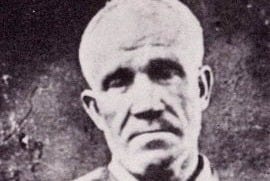

Of all the various rogues and ne’er-do-wells who populate Sheffield’s criminal history, none has ever quite matched the dizzy achievements of Charles Peace in Victorian England. Charlie — as some call him — grew up in and around the city. He became a master of disguise, an elusive cat burglar and some claim he provided Sir Arthur Conan Doyle with material for Sherlock Holmes’ arch-nemesis, Moriarty — and indeed, on reading writer Nicholas Booth’s account of Charles Peace, this seems more than plausible.

His exploits are all the more astonishing for his many years on the run despite a nationwide manhunt. If the story begins here, it also ends in Yorkshire on a freezing cold morning in February 1879, 25 years after his first recorded case that started him on his extraordinary life of crime.

The short and wizened old man (“a little stubby towards his forehead”, in one account) who slowly made his way to the gallows that bitterly cold February morning in 1879 was resigned to his fate. He looked much older than his late forties, the cares and sorrows of this world following him into the next. His face, already pale and haggard, “changed colour”, a contemporary witness noted, “and there was a startled look in his eyes.”

But within moments, Charlie Peace had collected his composure. He walked in step with the governor of Armley Gaol in Leeds, as well as the chaplain and the public executioner. Close by were a handful of reporters, to whom the prisoner spoke his last slowly and clearly. “You know that my life has been base and bad,” he said for their benefit. And then after a few more banal pieties, a slight nervousness became apparent as he prepared to meet his maker.

“Almighty God, have mercy upon me,” he said, “I should have liked to have had a drink.”

The chaplain ignored him. “Lord Jesus, receive his soul,” was all the man of the cloth said. And then, in another account, “the bolt was drawn, the drop fell and [he] died without a struggle.”

And so ended the short life of Charles Peace, one of the most colourful characters in Sheffield’s history. With a father who had been a lion tamer, the younger man had, at one point, been hailed as “The Modern Paganini” for his prowess with the violin. Despite this unusual pedigree, any artistry or subtlety was long overshadowed by the more prosaic labels that became attached to his name.

Murderer, burglar, fugitive from justice, professional vagabond, ne’er-do-well and master of both disguise and evading capture. Even when the authorities finally caught up with him, he subsequently jumped off a train en route to a court hearing and knocked himself out.

After that subsequent trial which now brought him to the gallows, two guards had been placed in his cell each night to make sure he didn’t get up to any of his old tricks.

Small wonder. In Victorian England, Charlie Peace’s exploits had been compelling and shocking news for years. In several accounts, he gave Arthur Conan Doyle the idea for Moriarty, a master criminal who used many aliases and disguises. And had he not returned to his métier — when Londoners lived in fear of his clever burglaries (at least 26 were ascribed to him) — he might have remained free. There had been a nationwide manhunt, enlivened by Charlie’s disappearance and changing appearance. At just 5’3” in height and with a missing finger, he used a prosthetic arm and had help from several women and mistresses to evade capture.

As a cat burglar, Peace was perfect: short, agile and very strong. If the story ends with a sensational hanging, it began improbably in Darnall, which in the 1830s was a sleepy backwater.

And it was an industrial accident at a steel mill that started him on his life of crime. Charlie’s career in a factory ended when he was 14 with a piece of red hot steel entering his leg below the knee. Charlie spent 18 agonising months in Sheffield Infirmary, and was, as was said at the time, crippled for life.

By the time he was 22, he was found guilty of a number of burglaries and jailed for four years. Then a regular pattern emerged: he was imprisoned, released and committed more inventive burglaries and was then jailed again. By 1859, he had moved to Manchester where he removed jewellery from houses that was later found in a hole in a field. Sent to Wakefield Prison, Charlie was given repair work until one day he somehow managed to hide a small ladder in his cell. A warder apprehended him as he was cutting a hole in his cell roof with a saw fashioned from loose tin. He escaped, ran along the roof, fell when some brickwork gave way and ended up hiding in the governor’s house. It was there in the great man’s bedroom where he was caught changing clothes.

More pilfering followed and then capture in Broughton, Manchester where he was found “fuddled” by whisky. After six years he was released, then seems to have kept on the straight and narrow. For a while, Charlie was working as a picture framer and also developed his skill on the violin. Then came another criminal episode prompted by his infatuation with a neighbour. What sounds like a biblical allegory, ended with another: murder.

The irony was, Charlie had married in 1859, and settled down in Darnall. There he became acquainted with a civil engineer called Arthur Dyson, a near neighbour. His wife was a luminous presence called Katherine. Peace was always finding excuses to talk to her. “You see I am here to annoy you, wherever you go,” he said on one occasion.

In the end, the Dysons moved to get away from his attentions to the suburb of Banner Cross, which soon became forever associated with Charlie Peace. Immediately before that, Charlie had been in Whalley Range in Manchester “on business” — clearly, his kind. He had been casing several properties, attempted entry into one, but was seen by one policeman. Then, in his later explanation, as he scaled down a wall, another copper was waiting. Charlie later explained he “almost fell into his arms”. The burglar had strapped a pistol to his arm to make sure it couldn’t be removed.

“You stand back, or I’ll shoot you,” he shouted.

Firing wide, Charlie later noted in court, “they are a very obstinate lot, these Manchester policemen.” There was a tussle, a truncheon was pulled, another shot rang out, and the policeman was wounded, dying two days later. A couple of local brothers by the name of Habron were arrested and, with typical chutzpah, Charlie attended their trial for the murder. When the younger brother was sentenced, Charlie made no comment until he himself was later facing the gallows.

“But now I am going to forfeit my own life and nothing further to gain by further secrecy,” he said from his Leeds cell, leading to a subsequent acquittal for the Habrons.

By October 1876, Charlie was back in Banner Cross, where his infatuation with Mrs Dyson turned sour. The first the locals were aware was when she was heard by several people screaming — “Murder! You villain! You have shot my husband!” — and then, for the next two years, the gunman disappeared. There were sightings in Hull, Manchester, Nottingham and South London.

Charlie’s description was widely circulated — “He is thin and slightly built” — but he had the luck of the devil with several close shaves and escapes. One took place in Nottingham, where he was in bed with a mistress when two policemen came in. Claiming he was John Ward, “A hawker of spectacles”, Charlie asked for privacy while he changed. They let him do so. Needless to say, Charlie jumped out of the window.

Remarkably, he settled in South London with his family and all was fine until a spate of robberies came to the police’s attention. On 10 October 1878, an alert police constable spotted a flickering light in a drawing room in a house at the back of St John’s Park, Blackheath. It was around 2am in the morning. With colleagues whom he called for back up, they waited, and soon a small figure emerged. Charlie promptly fired at the constable — “Keep back or by God I will shoot you!” he yelled — who then charged the burglar.

The policeman was hit in the arm by the fifth bullet (“I’ll settle you this time,” Charlie shouted). It went clean through the constable’s right arm above the elbow. The burglar was overpowered and about his person were discovered his professional paraphernalia — an augur, a centre-bit, a hard vice, a gimlet and some screws.

After a trial at the Old Bailey for the attempted murder of the Blackheath policeman, he was tried in Sheffield Town Hall for the actual murder of Arthur Dyson two years earlier. Held in Pentonville, he travelled with guards up on the train. After leaving London early on the second day of the remand, Charlie managed to escape despite the proximity of the guards. One held on to him as he dangled from the speeding train for at least two miles. Charlie escaped and fell close by Kiveton Park. He was later found unconscious by a search party.

There was a delay of eight days before Charlie Peace was declared fit to be tried at Leeds Assizes. What became known as the Banner Cross Murder was a sensation.

“So great was the number of persons eager to be present at the trial that it was found necessary to issue tickets,” The Guardian noted, “and resolutely refuse admission to all who were unprovided with them.”

In many ways, the trial had all the hallmarks of a penny dreadful: stalking, psychotic behaviour (“He said he should blow my brains out and those of my husband also,” Mrs Dyson recalled on the stand) and in her, a victim or possibly a femme fatale depending on your point of view. Certainly, she was not quite as innocent as she seemed. Charlie’s defence lawyer produced an incriminating collection of photographs, billets-doux in her fair hand and peremptory orders to provide him with alcohol. Several suspected Charlie might have forged them, but her testimony had everyone else in court agape.

The events in Banner Cross were recreated in detail with several witnesses who had seen Peace in the neighbourhood. Putting her five year old to bed in the back room, Mrs Dyson was aware her husband was reading downstairs. When Peace suddenly appeared in the hallway — “Speak or I’ll fire!” he said — Mrs Dyson screamed, which attracted the attention of the husband.

Mrs Dyson heard the noise of one bullet and on the stand described the trajectory of the next. “The bullet took affect on my husband’s left temple,” she said quietly. “He fell immediately.” Attended by a surgeon, Mr Dyson was found profusely bleeding. He did not regain consciousness. Later that night, Arthur Dyson was pronounced dead.

But was there more to the story? Peace’s defence counsel suggested an “improper intimacy”. They had, for example, the summer before met at the annual Sheffield Fair.

“How was it you came to be photographed with Peace?” he asked.

“He was at the fair and met me and wanted to go in and have some photographs taken and I went.”

The defence detailed letters, assignations, clandestine meetings — most of which she denied — and something to offend Victorian sensibilities about womanly good behaviour.

“Have you ever been turned out of the Halfway House at Darnall for being drunk?”

“No.”

The lawyer asked Mrs Dyson to look at the landlady waiting in the public gallery. A look of recognition passed between them.

“I may have been slightly inebriated,” Mrs Dyson admitted to laughter which broke the tension.

Whatever had really gone on between Peace and Dyson could not eclipse the brutal reality of murder. Five other witnesses reported Charlie Peace’s presence around the Dyson home that same evening. After 15 minutes, the jury returned with a guilty verdict. Nobody was in any doubt what would happen next. The Judge passed upon him “that sentence which is the only sentence the law permits in a case of this kind.”

Early the next day, Charlie prepared to meet his maker, with words that he was often quoted as saying which feel like a fitting legacy:

Lion-hearted I have lived

And when my time comes

Lion-hearted I will die.

Nicholas Booth is the author of “The Thieves Of Threadneedle Street”, a book about a famous Victorian forgery and series of manhunts across the world which took place in 1873.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.