I’ve only been in Page Hall for half an hour when the police stop me. I’ve seen them a few times already, crawling the area in their patrol car and parking up in plain view in the tiny north-east Sheffield neighbourhood. Pulling up beside me as I walk down Hinde Street, the officers tell me that my presence is arousing suspicion in the area, and the implication is that I should leave, so I do. Later I find out that three fights broke out in the days before I come by. While I’m there, half a dozen police patrol cars and vans circle the area hoping to deter a repeat occurrence.

Reporting on Page Hall isn’t new to me, but it’s been a while — back in 2018, I wrote a story about neighbourhood tensions in the tangle of terraced streets close to Northern General Hospital. In Sheffield, the area is best known for its large Roma population, who began to arrive in significant numbers after Slovakia joined the European Union in 2004. But Page Hall already had a Pakistani Muslim community that traced its roots back in the area for more than 50 years. Perhaps inevitably, to some in the well-established British Asian population, the Roma newcomers felt like a threat.

These tensions were first publicised in 2013 when local MP and former home secretary David Blunkett gave an incendiary interview to BBC Radio Sheffield when he warned of “an explosion” in the area (warnings that he would later walk back from). A follow up piece in The Guardian said anti-social behaviour, theft and prostitution in the area were rife. The same story also mentions allegations — never proven but reported in the Daily Express — that a Roma couple had tried to sell their baby to a local shopkeeper for £250.

Five years later it looked as though Blunkett’s prediction might have come true when a fight at Fir Vale School between Muslim and Roma pupils threatened to spill out into the wider neighbourhood. A few weeks later, a furious public meeting I attended descended into a slanging match between local Asian landlords and angry members of their community who accused them of renting out properties to tenants they deemed unsuitable. The implication was clear enough: these tenants were Roma people, who the community seemed to think were troublemakers. I wanted to find out what had happened in the four and a half years since. Had things got better?

After my run in with the police, I return to the neighbourhood more than half a dozen times over the next few weeks. I had hoped this might be quite an easy story for me to write: visit an area I knew reasonably well both from my time at The Star and from living in nearby Pitsmoor and see how it’s changed.

But it didn’t really work out like that.

Five years on

“Sebastian!” A man on Hinde Street shouts to his son in the house on the other side of the road. “Sebastian!” he tries again without any luck. Further down a tiny girl of maybe five smiles at me as she scarpers past clutching a carrier bag which looks like it’s filled with sweets. Dressed in pink pyjamas, she has big gold earrings in both ears. The house next door is completely boarded up.

The first thing that strikes you when you walk around Page Hall is the amount of poor-quality housing. Some properties are so bad they look like they’ve been condemned (or ought to be). Dozens of windows are boarded up or broken and walls seem to be crumbling before your very eyes — though roads are also dotted with better-maintained properties.

The other aspect is the litter. A thin dusting of crisp packets and drinks cans sometimes feels like a sort of tax we all pay for living in urban areas in austerity-era Britain, and that’s the level of rubbish you get in some streets. But in other parts, flytipping is rife. Full bin bags are dumped outside bins while in other parts of the estate mattresses and furniture are abandoned on the pavement. On one street I walk down a dead rodent sits squashed in the middle of the road. All this, as you might expect, is having an effect on house prices. The average price of a terraced house here is just under £100,000, but many in the area go for less than £50,000.

While walking through the neighbourhood, I think about the challenge that faces me — two challenges, really. The first is obvious: the Roma community in this area has not received much good press over the years and are understandably wary of outsiders.

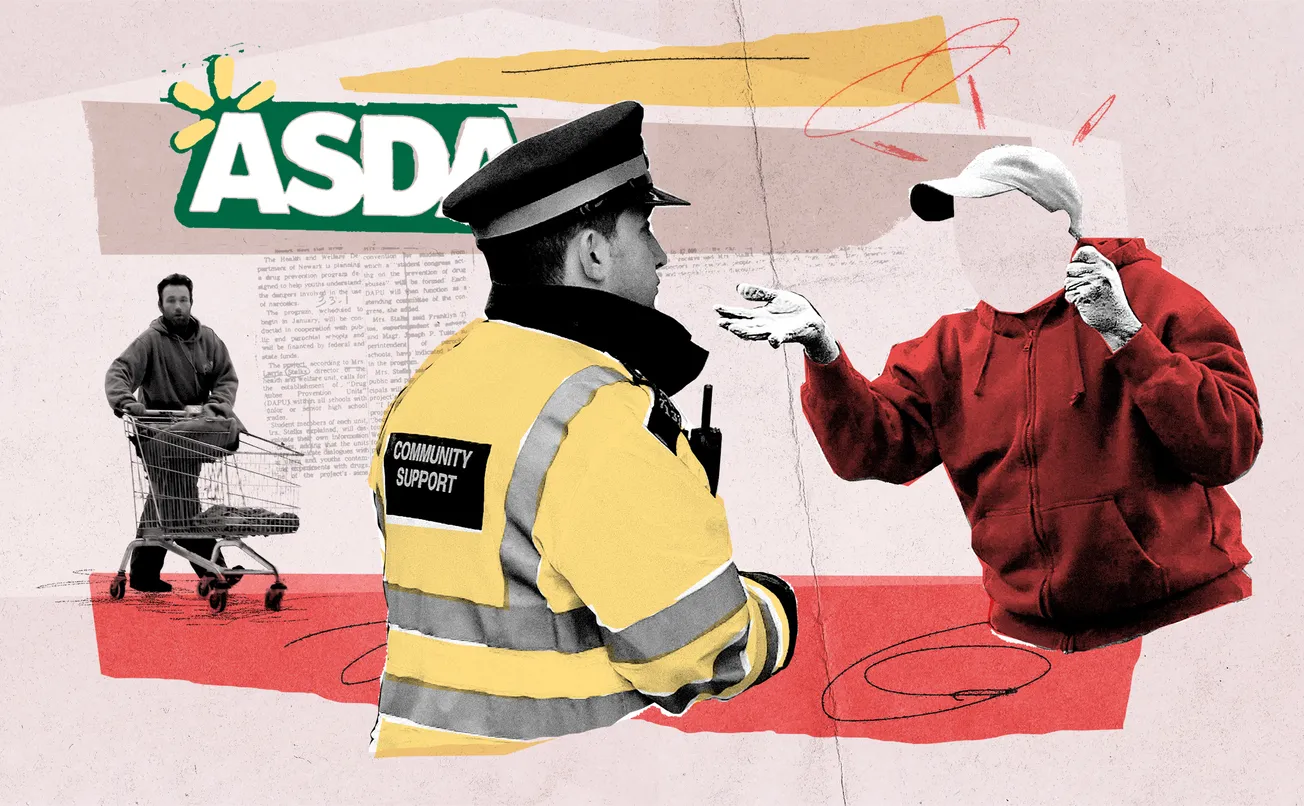

Then there’s the second. The intermittent visits paid by South Yorkshire Police’s tactical aid unit van — more commonly known as the riot van — following those three fights. People are on edge, and that’s not helped by the media coverage which followed the fights, which was typical of the sort of reporting this area normally receives. “All hell let loose,” one resident told The Star about one incident in which dozens of people were pictured fighting on Hinde Street. Later in the week, police revealed that they had arrested three men and one woman on suspicion of violent disorder. They also said a 13-year-old boy had been arrested on suspicion of possession of an offensive weapon.

But I’ve set out to do this story, so I try to shrug off the wariness that people greet me with and the language barriers. On Page Hall Road, two Roma women walk past me with big umbrellas in the rain. As I try to explain why I’m there I think I’m getting somewhere until the older woman says something I don’t understand to the younger one and the shutters go up again. “I’m sorry, no speak English,” she tells me.

I have a bit more luck further up the road with Pavel, 46, who is smoking a rollie outside his house. He tells me he’s been in the UK for 16 years and works at a local takeaway. He has two kids, one age 10 and one 20. How are community relations in the area now, I ask. He makes a see-sawing motion with his hand to indicate that sometimes it’s better than others. However, his next door neighbours are Pakistani and he says he gets on with them just fine. “I take post for them, they take post for me,” he says. “We get on well.”

A little further on, three lads shout at me from the other side of the street. “Alright, boss?” they shout. The reason for their gregariousness soon becomes clear. It turns out they’re a bit pissed. One of them scarpers before I can get his name but the others, Marco and Marek, are happy to talk.

Both Roma, Marek is 35 and is a more recent arrival in Sheffield. His English is what you might call a work in progress. When I ask questions he habitually requests translations from his friend. Marco, on the other hand, is fluent. He is now 25 and has been in Sheffield since he was just seven.

Like everyone else I speak to, Marco says that the Roma people who have come here have done so to get a better life, nothing more. Schools are a factor but jobs and wages are the bigger draw now. All of his family are currently working and some have businesses of their own. What of the fights, I ask. Have you been to the town centre, he asks me pointedly. “Last time I went there were beers flying, everything,” he says. As anyone who’s been to the city centre on a Saturday night can testify, he’s not exactly wrong.

Settling down

Eventually I head to the Fir Vale Community Hub to seek out Gulnaz Hussain, who I’d last spoken to after the fight at the school five years ago. Her father set up the Pakistan Community Advice Centre in 1989, the same organisation which she now leads. It updated its name in 2012 after the influx of Roma people from Slovakia during the 2000s drastically changed the area’s demographics. Now an employee of hers called Tomas Tancos, who runs the Sheffield Roma Network, holds regular advice sessions for the community at the centre. When I visit one, there are people queuing out of the door.

Gulnaz tells me the Roma community in Page Hall is more settled here now than ever. She estimates that there are “2,000 plus” in the area at the moment, although this fluctuates as people move back and forth between Slovakia and the UK. All are economic migrants, coming to the UK for a better life than they would be used to back home. This includes better employment opportunities for them and better educational opportunities for their kids, things that are routinely denied to them in Slovakia.

Are community relations now better then when I last reported on Page Hall back in 2018, I ask. It’s still tough, she tells me, but some people who may have been quick to criticise the Roma in the past are now more likely to focus on what Page Hall can do as a community to make it better. This included things like joint litter picks and better mixing between the area’s Roma and British Asian populations. But there is also something more: a realisation among the area’s more established British Asian population that the Roma community is here to stay. “We have to try to make it better,” she says. “We have no choice.”

The sporadic violence that flares up from time to time may be a harder problem to fix than the litter. Gulnaz tells me that until this week they’ve actually had a long period with no incidents, but that the later nights often coincide with the return of increased anti-social behaviour. Several videos can be found online of huge fights, sometimes involving up to 50 people, armed with weapons including sticks and golf clubs. She says the fights that occur are all arguments within the Roma community — but she doesn’t try to downplay their seriousness. “There has got to be a greater understanding of what is acceptable and unacceptable,” she says. “People shouldn’t have to put up with it.”

Like any ethnicity, the Roma are not a homogeneous group. Sheffield-based academic Mark Payne has spent eight years researching the Roma community, both in Page Hall and in Slovakia. The first links in the chains of migration appear to have come during the Communist period in Slovakia (then Czechoslovakia), when some Roma sought asylum in the UK. Since large-scale immigration from former Eastern Bloc countries to the UK began in 2004, strong communities from two main Slovakian villages have grown up in Page Hall: Bystrany and Žehra.

However, which of these villages they come from can have a big effect on how they fare in the UK. Payne’s research has revealed that how well Roma children do when they get here can be predicted by which village they come from, with those from Bystrany faring much better in the school system than those from Žehra.

“Bystrany is a nice little village,” Payne tells me as we walk around Page Hall in some welcome spring sunshine. In most parts of Slovakia, and indeed in most parts of Europe, Roma settlements tend to be situated on the outskirts of the towns and villages. In Bystrany, however, they are included in the main village and local schools are also more accepting of Roma children. Žehra, on the other hand, is a “qualitatively more miserable experience”, he says. The schools are nowhere near as good and there is a lot of truancy. The Roma in Žehra are housed on the edge of town.

This in turn has a knock-on effect on how those villages benefit from the back and forth migration to the UK. When he visited Bystrany, Payne says 2,400 of its 3,000 residents were in Sheffield. But even without most of them there, it was easy to see the improvements money earned in the UK has produced. “One man had two kitchens, one just for show,” he says. People from Žehra who come to England tend to use the money they earn here to leave.

It’s a picture that Gulnaz recognises from her work at the community hub. “You can sometimes tell the difference when they walk in,” she tells me. “Communication can be tough with some of the Roma people we see.” But she’s also keen to stress that it would be wrong to blame all the problems of what is a deprived inner-city area on just one group. “Page Hall has always been underinvested in,” she tells me. “It is a much bigger problem than just the people who live here.”

As we walk and chat, Payne talks me through how difficult it is to get a job in Slovakia as a Roma person. Many of them will be rejected out of hand if their names mark them out as Roma (names like Horvath or Zigova are very common in the Roma community). However, even if they do get an interview in many cases an employer will simply see a brown person walk in and say, ‘no thanks’. “A lot of them have never worked at all before they came here,” he tells me. “But as soon as they get here they find work. It is the last acceptable form of racism.”

Better in Britain?

It would be nice to think that Sheffield has proved itself to be more admirable than Slovakia — that we have been more welcoming to the Roma community. But while some parts of life for the Roma are easier here, a recent report in The Guardian found that people from gypsy, Roma and traveller (GRT) backgrounds still experience significant prejudice, discrimination and abuse in the UK. The study, which was based on an extensive survey of GRT communities, found that almost half (47%) of them had experienced a racist assault, while 35% had been physically attacked.

As for the area’s problems, Payne put them down to the rapid influx of Roma people to Page Hall causing “teething troubles”. Anti-social behaviour is more likely as Roma people tend to have larger families and spend more time outdoors, he says. “Most British kids are playing inside on their Playstations,” he tells me. When I ask him about the fights, he believes the issue is “a bit overblown”, and that disorder can be a problem on many estates in Sheffield. Still, he does acknowledge that they are more common here. “While more educated people might settle things around a table with a glass of wine,” he tells me. “In the Roma community it can just kick off.”

Payne connects me with David Kandrac, who lived in Page Hall for 12 years and is now doing a masters in psychology and education. Now 31, he moved to Sheffield at the age of 16 in 2007, three years after moving to the UK from the Slovakian village of Bystrany. His family first moved to Cardiff, but David struggled in school and was excluded. However, after coming to Sheffield he enrolled in an English language course in 2009 and eight years later he got an unconditional offer from the University of Sheffield.

He tells me that Roma people come to the UK for a variety of reasons. These include for work, education, a better lifestyle for themselves and their kids and to escape discrimination. But he acknowledges that adapting from what he describes as a “ghetto” in Slovakia to the UK was difficult for many in his community. “We had to adapt quickly,” he says. “We learned the hard way.”

These differences have also been difficult for some of the communities they have moved to, who didn’t know anything about the community and were unprepared for how different they would be. In terms of the fighting, David says for the Roma, like many English travelling communities, intra-community violence is often a way to settle disputes. “They have beef but they always get back together,” he tells me. “They just sort it out between themselves.”

Other problems like litter are a function of deprivation and overcrowding in Page Hall rather than anything intrinsic to the Roma community, he says. In addition to doing his masters degree, he also works as a self-employed interpreter for the council’s social services department. In the course of this job he says he has seen some atrocious housing and that exploitative landlords are more to blame for the area’s problems than the Roma population.

David is now married and has three children and hopes to become an educational psychologist after he has completed a doctorate in the next few years. He tells me that many in his community are gaining confidence in the UK and now feel like they should be treated less like outsiders and more like the members of the Sheffield community they have become. “The Roma were rejected originally but Sheffield is now their home,” he says. “This is their area too.”

A better life

The difficulties in covering Page Hall I’ve encountered over the last few weeks include ones of language, culture and a general sense of mistrust.

But another issue is that the people who live there are routinely “othered”, as is the area itself. Again, I can accept my own culpability in this. At one point in the gestation of this story I had what you might call a frank exchange of views with my editor in which I told her that walking around the area could sometimes feel a little intimidating. She responded, quite justifiably, by saying it was quite a loaded thing to say.

However, after half a dozen visits I do begin to feel more confident in the neighbourhood. I find that approaching younger people is better as there is more chance they will speak better English. And some of the best conversations I have are with two young Roma women.

Martina Pokutova is now 21 and has been in Sheffield since she was six. She’s originally from Žehra but has only been back four times since she arrived here 15 years ago from Slovakia with her parents. She speaks very good English, albeit with an Eastern European accent, and occasionally pronounces the odd word with a noticeable South Yorkshire twang.

“I think my community prefers it here,” she says as we chat on Hinde Road. “I prefer it here. Since growing up I have become used to this country. There are more opportunities here. Education is good.”

When she left school she found work in factories, something which is common among the Roma population in the area. But even these relatively poorly paid jobs are a world away from the lack of opportunity and low pay they would have to live with in Slovakia. “Everyone who comes here just wants a better life,” she says simply.

Have they found it, I ask. Yes, she says, after a moment’s thought. As well as greater opportunity, Sheffield has provided them with a place they can escape the racism and “lack of respect” that Roma people commonly endure in much of Europe. Is there not racism here, I ask. “Sometimes,” she tells me. “When I was younger some people used to say ‘Slovakian, go back home’ — but people get on better now.”

Martina pushes back against the idea that fighting is somehow an intrinsic part of Roma culture, but does accept the way her community argues can sometimes seem different or unusual to outsiders. “Our communities are lovely people and know how to show the big heart,” she says. “When people don’t get to know each other properly, they judge the book by its cover. I think that’s why everyone is getting everything wrong.”

Later, I’ll chat to Ivana Goreova, 18, outside her home on Popple Street. She’s dressed in a pink Lion King t-shirt and has a tattoo of a feather on her left index finger. She’s lived in Page Hall for four years and moved up to Sheffield from Derby to live with her boyfriend’s family after moving there with her mum from Slovakia almost a decade ago. “Back home it’s so hard with money and for the kids,” she tells me. “Here there are better paid jobs and schools. They have a better life here so usually they want to stay.”

Further up the street, a man leaning over his car while looking at his phone provides me with a useful lesson in not judging a book by its cover, as Martina Pokutova would have it. If you were being uncharitable you might say this man has the demeanour of someone who wouldn’t look out of place cast as a heavy in a mob movie. However, as we talk it becomes clear that what he is reading on his phone is the Bible.

He doesn’t want to give me his name or have his photo taken, but is happy to tell me he’s 42 and came to Sheffield 11 years ago in 2012. He gets a bit grumpy with me when I ask about well-publicised problems in the area like litter or fighting, and says rather than drinking or smoking, he practises Christianity. He’s a member of the Apostolic church, an offshoot of the Pentecostal church, a denomination that has a large presence in the city’s Roma community.

Like David Kandrac, the man is originally from Bystrany, but he never goes back. He has four children, all of whom attend one of the two schools in Fir Vale. And his job prospects are also far better here than in Slovakia, both because of the discrimination he would face back home and the larger size of the UK economy. “I can’t work back home,” he tells me. “My country is small. Here is much bigger.”

It’s a refrain I’ve heard time and time again in Page Hall. Sheffield’s small Roma population have — to a man, woman and child — come here for a better life. Just like the vast majority of migrants have always done before them, all over the world. Mark Payne agrees with Gulnaz Hussain that the community is more settled than ever now and there is no chance of large numbers of them suddenly deciding to move back to Slovakia. “Their lives are so much better here,” he tells me. “Why would they?”

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.