultimately came to happened as much by chance as it did by design. In the 2000s and early 2010s, most UK cities were following the Liverpool model and trying to regenerate their city centres through retail. “It’s not that other cities were doing the wrong thing; that’s just how things worked back then,” Seneviratne tells me. However, as a result of his esoteric vision, Sheffield ended up following a different path.

Doing it this way certainly hasn’t been easy or cheap. Dispensing with the idea of a brand new shopping centre allowed them to maintain the area’s historic street plan, but meant they needed to build half a dozen separate buildings, which costs more money. The three main new office buildings Grosvenor House, the Isaacs Building and Elshaw House have added over 250,000 sq ft of office space to the city centre (including, in Elshaw House, Sheffield’s first zero carbon-ready office building, which will be the new home of law firm DLA Piper).

The heritage buildings they have preserved have given the development more authenticity and a link with Sheffield’s industrial history. However, preserving the Victorian facades on the new Radisson Blu hotel (as well as the famous Pepper Pot and Laycock House buildings) on Pinstone Street added substantial cost to the project while each time they wanted to adapt one of the listed buildings on Cambridge Street meant even more negotiations with Historic England.

And in the original plans, Pound’s Park itself was meant to be a multi-storey car park but was changed to provide much-needed green space in Sheffield city centre and act as a focal point for the development. Seneviratne believes that these decisions, while difficult and costly, are now finally paying off. “These are all very expensive and tricky things to do,” he says. “But at the end of the day only somebody like the council can do them because they can take that long term view on the investment in the city centre.”

Seneviratne left the council to set up his own consultancy in 2021, although he has since done work for Queensberry, the council’s strategic development partner on the scheme. Is he confident it will all be filled? In a word, ‘yes’, but he says it may take some time until people see that. The big units: Grosvenor House, the Isaacs Building and the largest Pinstone Street building have already been filled with major anchor tenants like HSBC, Henry Boot, the law firm CMS and the Radisson Blu hotel. The ground floor units may take a bit longer to fill up, but he’s confident it will happen. “It won't take place overnight and there will be a bit of vacancy there,” he tells me. “But my view is, be patient.”

Half a billion pounds is a lot of money for a local authority to borrow, a loan which was secured against the extra business rates the development will bring in. This means the authority will be paying for Heart of the City until the 2060s. However, Seneviratne believes it will ultimately come to be seen as a far-sighted decision. “We’ve got a fantastic piece of city centre architecture, design and use — there's something there for everybody to enjoy.”

‘Knowing what we know, it is genuinely exciting’

Of all the developments in Heart of the City, James O’Hara and Tom Wolfenden’s Leah’s Yard project is one of the most prestigious. The Grade II-listed building on Cambridge Street is a Sheffield heritage gem — one of the former ‘little mesters’ workshops which so epitomise the industrial heritage of the city. There were once dozens of these workshops scattered across Sheffield, filled with small traders making knives, tools, cutlery and scissors. Most have now disappeared, but as a result of Heart of the City, this one will be given new life.

The pair won the contract to run the building from the council back in 2020. But while Leah’s Yard will operate as a business and make money from renting their space out to tenants, it wouldn’t have made sense as a purely commercial venture. “No big developer looking to make a quick return is going to take on what is a really weird, idiosyncratic building,” says O’Hara. “What the council have done is say that instead of letting a Grade II-listed building rot, we’ll take a longer term view because we think it’s important for the city centre.”

When it’s completed next spring, over a year later than originally planned, Leah’s Yard will consist of retail units on the bottom floor and studios on floors two and three. In terms of which type of businesses will fill the upper floors, the tenants will be a modern take on what a ‘maker’ is in 2024. While in the past, ‘little mesters’ included people making bone handles for knives or buffing cutlery, now it might be someone making podcasts or having a photography studio.

They have had no shortage of interest. When they advertised the 13 tiny units in Leah’s Yard, they got 153 enquiries from independent businesses all over the city. Having worried about not getting enough applications to fill the building, now they have the opposite problem. “It will be sad to say no to people,” O’Hara says.

As we’ve reported before, James O’Hara says Cambridge Street will be “one of the best streets in any city centre in the country” and insists: “You can hold me to that”. He jokes about his words making him hostage to fortune, but doesn't take them back. As well as Leah’s Yard, the music venue in the former Bethel Chapel next door finally has a tenant although they can’t tell me who yet. And further down will be the Cambridge Street Collective (in the building that readers of a certain vintage will remember as Henry’s Bar), a new food hall operated by the people behind Cutlery Works which may include JÖRO, one of Sheffield’s best-reviewed restaurants.

“Cambridge Street will be a brilliant example of what a city centre street can be,” O’Hara says. He believes that the mix of businesses and bold architecture like the rusted steel of the Cambridge Street Collective roof will complement the authenticity of the historic listed buildings and make the street a real destination. “And there won’t be a chain in the entire thing.”

The pair have been spending a lot of time in Halifax to see what that town has done with its Piece Hall. Once a decaying and expensive millstone around the neck of the local council, the Grade I-listed Georgian masterpiece was saved from demolition and now attracts people from all over the world to the small West Yorkshire town. “People now go to Halifax for weekends,” says Wolfenden. “One great project can really transform a town.”

Outside The Pearl, O’Hara’s latest business venture at Park Hill flats, the pair occasionally shoot each other glances wondering how much they can tell me. In the end, as they get ready to head off to Manchester to entice another prospective tenant across the Pennines, Wolfenden opts for vague but intriguing confidence: “Knowing what we know, it is genuinely exciting.”

‘In which other city in the world could you do that?’

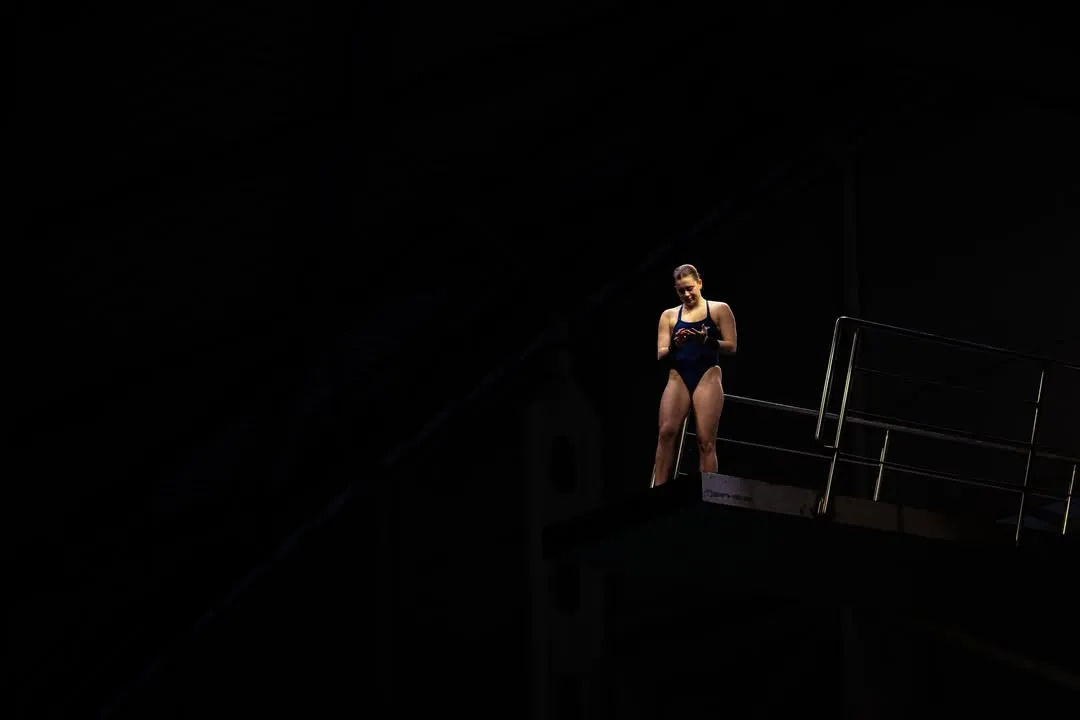

Bridget Ingle and her husband Paul are sitting on the balcony of their apartment on the top floor of Burgess House, one of Heart of the City’s two main residential developments. Below us is Five Ways, the pedestrianised junction which forms the focal point for several of Heart of the City’s main buildings. From our vantage point looking east down Charles Street we can see the greenery of Norfolk Heritage Park while looking west down Wellington Street in the far distance we can see the Peak District hills overlooking Hathersage. “In which other city centre in the world could you do that?” asks Bridget.

The couple have been living in Burgess House now for just over a year, having moved there in August 2022 when the entire area was, in Bridget’s words, “a building site”. The block has 52 flats, none of which can be sublet or used as Airbnbs — they have to be lived in by those who buy them as part of the council’s vision of creating a stable, long-term community there.

They took the decision to move here after their children grew up and they wanted to downsize. Paul took the most convincing that moving to the city centre was a good idea. “Our friends were horrified,” Bridget tells me. “As you get older, people assume you will want to move to the country and have a more sedate lifestyle, but I want to make sure things like shops, public transport, the art gallery and library are on my doorstep.”

Have they encountered any problems? The delays were frustrating, they tell me, with Burgess House opening almost a full year after it was meant to in October 2021. But other than that, they seem very happy to be city centre living pioneers. It’s not particularly noisy but it’s doubtful they would notice even if it was — the apartments in Burgess House have triple-glazed windows. Bridget also says the city centre’s growing number of green spaces means she doesn’t miss her garden and that other perennial bugbear of city centre living — people nosying in your flats — isn’t something that concerns them either. “If you don’t want to be overlooked then don’t live in a block in the city centre,” she says.

At the end of our conversation Bridget tells me she thinks Sheffield City Council deserve more credit for Heart of the City. When the original proposals for a mini-mall were shelved, many were relieved that a plan that would have meant widespread demolition of valuable historic buildings had fallen through. What has resulted, she argues, is something that represents Sheffield’s unique heritage better than a soulless and identikit shopping mall. “This is more interesting, more creative and more quirky,” Bridget tells me. “It’s more in keeping with the kind of city Sheffield is.”

Paul agrees that having more people living in the city centre like they do in other European cities was a good strategic choice for the city council to make. “It will mean more cafes, bars and restaurants will open here,” he tells me. “It’ll help bring life back to the city centre.”

The city centre of the future

I can see how all this could appear slightly panglossian. The city centre does have problems, and those problems aren’t all going to be solved by Heart of the City. A recent Freedom of Information request lodged by my colleague Victoria Munro found that the S1 postcode alone currently had 752 empty units with a total rateable value (an assessment of what the property would rent for if it were available to let on the open market) of more than £11 million. Venturing out of the shiny new Heart of the City complex quickly brings you into contact with bits of the city centre that look less good. Opposite Burgess House is the festering sore on the city centre’s reputation that is the decaying Salvation Army Citadel (James O’Hara tells me he reckons it would cost at least £5 million to fix it up into a usable state again). And facing Laycock House at the bottom of Charles Street, the dated and soon-to-be-demolished Midcity House makes it look like the Soviet Union did actually drop an atomic bomb on The Moor back in 1984 after all.

But Sheffield city centre is changing, and Heart of the City is the biggest and most prominent example of that change. As my colleague Daniel Timms wrote in his recent excellent piece on Meadowhall, newly restored public spaces like Fitzalan Square and Orchard Square provide a glimpse of what Sheffield city centre could be in the future. Bringing people in to work, to play, to eat and drink — and yes, still to shop — is the theory behind Heart of the City. You don’t have to spend money to come to Pound’s Park, but the idea is that people will come there with their children and then get something to eat or drink in one of the cafes nearby. That the new office units will provide a fresh source of footfall to local food and beverage businesses still struggling with the decline of city centre shops.

Ultimately Sheffield’s half-luck, half-judgement decision was a bet, and some bets pay off while others don’t. But in-person retail isn’t coming back any time soon, and the so-called “experience economy” isn’t going anywhere. In the past, people came into the city centre for everything; reams of A4 paper, pairs of scissors, batteries. Now, many (maybe most) people order these things online and city centres have to adapt to this new world.

On Facebook, the keyboard warriors later turned their attention to a climbing boulder at Pound’s Park. Rather than providing a fun distraction for children of all ages, one person reckons it’s more likely to cause a rush of broken bones at Sheffield Children’s Hospital. There are always going to be grumpy people, but I think Heart of the City is something that Sheffield should be really proud of.

So, am I being too positive about Heart of the City? Or is my optimism justified? Please let us know in the comments section below.