Good afternoon members — and welcome to today’s newsletter.

Today’s story is about Sheffield’s much-loved Crucible theatre, which will be 50 years old in November. Nowadays the theatre is very much part of the furniture in the city, but in the late 1960s a huge row broke out over its creation. A new book tells the story of that battle.

Mini-briefing

- Sheffield local democracy reporter Molly Williams revealed last night that the council's long-awaited local plan has been pushed back again to December 2024, a full year after the deadline the government set. Sheffield’s other local democracy reporter Lucy Ashton tweeted: “This is not good news. With no Local Plan the council is in a weaker position to fight unwanted developments. It said itself earlier this year it was ‘a risk’ not having a Plan in place.” The Tribune reported on Sheffield’s lack of a local plan here.

- The Star reports that the starting price for Sheffield’s Old Town Hall will be just £750,000 when it goes under the hammer in London next month. The crumbling Grade II listed building will be sold by Allsop auctioneers on November 9, with interested parties asked to register ahead of the sale. A spokesman for Allsop said: “It is a very interesting asset and we’re sure it will create a certain buzz.” As The Tribune reported two weeks ago, the Friends of the Old Town Hall are calling on the council to step in and buy the building instead.

- The BBC report that South Yorkshire steelmaker Liberty is to reopen their Rotherham plant after securing a £50m cash injection which it says will safeguard 660 jobs at the firm. The company has been looking for new financial backing since its previous lender Greensill collapsed in early March. GFG — the company which owns Liberty — said the money would allow the firm to restart its electric arc furnace at its Rotherham factory. But there is no news yet on the future of Liberty’s Stocksbridge facility. The local MP Miriam Cates has recently called for GFG to sell off the Stocksbridge plant.

- The Sheffield Modernist Society currently has an exhibition on at South Street Kitchen at Park Hill flats of photos of modernist churches in South Yorkshire. The photos, which are all by Sheffield photographer Ian Justice, question the role of such buildings in an era of declining church attendances. The exhibition is on until November 21 (and South Street Kitchen does great coffee and food as well). And Heeley Art Club are currently hosting an exhibition of painting at the Winter Garden. The art club is the oldest in Sheffield (established 1895) and the exhibition runs until Sunday. All the artwork on display is for sale.

In just under a month’s time, on November 9, 2021, the Crucible will celebrate its 50th birthday. The world famous theatre is now a fixture in Sheffield: as much a part of the city as the Cathedral or Town Hall. But it wasn’t always like that. When the idea of a new theatre was first mooted in the late 1960s, the UK’s theatrical establishment and Sheffield’s local media fought a bitter campaign against its revolutionary design. Knights of the realm, local councillors and The Star newspaper all campaigned vociferously against the project, but a group of young radicals who wanted to create something new and different won out.

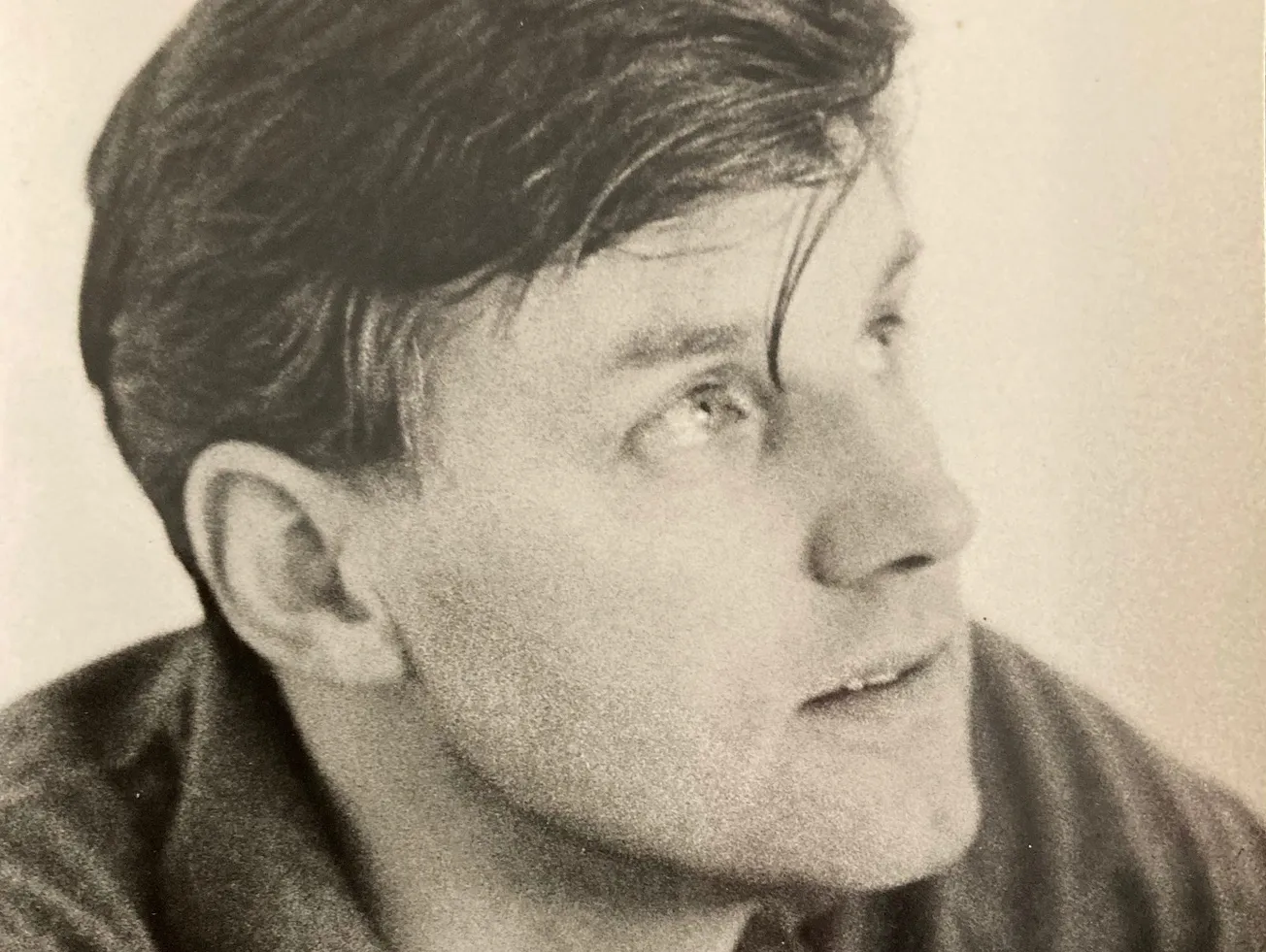

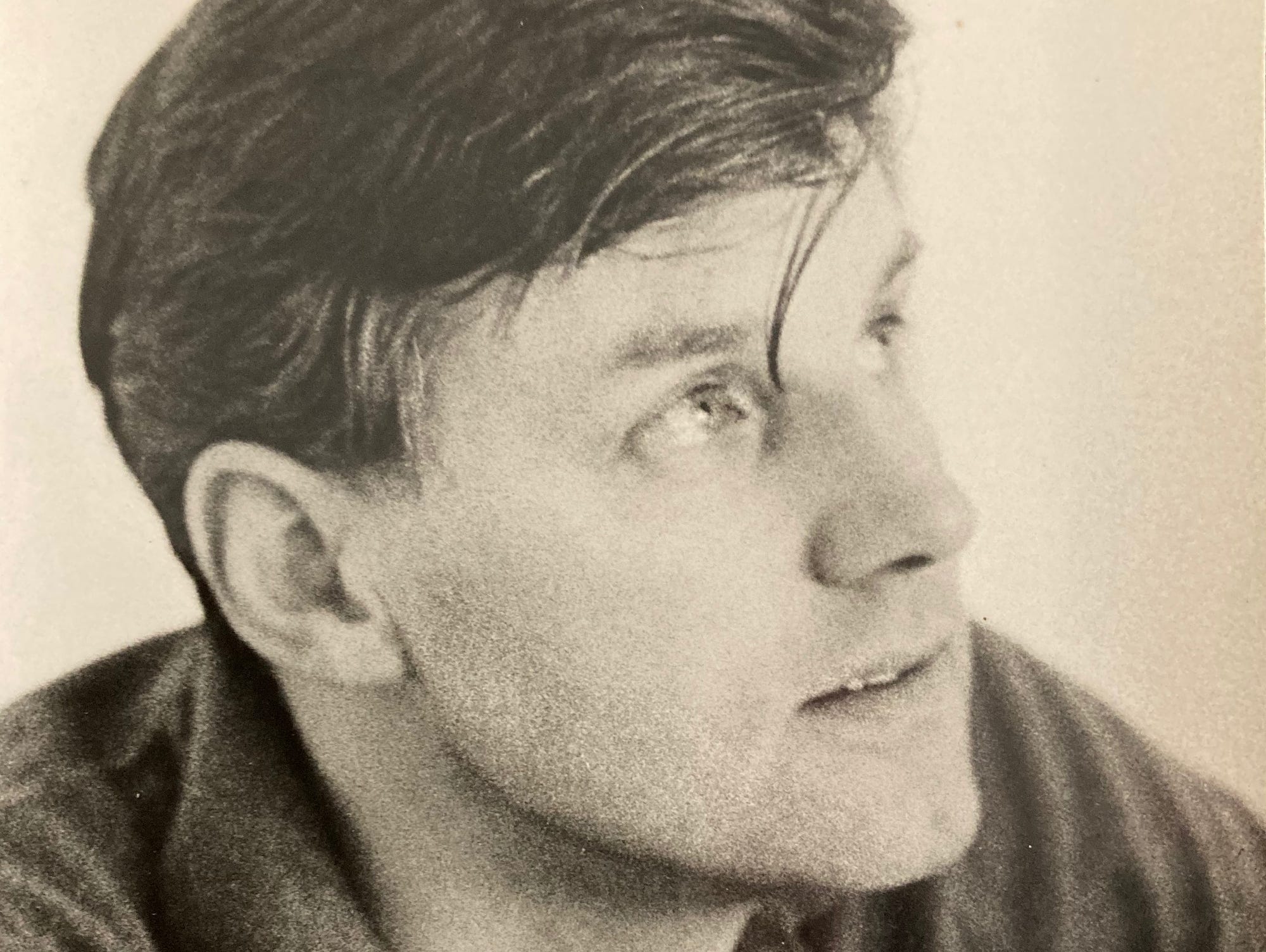

A new book written jointly by Colin George, the Crucible’s first artistic director, and his son Tedd, details that fight. Stirring Up Sheffield: An Insider's Account of the Battle to Build the Crucible Theatre is a tale of heroes and villains, traditionalists and radicals. But it has taken a long time to get to this stage. Colin sadly died in 2016 and the book has been finished off by Tedd, who spent the recent coronavirus lockdowns researching and writing a book that had been gestating for the better part of 50 years. “It is literally almost half a century since my father started work on it,” Tedd told The Tribune from his home in Hampstead last week. “It’s been a long time coming.”

Colin George first came to the city in 1962, when he was appointed assistant director of the Sheffield Playhouse. In 1965 he would become director of a theatre company which already had a reputation for staging local, experimental work like the musical Stirrings in Sheffield on a Saturday Night. But its home — a former temperance hall on Townhead Street — was wholly inadequate for the kind of work they were showing, and in 1966 the process of creating what would become the Crucible began.

Sheffield wasn't the only place where new and radical theatres were being built. During the 1960s there had been a wave of modern auditoriums constructed across the country including at the Chichester Festival Theatre in West Sussex. The booming economy of the 1960s meant there was lots of money around and public bodies like the Arts Council and Sheffield City Council were prepared to fund new theatres.

After much discussion it was decided that the new theatre would have a “thrust” stage, in which the actors are surrounded by the audience on three sides. Theatres had been designed using a traditional “proscenium arch” design (where a stage sits at the front of an auditorium with banks of seats facing it) for hundreds of years. But in the postwar period new theatre designs sought to bridge the gap between actors and audience.

Tedd says Sheffield City Council’s leadership were “visionary” in pushing for a contemporary design. While they hadn’t specifically said they wanted a thrust stage, they did make it clear they wanted something modern. And, crucially, they were prepared to back the creative people to deliver it. “There was a lot of experimentation in theatre at that time,” says Tedd. “Some succeeded and some failed — but by god they got it right at the Crucible.”

As well as the revolutionary auditorium, the attention to detail in the entire building is astonishing. Nick Thompson, the architect of the Crucible, wanted the doors to the main theatre to give theatregoers the feel of entering a totally new realm, and were therefore modelled on the entrance to Agamemnon's tomb in Mycenae. Thompson also loved Italian hill towns in which walkers are constantly presented with new and interesting vistas. The Crucible’s entrance, foyer and bar area was designed to provide a similar level of visual interest and variety as you move through the space.

“Dad just got together the perfect dream team,” says Tedd of the Crucible’s design process. One of the most important of these was theatre designer Tanya Moiseiwitsch. She had already designed several thrust stages and put to work all of her experience and learning from her previous projects into the Crucible. They then assembled a group of brilliant young architects and engineers who turned Tanya’s drawings into the steel and concrete needed to produce what Tedd calls “the most perfect thrust stage in the world.”

But not everyone was a fan. One of the theatre’s major opponents was actor, writer and director Sir Bernard Miles, who had opened London’s Mermaid theatre in 1959. While others including Sir Laurence Olivier and Sir Alec Guinness also expressed reservations, Miles led the campaign against the theatre's design. For Miles, the Crucible’s stage would create “second and third class citizens” by putting them round the side of the auditorium, with some in the audience restricted to “a back view of Hamlet’s legs”. He continued:

“I think this stage is a kind of freak. It is a retrograde thing, and it will be out of date in seven years’ time.”

50 years on, these complaints seem quaint and old-fashioned. The Crucible’s huge success has vindicated its radical design. The thrust stage, far from excluding members of the audience, acts to include them in the action more than in traditional theatres. “If you see someone from behind it can be just as dramatic as you see the person they are talking to and their reaction,” explains Tedd. “The idea that if you can't see the front of the actor you can't enjoy the performance is complete rubbish.”

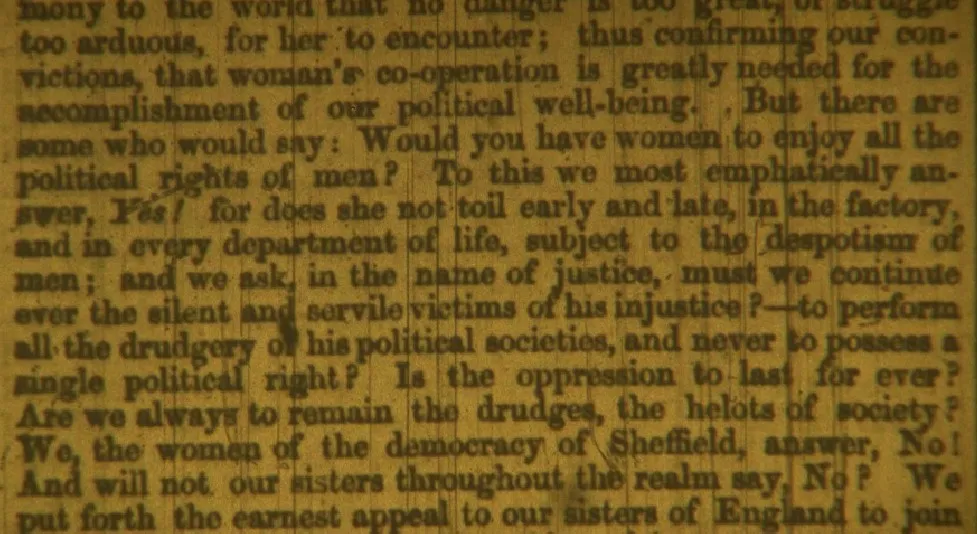

In the late 1960s, however, Sir Bernard’s criticisms were seized on by the conservative establishment in Sheffield. These included local councillors (one Tory councillor bemoaned the fact that the thrust stage meant there would be no more performances by the Black and White Minstrels) and the city’s established print media. In September 1969, two Conservative councillors, Martyn Atkinson and Michael Swain, described the project in The Star as a “wastage of public expenditure” and “another white elephant like City Hall.”

But there were also letters of support from theatregoers in Sheffield, who urged George to continue with his plans. One, Ivan Norris of Norton, wrote:

In my opinion the “thrust” stage (unhappy word) offers a much greater scope for a whole range of art forms from our new writers, producers, musicians and actors, than can ever be achieved with the proscenium stage, with its problems of acoustics, lighting, limiting of vision, etc. Let us leave our proscenium viewing to the telly box, the source of so many of our prejudices, and welcome the new theatre, Carry on Colin.

“The Star represented a group of people who were more traditional,” says Tedd. “They thought if they had the thrust stage they wouldn't be able to enjoy things like pantomime or ballet. They also thought it was pretentious. But once the Crucible opened and gradually became a success, they changed their tune and actually wrote an apology.”

Printed in the paper a few weeks before Colin George left the Crucible in 1974, the apology mentioned the conflicts George had found himself in with those in the city who were “reluctant to engage and experiment” (presumably meaning themselves). It added that he was bowing out with “characteristic assurance and grace”, having established himself in Sheffield as “something of a legend”. It continued:

Success and acclaim for the Crucible were not instantaneous, but when they came, they were on a scale which we are now happy to admit proved the extent to which Mr George was right in his firmly-held beliefs and to which we, conditioned by traditional ideas of the shape of a theatre and its aspirations, were wrong. Today, we are happy to congratulate Mr George on the success that marked his bold endeavours. For what he has done has been far more than scoring a personal victory. He had endowed Sheffield with a modern theatre, as venturesome in its productions as in its design. He has given something of lasting value.

Tedd (who is an economist by trade but also works as a broadcaster and writer) says he’s never worked on anything as personal as Stirring Up Sheffield. As well as being the story of the birth of the Crucible, the book documents the creation of his family. Colin only met Tedd’s mother Dorothy after moving to Sheffield, and had his two sisters and then him while they were living in the city.

And he said the act of editing his father’s original manuscript — adding and revising sections and trying to capture his father’s voice — made him sometimes lose track of who’s words were which. In the foreword to the book, Tedd says sentences would “tumble onto the page” as if they had been written by Colin. “If I was indeed ghost-writing my father’s book,” he writes. “Then his ghost was writing through me.”

But the promise he made to his dad has now been fulfilled. In the face of bitter opposition, Colin George created a theatre that is loved by the city of Sheffield and admired around the world — but whose turbulent creation had never been fully explained until now. “I think the story of how the Crucible came about has now been told,” he told me. “I think this explains it.”

‘Stirring Up Sheffield: An insider’s account of the battle to build the Crucible Theatre,’ by Colin George and Tedd George, will be published by Wordville on November 9, 2021, the 50th anniversary of the Crucible’s opening. If you would like to get a signed and numbered copy before then, you can order one at www.wordville.net/product-page/stirring-up-sheffield.

The book will be launched at the Crucible at 3pm on Thursday, November 11, when the co-author Tedd George will give a talk on the book and the controversy that the theatre stirred up. If you would like to attend the free event, email info@wordville.net.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.