Good morning readers — and welcome to our first ever Thursday newsletter. We’ve had an amazing reaction to our membership launch this week, and we’re just two days in. It’s great that so many of you want to get all our newsletters from next week and support our vision for a new journalism in Sheffield — huge thanks to our first Tribune members. Our first members-only newsletters will start next week.

If you haven’t joined yet, there is still time to take advantage of our 10% launch-week discount. It means a Tribune membership costs £6.30 a month, or just £5.25 a month if you pay for a year (£63).

Starting next week, more than half of what we write will go out in members-only emails, so if you want to avoid missing out on some of our best interviews, long reads, political reporting, reading tips, cultural recommendations and much more, join us as a member today for the price of a couple of pints a month.

We’re right at the beginning of our journey here, and it’s so vital for us that anyone who likes the kind of journalism we publish (and wants more of it) signs up. The more members we get, the closer we will get to financial sustainability, and the more great local journalists we can commission in the months ahead. Once we clear a certain number of members, we can start thinking about adding another reporter to the team. And that’s how The Tribune will grow — organically and funded by you, our readers.

Today’s story is about painter John Hoyland. Born in Totley in 1934, Hoyland went on to become one of the most celebrated abstract artists of the 20th century. A new exhibition of his final paintings has just opened at the Millennium Gallery.

As well as our Hoyland story, we have a mini-briefing of stories you might like to read and things you might like to do in Sheffield over the next few days. All our members-only newsletters (which start next week) will have a useful mini-briefing followed by an in-depth main story, whether that’s a long read, an interview, a piece of data analysis or a historical feature.

Mini-briefing

Make sure you read this great piece written by Now Then editor Sam Walby about political wranglings over the future of the former Castle Market site. The story examines the current row over Councillor Mazher Iqbal’s involvement in development plans. But it also looks at the multiple competing visions that have been put forward for the site since 2013.

Sky News reported yesterday that Sheffield Forgemasters, one of the last remaining steelworks in the city, could be taken into public ownership ‘within days’. A deal for the Ministry of Defence to buy the firm, which makes parts for the UK’s nuclear submarines, has been under discussion for six months. The MoD said there were in ‘regular dialogue’ with the company.

The Sheffield Adventure Film Festival takes place this weekend, showcasing 100 of the best new adventure, travel and extreme sports films, some of which will be shown at the Peace Gardens. On Saturday and Sunday, the Cliffhanger climbing event is also taking place across the city centre and the British Bouldering Championships is being held on Devonshire Green.

There will be some sore heads in Sheffield today after England’s Euro 2020 semi-final win against Denmark last night. Fans partied into the night on West Street and Ecclesall Road, but Sharrow-born defender Kyle Walker — who put in a magnificent performance — wasn’t getting too carried away. The final between England and Italy will take place on Sunday night at 8pm.

Book of the week

After we published our brilliant recent piece about Ethel Haythornthwaite, one of our readers suggested this book to us. Written by local author David Price in 2011, Sheffield Troublemakers: Rebels and Radicals in Sheffield History features a chapter on Ethel herself, as well as a host of other Sheffielders who have proved a thorn in the side of the powerful over the years.

The book features Joseph Gales, the owner of the Sheffield Register (the city’s first newspaper, established in 1787) and John Ruskin, the art historian who set up a communist farm in Totley. It also include gay rights campaigner Edward Carpenter and the leader of the ‘Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire’, David Blunkett. The only thing it’s missing is an updated chapter on the tree protesters.

Buy Sheffield Troublemakers: Rebels and Radicals in Sheffield History here.

“Collaborating with chaos”: The rebellious art of John Hoyland

By Dan Hayes

John Hoyland almost failed his art school diploma. After spending four years at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London, for his final show he made a bold decision. He had great talent but was bored with figurative art and landscape painting. The new art that was coming out of the United States inspired him. Not wanting to be limited by the traditional art school rules and strictures, everything he hung in his final show was abstract.

It wasn’t well received. Sir Charles Wheeler, the President of the Royal Academy, was so appalled he ordered Hoyland’s pieces to be taken down from the walls of the diploma galleries. It looked like all his hard work was to be for nothing. But his teachers tried to talk Wheeler round. They showed him the young artist’s landscapes and representational pictures in the hope of proving his talent. It worked, and Hoyland passed.

Much later in life — after the precocious 26-year-old from Sheffield had become John Hoyland RA, one of the “grand old men” of British art — he would push back against the “abstract” label. But as a younger artist he found throwing off the shackles of traditional painting incredibly freeing. “It's a bit like when music moves you and you don't know why,” says Wiz Patterson-Kelly, one of the curators of a new exhibition of some of his final paintings at the Millennium Gallery.

“You don't need the description to hear a piece of music, it moves you and makes you feel emotion,” she says. “That's kind of what he was going for in his work through colour and form. He really felt like you didn't have to know anything about a painting. You didn't have to have it explained to you. It was a thing in itself. You saw it and felt moved by it.”

Hoyland had graduated to the Royal Academy Schools from Sheffield College of Art in 1956. Born into a working class Sheffield family, he was brought up on Mickley Lane in Totley. His dad worked as a tailor while his mother stayed at home, but John’s aptitude for art showed itself early on. Picking up on her son’s talent, his mother would encourage him by letting him stay up late — but only if he was drawing.

The career choices open for a young man in Sheffield at that time were limited. John didn't have any interest in working in steel, coal or manufacturing — although to him it must almost have felt like an inevitability. But Patterson-Kelly says he was “really looked after” by some of his tutors at Sheffield Art College who recognised and nurtured his talent. “They said you can go out there and do more than this,” she says. “They told him to go for it.”

In the 1950s, traditional landscape and figurative painting was all that was taught in British art schools. But after travelling to London to see exhibitions at the Tate by people like Mark Rothko and Nicolas de Staël, John came back inspired. The huge fields of colour which these new painters were using were like nothing he had ever seen before. On his return he began working on abstract works of his own.

Hoyland managed to get some scholarships and awards which allowed him to see a bit of the world beyond Sheffield. These first trips were “massively formative” for him, says Patterson-Kelly, and led to a lifelong love of travel, which in turn inspired his work. “He got really fired up by it,” she says. “It helped him see the possibilities of getting out there into the world and doing something else.”

Wiz now works for the Hoyland Studio in London, but first met the artist through her work with the legendary British abstract sculptor Anthony Caro. Since Hoyland’s death in 2011, she has been working to catalogue his entire body of work, a task that has kept her and her team busy through the repeated lockdowns and delays of the last 18 months.

Hoyland and Caro were great — if unlikely — friends. John was from working class Sheffield and Caro had been educated at the Surrey public school Charterhouse. But the pair had worked together on the Sao Paulo Biennale in 1969 and “just hit it off”. Wiz says John could be “a bit terrifying” when she first met him but also remembers his fantastic sense of humour. “He didn't take any prisoners but even when he was sick towards the end of his life he always entertained everybody and was really generous in his spirit,” she says. “He was a big character.”

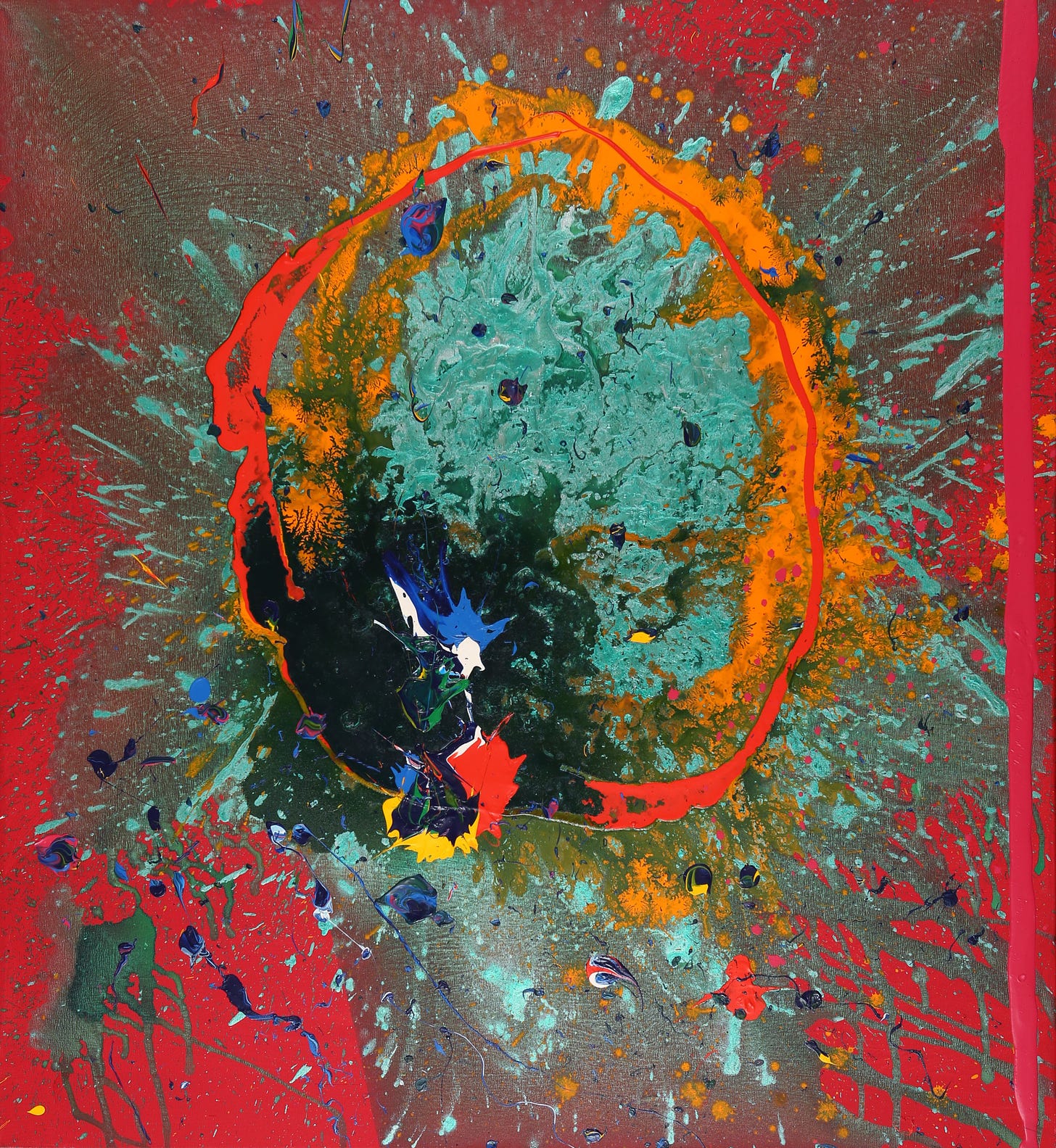

While John always had an idea of the kind of work he wanted to do in his head, Patterson-Kelly says he also believed paintings almost “made themselves”. “He would sometimes sneak up on a piece and try new things,” she says. “He would put it on the floor, move the paint around on the canvas and wait for it to dry before picking it up again and carrying on working.” An art critic once wrote that seeing Hoyland work was like watching someone in ‘collaboration with chaos’.

The only footage of his creative process which still exists is on a BBC programme from the late 1970s called Six Days in September. In it the then 45-year-old artist says when he “gets into trouble” with a painting, he sometimes tries to “think his way out of it.” “But I don’t know whether that’s the best answer really,” he says, while daubing a huge canvas with a vibrant splodge of paint. “Sometimes one has to try to unlearn what one’s learnt...and try to get back to a more simple state. A more childlike use of colour.”

The work currently being exhibited at the Millennium Gallery all comes from the last eight years of his life. He lost several close friends in this period, including fellow artist Patrick Caulfield. He also became ill himself, undergoing major heart surgery two years before he died. These experiences saw his paintings become much more concerned with existence and mortality. He also began to look for inspiration from the cosmos, what Wiz calls the “big things that go on forever.”

There are only nine pieces in the show, including two huge canvases, several medium sized pieces and a few smaller works. “A lot of those paintings are really reflective,” she says. “They're sort of visceral but they're not melancholic, they're really vibrant and they celebrate life. He loved life and loved the world and could see everything continuing. He had a real joy in that so they’re celebrations. More than anything I would say it's a great legacy for him to leave behind some work that's so positive and energetic.”

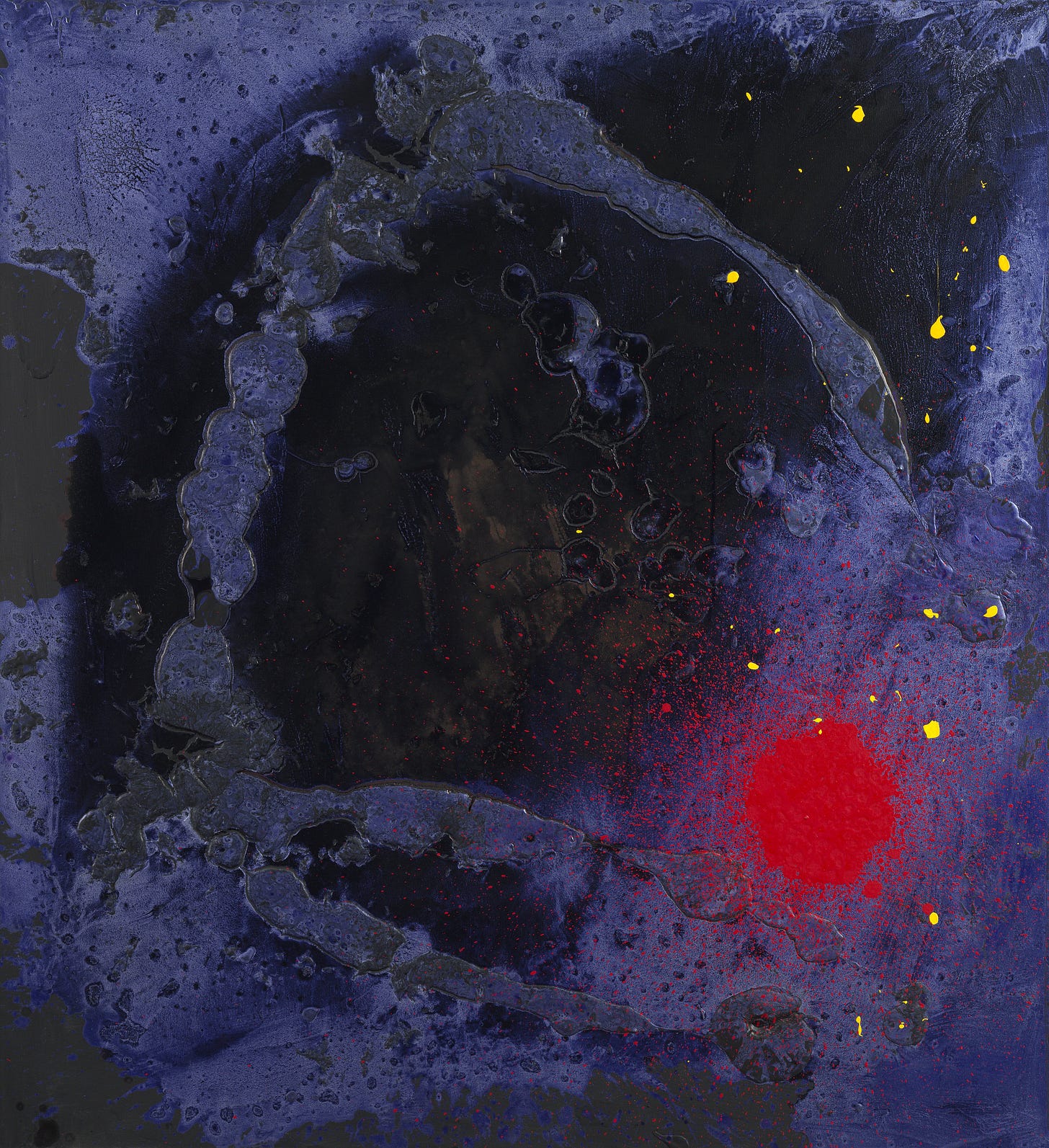

When I saw the huge canvases up close this week at the Millennium Gallery, it rendered even the highest-resolution photograph of them hopelessly inadequate. Bold matte features in the foreground battle with iridescent backgrounds which continually change in the light as you move around them. As Patterson-Kelly says, some evoke astronomical features like black holes. Others look like the landscapes of strange new worlds as seen from above; a drone’s eye view of an undiscovered country.

His final painting, completed four months before he died in 2011, is entitled Moon in the Water (Mysteries). An astonishing contrast of deep purples and brilliant red, it is defiantly not the work of someone who is content with fading away in the last months of his life. The painting’s title is taken from a poem by 19th century Japanese Zen master Gisan, which was translated in a book Hoyland owned.

Coming and going, life and death:

A thousand hamlets, a million houses.

Don't you get the point?

Moon in the water, blossom in the sky.

Speaking before the exhibition was installed, Wiz said she was looking forward to hanging the work, but admitted the process would be bittersweet. “It is such a sadness that John is not here to see it in his hometown,” she says. “He still has family there and it’s a place that was very dear to him. But it’s a fantastic culmination of all these years' work and we get to take a really nice slice of what John did in his final decade and present it back to Sheffield.”

John Hoyland: The Last Paintings at the Millennium Gallery runs until 10 October.

Go deeper: A book to go with the exhibition, John Hoyland: The Last Paintings, including essays by Natalie Adamson, David Anfam, Matthew Collings and Mel Gooding, with a preface and biography by Sam Cornish, is out now. Order online here.

We hope you enjoyed our first Thursday newsletter. Normally this one would be members only but for one week only we are sending all our newsletters out for free. If you want to carry on receiving our members only emails next week, subscribe using the button below.