The banners were painstakingly strapped to the ‘Welcome to Sheffield’ signs on the city’s main entry roads. As the cars zoomed past, some of the drivers peered out at the block lettering, checking they’d got it right the first time. ‘Sheffield: Lesbian capital of the north.’

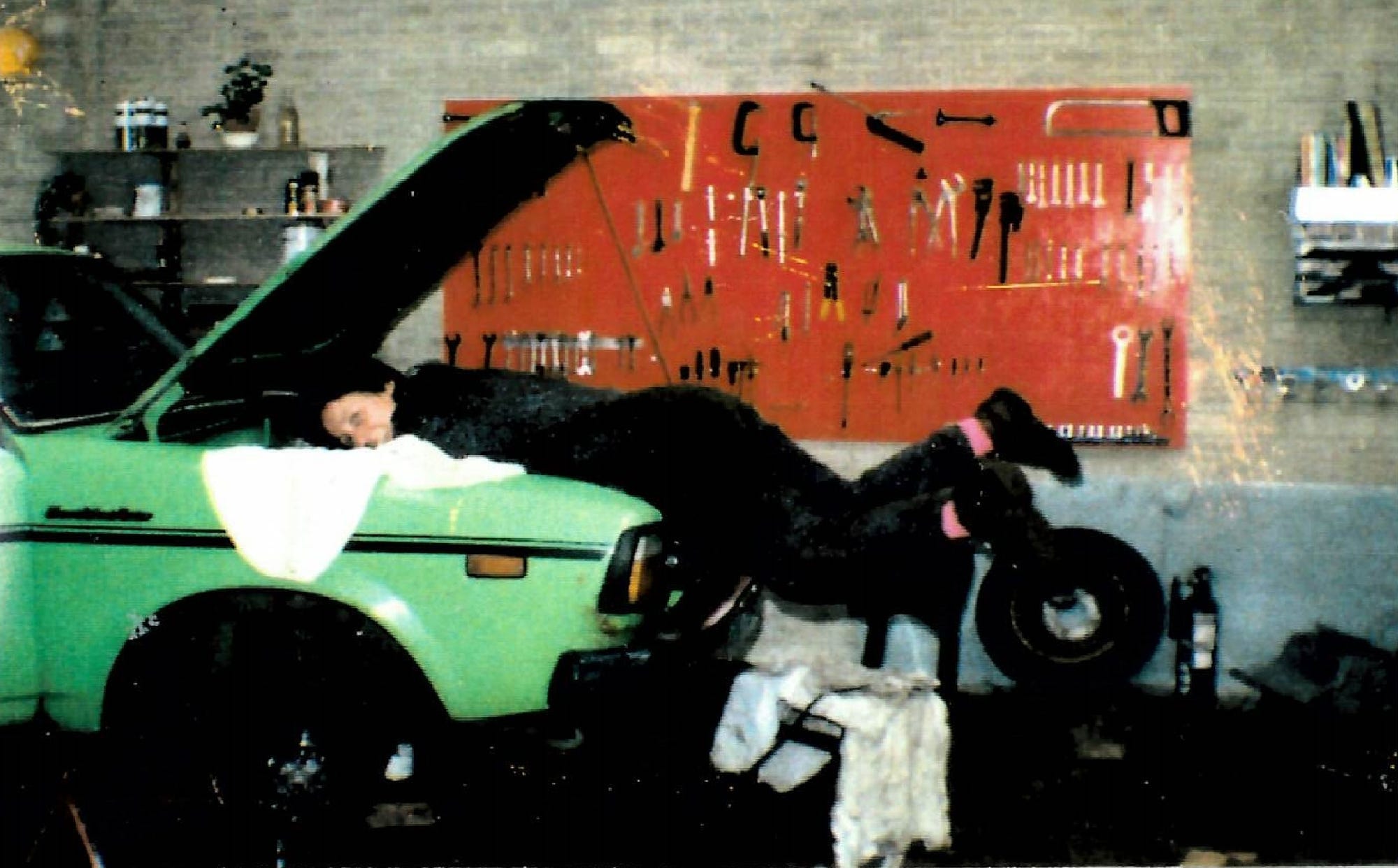

The woman behind the banners, Ros Wall, was just one of three gay women who ran Gwenda’s Garage — one of the only all-female owned garages in the country. One of their former employees, Bee Rowan, tells me she thought the garage was “world-changing.” But she’s quick to stress that the owners probably wouldn’t agree with her: “They’d said this is normal, this needs to be normal, this shouldn’t be any different. Whereas I was very acutely aware that this was different.”

When Ros Wall, Roz Wollen and Annette Williams opened the doors to Gwenda’s Garage on an industrial estate in Neepsend, it was May 1985. The year-long miners’ strike had just come to an end and Greenham Common was occupied by the Women’s Peace Camp. “The thing about Gwenda’s Garage was that it was part of something a lot bigger,” Roz Wollen, the last remaining member of the original trio, tells me via video call. “People sort of say 'oh, Gwenda’s Garage was amazing' but in actual fact there were lots of things going on at the time for women, done by women, and it was a huge buzz.”

Arguably, the story starts roughly a decade and a half earlier, when 16-year-old Roz “persuaded” her parents to gift her a blue and white Vespa. Context was on her side: school was a long way from the house and she didn’t live on the bus route. “I think I felt independent and it gave me a taste for always having my own wheels.” Roz wasn’t sure what to do after school — a stint in a cigarette factory was followed by time working in an adventure playground in Southampton, then a course in youth and community in London when she was in her late twenties. Aged 30, she decided she wanted to get out of London, scored a role as a youth worker on a job creation programme and moved to Sheffield.

Ever since owning the Vespa, Roz had been the proud owner of any number of scooters and motorbikes. The problem was, she didn’t have mechanical smarts at the time, so any issue was followed by a trip to a garage, where she’d shell out £20, £30 for the pleasure of a diagnosis: that her engine was broken. Eventually, the joke got old, so the next time round, she stripped the bike down and rebuilt it with the help of a colleague. She had plenty of reason to get more interested in the inner workings of motorbikes: in her role as a youth worker, she often took the girls she was working with out on motorbikes to whizz about the woods (“it was something you just couldn’t do anymore”, she says). And those bikes broke down a fair bit, too.

All of this was sufficient motivation for her and her colleague Annette to do a TOPS course — eight months at a skills centre where “you learned all about motorcars”. But once they qualified, there was a plot twist. Nobody wanted to take on two women in their early thirties with just eight months’ experience. Reluctant to hang up their spanners, they decided to open Gwenda’s. Roz stresses that this was a purely practical decision: “We set up Gwenda’s out of necessity,” she says. “Not because we wanted to set up a women’s garage.”

The name was easy — they’d name it after the record-breaking racing driver of the ’20s and ’30s, Gwenda Stewart. Money was trickier, but luck was on their side: they received government funding in the form of rent-free premises because they were a new business (and not because they were women, Roz emphasises). Their new home was a doer-upper, so it was fortunate that they knew so many tradeswomen who could help them, such as electrician Mary Allebone and sociology-graduate-turned-plumber Em.

Originally from London and with a background of using her plumbing skills to help make empty housing habitable for those on low incomes, Em Lawless had moved to Sheffield in the early eighties. Like Roz, she wanted to equip herself with practical skills.

Em agrees that working as a tradeswoman felt like a political act, telling me it felt important for women to do things for themselves. “At some point I had this image of, if all the men in the world dropped dead, we wouldn't be able to mend our electrics or do our plumbing,” she says. “It's quite frightening really, that all of that knowledge is held overwhelmingly in men's heads.”

Set up as a legal partnership, there was no one person in charge. Roz, Ros and Annette, who all worked full-time, were paid equally. Roz describes the three as “very green” when they started out, recalling it took them a long time to get services finished. But, she says, they worked flat out, serving both male and female customers, and quickly began turning a profit, though she concedes she can’t remember how much they were making.

Whatever the figure, it was enough to hire Bee Rowan from Bradford. Bee had been a politically-minded Peace Studies student, when she’d fallen in love with mechanics via a gold Russian Simca, her first car. Much like Roz, she didn’t have much of a clue about cars at the beginning. But, after enrolling on a mechanics evening course to remedy this, it was a revelation.

“For me, it felt like a very political action to take to learn how to understand how to change a wheel, the oil, the water — all of that kind of stuff — and to make the car accessible as a result to lots of other women. Because nobody had very much money — I certainly didn't.” She talks of mechanics as having been this mysterious world that had been shut to her. “It was a very male world and there it was, opening, and my god, it made sense!”

Roz, Ros and Annette weren’t just good mechanics. Like many other women living in the Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire at the time, they were activists. While Roz disputes that the garage was a hub for feminist campaigns, it sounds as if the three were very much at the heart of the political action at the time.

Roz recalls protests and spray painting, telling me there was a lot going on. “There were quite a lot of women who were lesbians who were being threatened with having their children taken off them by their husbands, there was the whole Section 28 going on, so that [campaigning] community was very important.” While all three women were gay, Roz recalls Ros being particularly involved in rallying against Section 28 ‒ the legislation that prohibited the "promotion of homosexuality" by local authorities. It was Ros who constructed the banners after her shifts, of course.

Roz took a different approach, and under the auspices of a Lesbian Line — a volunteer-run telephone helpline for those needing to talk about their identity — she set up a support group for teenage girls that were coming out. The group made headlines when they were uninvited from speaking at a school.

“There was a whole furore by the parents saying that it was promoting homosexuality in school, so the education office said there's to be no more talks in schools by young lesbians or any gay people,” she says. “And then we picketed the educational committee and that got in the paper. We each had our own different things we were involved in.”

It’s this intersection of the practical and the political that attracted Nicky Hallett and Val Regan, from the LGBTQ archive group Out of the Archive, to collate oral histories of both Gwenda’s and activism in the 80s and create a brand new musical about the garage, which will be running at the Crucible Playhouse from 13th-14th November. The dates have been chosen in order to come close to the 20th anniversary of the repeal of Section 28.

“It just seemed a fantastic story,” Nicky, the project’s writer and researcher, tells me. “We'd heard of it so often in different ways and different anecdotes people told us.” Val, a community musician, tells me that the purpose of Out of the Archive is to record a history that might otherwise be forgotten. She reminds me that, although LGBTQ+ rights have moved on “tremendously in the last few years”, it has been just over 50 years since homosexuality was decriminalised ‒ a relatively short period of time within a culture’s history.

“A culture that hasn't been able to live in the open is a culture that can't tell its own stories, can't know or own its own history,” Val says. “So I think it feels really important to us that we record that history.”

Gwenda’s would go on to be sold in 1990 — after becoming VAT registered, the business became less profitable as they struggled to compete with backstreet garages, and Ros and Annette had been invited to teach women about mechanics on positive action courses. The garage was sold as a going concern — though they refused to pass on the name, Roz tells me. “We felt it was a women's garage, and Gwenda Stewart was a woman,” she says. “And we felt like we didn't really want to hand that bit on.”

Roz, meanwhile, wasn’t quite ready to teach. Instead, she was hired by the AA as a breakdown patrol woman (an appointment that would again put her in the news, being the first woman in the north to get the job and the second woman in the country). There were things that she loved about the job but she found it “quite lonely,” with its antisocial hours.

“It was a very good job in terms of me entering mainstream motor vehicles,” she says. “I was no longer in a fringe garage, I was on motor vehicle patrol, I was out there doing it and hacking it like blokes were, late at night and early in the morning.”

But after two and a half years, she’d had enough of the unsociable hours and was lured into teaching. At Sheffield College, she set up a women's course in mechanics and spent the next decade passing on the skills that she’d honed with her friends at Gwenda’s to the next generation of women (and some men — though she describes them as “guests” of the girls). She tells me her time teaching was hard, too. “There was pornography put behind my desk by some of the guys that taught there. It was deliberately pointed at me.”

In the last 13 years, Roz has lost both of her co-founders and friends, Ros and Annette, to cancer. These days, much of her energy is dedicated to her work as a trustee of Women in Engineering, Science and Technology (WEST) — a charity she helped to co-found in Ros Wall’s name and with money left in her will, aiming to inspire girls and women to study and work in non-traditional trades and careers. WEST, Roz says, is Gwenda’s legacy. It offers bursaries for women training in a trade or engineering, they send tradeswomen to schools to talk to boys and girls about their jobs and they do activities with them that aim to teach them about the very basics of engineering.

According to Engineering UK, the number of women in engineering has increased substantially, from 562,000 in 2010 to 936,000 in 2021. However, within trades, Roz says that figures are less optimistic. It’s a view that the Office for National Statistics seems to confirm, with stats from last year revealing that, of all skilled trades professionals working in the UK construction sector, just 1% are women.

Roz is right; Gwenda’s was part of a bigger movement and WEST’s mission to support women and girls in 2023 is the garage’s lasting legacy. Bee claims that the very fact that Gwenda’s existed in and of itself for that length of time is testimony to that this can happen any time. “It's a flag of possibility. It's also a legacy to women generally.”

She argues it should also be a legacy to every careers teacher in the country. “Often girls are steered in a particular direction, which the careers teachers have been schooled into supporting and often those teachers don't have access to examples. ‘Hey boys and girls! Look, this happened in the eighties! It's doable.’”

Gwenda’s Garage will be on at the Tanya Moiseiwitsch Playhouse from 13-14 November. To book tickets click here.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.