Good afternoon members — and welcome to Thursday’s Tribune.

I’ve never really understood the pull of gambling. I’ve had many friends who have enjoyed going to casinos and some who have even travelled half way around the world to gamble in places like Las Vegas — but I’ve never really got the buzz. For most people it’s just a harmless bit of fun that ends when the night or holiday does — or you reach your limit. But for other people it can be much more dangerous. Today’s story is about a young Sheffield teacher who took his own life in 2017 after being unable to escape his addiction. A new book about gambling by Guardian journalist Rob Davies looks at how the industry can ruin lives.

News round-up

🎸 Organisers at Sheffield’s free Peace in the Park music festival are appealing for donations after it was revealed that they have a budget shortfall of £1,200 for this year’s event. The music festival usually takes place on the Ponderosa in Upperthorpe every June but has been absent for two years due to the pandemic. They have been unable to carry out as much fundraising as they would do normally over the last few years due to coronavirus. To contribute click here.

🥗 A nice piece in Now Then about innovative Sheffield social enterprise Food Works which in 2021 turned 500 tonnes of produce destined for landfills into nutritious and delicious food and drink to sell at their three volunteer-run cafés in the city. As well as the cafes, Food Works also runs a farm where volunteers grow fresh produce for distribution and during the pandemic sold frozen meals for people to eat at home. All food is sold on a “pay what you can” basis with a minimum £1 contribution.

🏗 A great piece in The Guardian about Park Hill flats looks at the estate’s long history from postwar utopia to its current “contentious regeneration”. Reporter Oliver Wainwright speaks to long-time resident Joanne Marsden (who we spoke to for our piece about Park Hill last year) and Urban Splash’s Tom Bloxham who tells him that while the gaudy colours of the huge regeneration project’s first phase were needed to “make a statement”, the next phase has been designed to be much more subtle.

Worth a look

🎻 The BBC Philharmonic returns to Sheffield City Hall on Friday to play three pieces by Elgar, Ravel and Vaughan Williams. Conductor John Wilson will open the concert with Edward Elgar’s Cockaigne Overture before continuing their season-long celebration of the 150th anniversary of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s birth with a performance of his “London” Symphony, one of the composer’s most evocative and atmospheric creations. Tickets are £18 (under 12s go free).

🍔 The first-ever Quayside market takes place at Victoria Quays this Saturday (April 9). The market (which organisers hope will be a monthly event) runs from noon to 9pm and will include street food, craft beer, cocktails, music, art and family-friendly activities. The market is the brainchild of local businessman Bally Johal who runs the True Loves bar on Victoria Quays. He says he hopes the event will help to put the beautiful canal basin area in the spotlight.

🎭 Comedian Eddie Izzard comes to Sheffield this weekend to play two nights in aid of under threat music venue The Leadmill. The first on Saturday (a version of his latest show Wunderbar) is already sold out — barring returns. But the second on Sunday afternoon (a comic retelling of Charles Dickens’ classic novel Great Expectations) still has availability. Both shows are in support of the much-loved venue’s #WeCantLoseLeadmill campaign.

How gambling claimed the lives of two young Sheffield men

Jack Ritchie was still at school when he started gambling. He was a 17-year-old student at Tapton School in Crosspool and would visit a bookie’s in Broomhill on his lunch breaks. At first it was just a social thing — something he would do with friends. But a big early win changed his relationship with the so-called fixed-odds betting terminals (FOBTs) that became popular in betting shops during the 2000s.

His friends would eventually drift away from gambling but Jack stayed, racking up bigger and bigger debts. At one point he had to get bailed out by his parents after he lost £5,000 that had been given to him by his grandmother. Realising his son had a problem, Jack’s dad Charles took him around every Sheffield bookie’s they could find, signing up to “self-exclusion” schemes to voluntarily bar himself from entering betting shops. But if that was a solution that worked for previous generations of gamblers, it certainly doesn’t work any more. His parents, who live in Nether Edge, later found out his gambling had continued almost immediately online — and he carried on when he went to university in Hull. Jack gambled away his student loan within the first term of his degree but after that kept his losses low enough that his parents didn’t notice.

It was when he moved back to Sheffield — when he had a job, a flat and access to credit cards and bank loans — that Jack’s gambling entered a more serious, darker phase. It was becoming clear to his parents that gambling was something that was sucking him in like a force field. Gambling addiction doesn’t involve substances, but for addicts it seems to erode their willpower in the same way as drugs and alcohol, cruelly mocking their conviction that they can control their own destiny.

During one binge in 2015, he lost £8,000 in a matter of weeks, including £5,000 in just a couple of days. In need of direction, he went on a volunteering trip to Kenya, far enough from temptation to feel free of his addiction. After he came back, he travelled to Vietnam to teach English, and seemed to be enjoying himself.

After just three months in Hanoi he contacted his parents to say he’d started gambling again. They offered to cover his losses and pay for his flight home — and Jack said he’d think about it. But just three days later, he emailed them a suicide note and posted some pictures of himself to Facebook. He then left his drink on the table, climbed to the top of the six-storey building he was in, and threw himself off. “I’m past the point of controlling myself,” he wrote in the note. “I’m not coming back from this one.”

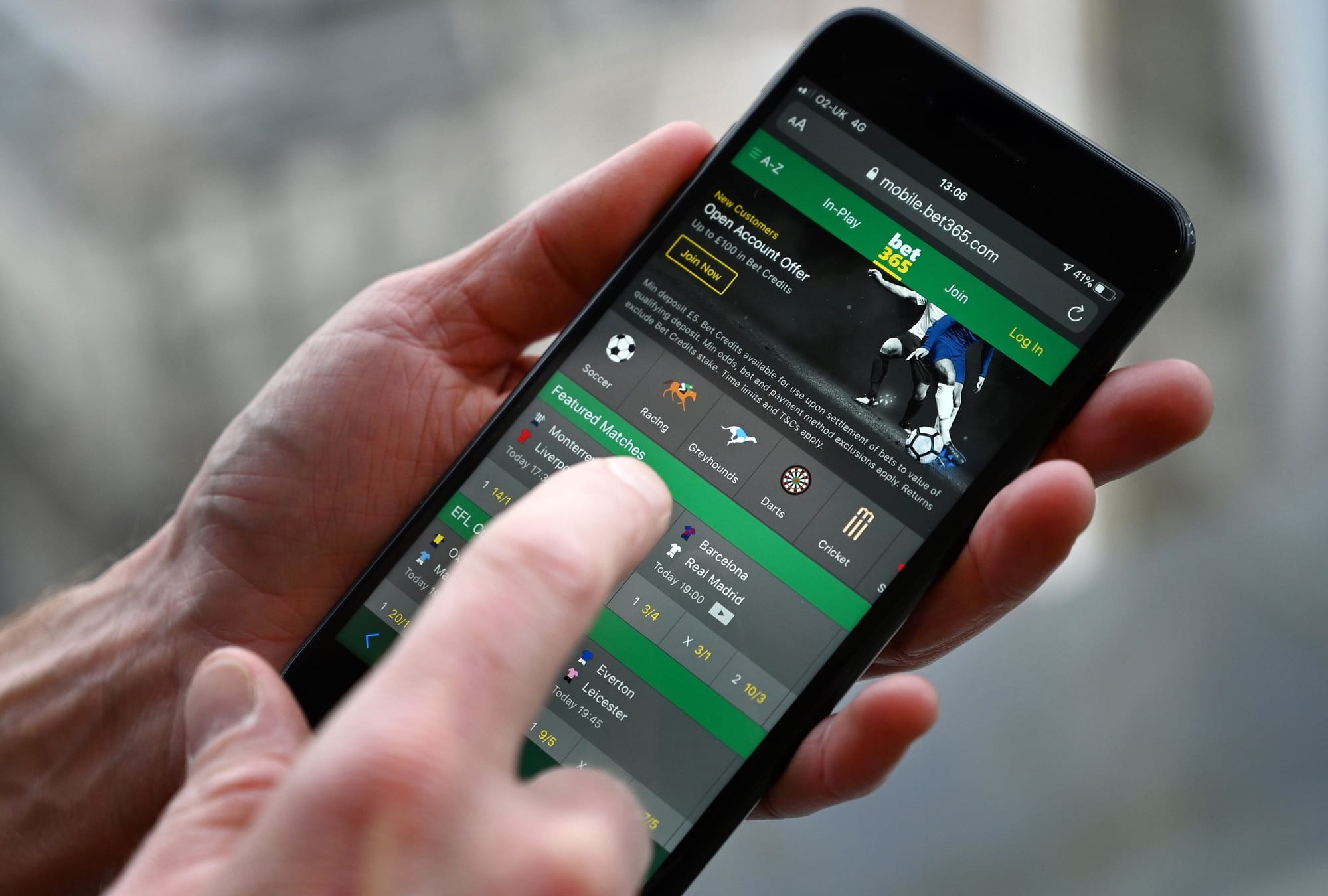

Jack’s story is recounted in a new book about gambling by the Guardian journalist Rob Davies. Jackpot: How Gambling Conquered Britain looks at how the industry has grown over the last 20 years, from a pastime that was limited to bookmaker’s shops and tightly controlled by legislation to an activity that is now ubiquitous. Seemingly everywhere you look you are bombarded by advertisements to bet, from football shirts to television and social media to sports competitions.

According to the Gambling Commission, there are currently 430,000 gambling addicts in the UK, including 55,000 aged 11-16 — with two million more said to be “at-risk”. Of these, between 250 and 650 people die by suicide every year as a result of gambling addiction. If you exclude the National Lottery, the UK gambling industry takes around £11bn a year from punters. That would mean more than £200 per adult if everyone gambled, but of course they don’t. It’s clear that a large number of people who gamble — and not just addicts — are losing thousands of pounds every year to the bookmakers.

The liberalisation of the industry by the Blair government in the early 2000s led to a huge increase in advertising. When the Gambling Act came into force in 2005, there were around 90,000 TV “spots” that promoted gambling of some sort. Just six years later that had increased tenfold to 955,000 and would go on to reach 1.4 million a year later in 2012. If you take out lotteries (which were allowed to advertise before deregulation) the number of gambling adverts increased by a factor of thirty-seven in just seven years. As Davies notes in his book, the effects that this might have on impressionable young people is largely unknown:

By charting the rise of gambling advertising, it’s possible to show how we have, in little over a decade, built a world in which it is virtually impossible to escape online casinos and bookmakers. This is a cultural sea change, fuelled by liberal regulation and technology, the effects of which are largely unknown. How will today’s young adults, who’ve grown up in a society drenched in the language, imagery and culture of gambling, fuelled by technology that didn’t exist when their parents were growing up, deal with an immersion they’ve learned to accept as normal?

Davies first met Jack’s parents Liz and Charles in 2017, shortly after their son had died. Since then they have become leading advocates for reform in the industry, helping set up Gambling With Lives, a charity that both supports families who have been bereaved by gambling-related suicides and raises awareness of the problem. Jack's story is well-known thanks to them, but most cases never make the headlines. “It’s hard to quantify exactly how many there are because most people don’t want to talk to the press about horrendous things like this that happen to them,” Rob told me when we spoke earlier this week.

Another case that we do know about involved 25-year-old engineer Chris Bruney, from Aston. He took his own life in April 2017 — just seven months before Jack Ritchie — after losing £119,000 in just five days with online betting site Winner.co.uk. His case shone a spotlight on so-called “VIP status” within the gambling industry — schemes set up by gambling firms to offer rewards and bonuses to “high-value customers” (meaning gamblers who lose a lot of money). The government last year announced its intention to ban the schemes as part of the Gambling Act Review that is now expected in May.

The big gambling firms are incredibly profitable companies and powerful actors in society. They have sophisticated lobbying operations and spend a lot of money wining and dining MPs, who they hope will then speak in favour of the industry. There are MPs who work for gambling companies as second jobs and those same companies hold regular meetings with ministers.

Davies says he gets a lot of pushback, particularly on social media, from people who think that people like him are just “nanny statists” who want to stop people having fun. “But that’s not how I’ve ever approached this,” he tells me. “I don’t think the industry should be banned, I just think there is behaviour at the fringes of the industry that has been allowed to run completely out of control.”

Much now rests on the long-awaited review of the Gambling Act 2005 that is now expected next month. Regulating advertising is widely expected to be a major part of the review, as is a ban on VIP schemes of the kind that were so harmful to Chris Bruney. Beyond this, Davies argues that affordability checks should be integrated into online gambling games and that the Gambling Commission should be empowered to crack down harder on firms that engage in harmful practices with bigger fines and licence suspensions.

Davies’ book also examines what it is that makes gambling so dangerous for some people. He’s wary of making comparisons with other addictions and accepts that in some respects physical addictions are far worse. But he says there are ways in which gambling addiction is unique that are not well understood.

One of these is gamblers never have to stop. If you drink a lot or take a lot of drugs at some point your body will shut down: you’ll pass out or you won’t be able to have any more. But with gambling as long as you can find money from somewhere, you can keep going. So people will beg, borrow and steal to keep doing it. Betting companies understand this and tweak their games to make them more appealing in a way that with drugs and alcohol is more difficult.

One example of this is so-called “disguised losses” where gamblers are told they have “won” 50p from a £1 stake to trick them into believing they aren’t hemorrhaging money. Some games like FOBTs are even designed so it’s easy to win a small amount on each spin and the machines reinforce the trick further by playing music and flashing in the same way they do for a win as they do for a disguised loss.

Gambling addiction can also be more easily hidden. Drug or alcohol abuse is written on the body, whether it’s the immediate intoxication or the long-term effects. But you can be sitting on the sofa next to your partner gambling away your mortgage money or your children’s university fund without them knowing. Davies tells me he has spoken to people who have recounted sneaking off to the loo to check their phone during their child’s birthday party because they wanted to see whether their bet on a Venezuelan under-23 football match had paid off. Inevitably, it probably had not.

A decade ago, betting on football wasn’t the huge money-spinner it is now. You could bet on the result of the match, the first scorer and not much else. But stock-based gambling giant Bet365’s invention of so-called “in play” betting changed that. You can now bet on the scorer of the next goal, the next corner, the halftime score and so on. This means the opportunities to bet throughout the game are much greater (as are the revenues for the gambling companies, with the amount staked by punters on football roughly doubling over the past six years). This rapid-fire element presents a new danger for people who have addictions, particularly when combined with slick TV adverts which tell punters “it matters more when there’s money on it”.

Davies says gambling’s worst effects are often found in low-income communities. Part of that is because less well-off people can sometimes be tempted to look for “get rich quick schemes” — a roll of the dice that could change your life or at least improve your circumstances for that week. “Unless you’re very wealthy, gambling addiction is almost always going to lead to financial ruin,” he says. “You can get high functioning alcoholics or drug addicts. Gambling inevitably completely alters your life and therefore the lives of everyone around you because of the financial aspect.”

At the recent inquest at Sheffield Town Hall, Liz and Charles Ritchie were hoping that Coroner David Urperth would find the state’s liberalisation of gambling laws in the early 2000s had caused their son’s suicide. This didn’t happen but the inquest did conclude that the “warnings, information and treatment” for problem gamblers at the time of Jack’s death were “woefully inadequate and failed to meet [his] needs”. He added the situation had since improved but there was still “significantly more” that needed to be done and that he would be writing to government departments and gambling agencies with warnings about how future deaths could be prevented.

Davies is keen to pay tribute to the couple who have thrown their energies into campaigning after suffering unimaginable loss. He has got to know them well over the last five years and says his book simply wouldn't have been possible without their help and support. “They are people who I admire greatly,” he tells me. “They have gone from these people who suffered pretty much the worst things that can happen to anybody and then channelled all of that into this extraordinary campaigning work.” As well as his young son Sacha, Rob Davies’ book is also dedicated to Jack Ritchie.

Jackpot: How Gambling Conquered Britain by Rob Davies is out now, priced £14.99.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.