After the Blitz, there was the rubble and the remains. The remains were worse than the rubble: there were no guarantees that the roofs of those remaining buildings wouldn’t fall in and kill those lucky enough to have survived two World Wars. So many of the remaining structures were razed to the ground. What is a city minus its buildings? A collective force of will, maybe. Sheffield had to imagine itself from the ground up. White-knuckle itself back into existence.

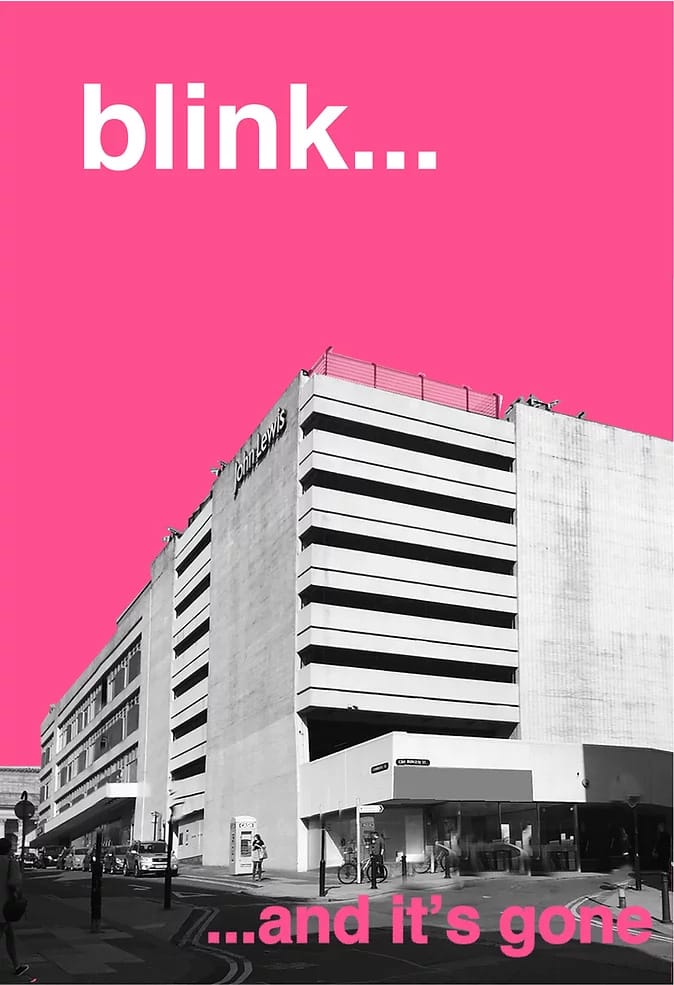

Part of that collective re-imagining was Cole Brothers, which was built along modernist lines: form follows function. It is a purpose-built department store and as such, not intended to be beautiful, though some people persist in finding it so, anyway. A somewhat larger proportion of Sheffielders think it’s ugly. This was clear enough from the responses to Historic England’s decision to list the building in August. Sheffield MP Clive Betts declared it an eyesore. Nancy Fielder, the former editor of The Star, went one further, pronouncing it a “truly ugly building”. The day after the building was listed, the newspaper’s front page splash delivered a one-word verdict: “Ludicrous”.

But rewind six decades and things look remarkably different. For the Sheffielders of the 1960s, along with housing projects like Park Hill, and Gleadless Valley, and the Castle Market, Cole Brothers was an expression of the optimism of the time. When it opened on 17 September 1963, hundreds of people crammed into the store on the first day, eager to set their eyes on Sheffield’s new shopping palace.

For many in the city it was where they worked. At Cole Brothers and then later John Lewis, three generations of some families were employed there. It wasn't perfect, the building's central escalators were constantly breaking down. But despite the drawbacks, when the closure was announced, old employees who hadn’t seen each other for years talked about their sadness at its demise.

And for customers, many of them women, department stores represented something else: freedom. Historic England’s listing recognises not only the architectural and heritage value of Cole Brothers, but also the social and cultural values. According to academic Susie L. Steinbach in her book Understanding the Victorians, while scholars are divided on the question of how liberating shopping was for Victorian women, some argue that “consumerism was inherently liberating and helped women to achieve public authority.” She’s clear on one point though: “new forms of consumption allowed suburban middle-class women new access to the public realm—”. But as Steinbach reports, for some women, this access to certain public spaces only emphasised how little access they had to others, with suffragettes breaking the plate glass windows of Liberty’s, Marshall & Snelgrove and other shops on Oxford and Regents Street in 1912 to demand “access to another public realm, that of politics”.

Regardless, Victorian and Edwardian women finally had a place in the public realm. These department stores prospered in the decades that followed by providing a place where women could feel a sense of well-being and relaxation (which perhaps goes some way to explain the weirdly gendered feeling of the layout of many department stores to this day, with items that might typically appeal to men — like electronics — on one floor and items which might typically appeal to women — like fragrances — on another).

For me, it’s just always been there. A great hulking mass of concrete, glass and tile rudely plonked right slap bang in the middle of the city: a part of Sheffield. I’m not really a big shopper but I would go to John Lewis. It was where I would look for birthday cards and presents. The top floor electronics department was always fun to browse for things I couldn’t afford. I also bought an eclectic range of items from there when I moved into my flat at Park Hill, from pots and pans to a deckchair for my balcony.

While Historic England doesn’t list buildings on aesthetics alone, not everyone thinks it is ugly. The store was designed by Yorke Rosenberg Mardall, an architectural firm responsible for projects including St Thomas’s Hospital in London, Gatwick Airport and Manchester Magistrates’ Court. The building is derided as a “concrete box” by some, but not everyone agrees. On their website, the Twentieth Century Society says the building is “notable for its strong proportions” and “clear, crisp lines”. This is further emphasised by YRM’s signature tiles, which were used not only to keep the facade clean but were also a reference to buildings iconic brutalist architect Le Corbusier had designed across Europe including his Armée de Salut in Paris.

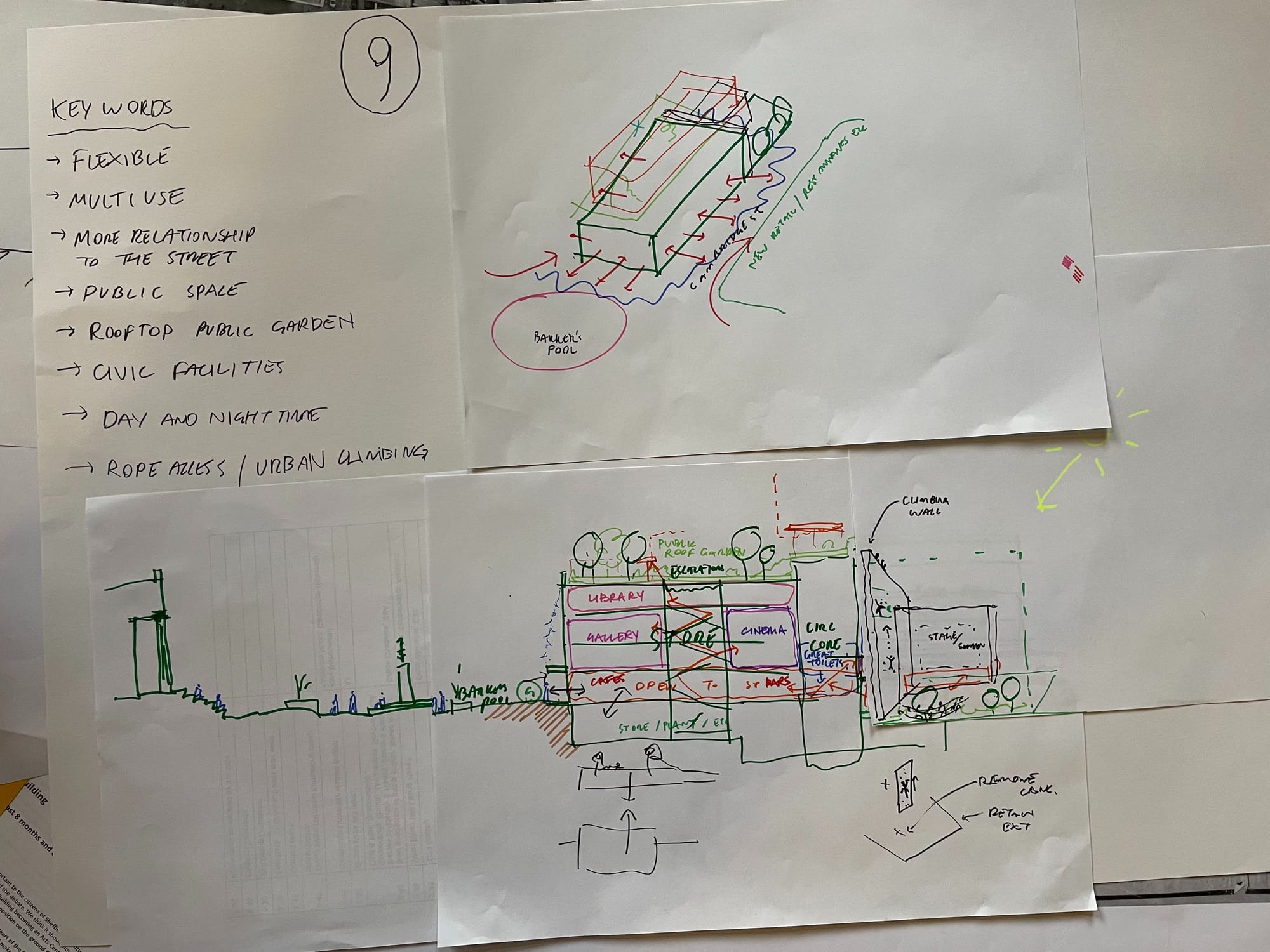

Last week, the Sheffield Society of Architects and Sheffield Civic Trust held a “design charrette” at Channing Hall on Surrey Street (a charrette, for those like me who didn’t know, is a “public meeting or workshop devoted to a concerted effort to solve a problem or plan the design of something”). The event attracted around 100 people from a wide range of different disciplines and backgrounds. These included architects, councillors, heritage experts, engineers, university lecturers, businesspeople, residents of Sheffield — and even lowly journalists. The session was billed as an “afternoon of creative collaboration” where people could bounce ideas off one another. Nothing was off the table, even demolition. “Some on our table wanted to blow Cole Brothers up,” one group said. “But they have been persuaded to change their minds.”

Since its controversial listing last month, it seems that everyone in the city has weighed in on what to do with the building. But it’s important to understand what listing means. A common misconception is that listing means nothing can happen to the building. But listed buildings are changed all the time and some even get demolished. In Sheffield, both Park Hill and Castle House were listed and have gone on to be hugely successful redevelopment projects. As Simon Gedye from the Sheffield Civic Trust said: “Just because something is listed doesn’t mean it can’t be altered successfully”.

These questions are not just pertinent in Sheffield. Lots of department stores closed down in the pandemic and some are under threat of demolition, the most famous being the Marks and Spencer store at Marble Arch in West London, which dates back to 1929. As a result, the Twentieth Century Society has recently launched a campaign to protect them as important parts of the country’s heritage.

Two recent examples show how department stores are being reimagined. In Hull, the famous Hammonds department store has been transformed into a food hall which opened last year, while plans to convert Knight & Lee in Southsea (also formerly a John Lewis store) into a hotel, cinema, bar and gym have recently been approved by Portsmouth City Council. Coco Whittaker from the Twentieth Century Society said there was no reason that Cole Brothers couldn’t have a similarly bright future. “It is a remarkable building which can definitely be repurposed,” she told us. “We think this building has massive potential.”

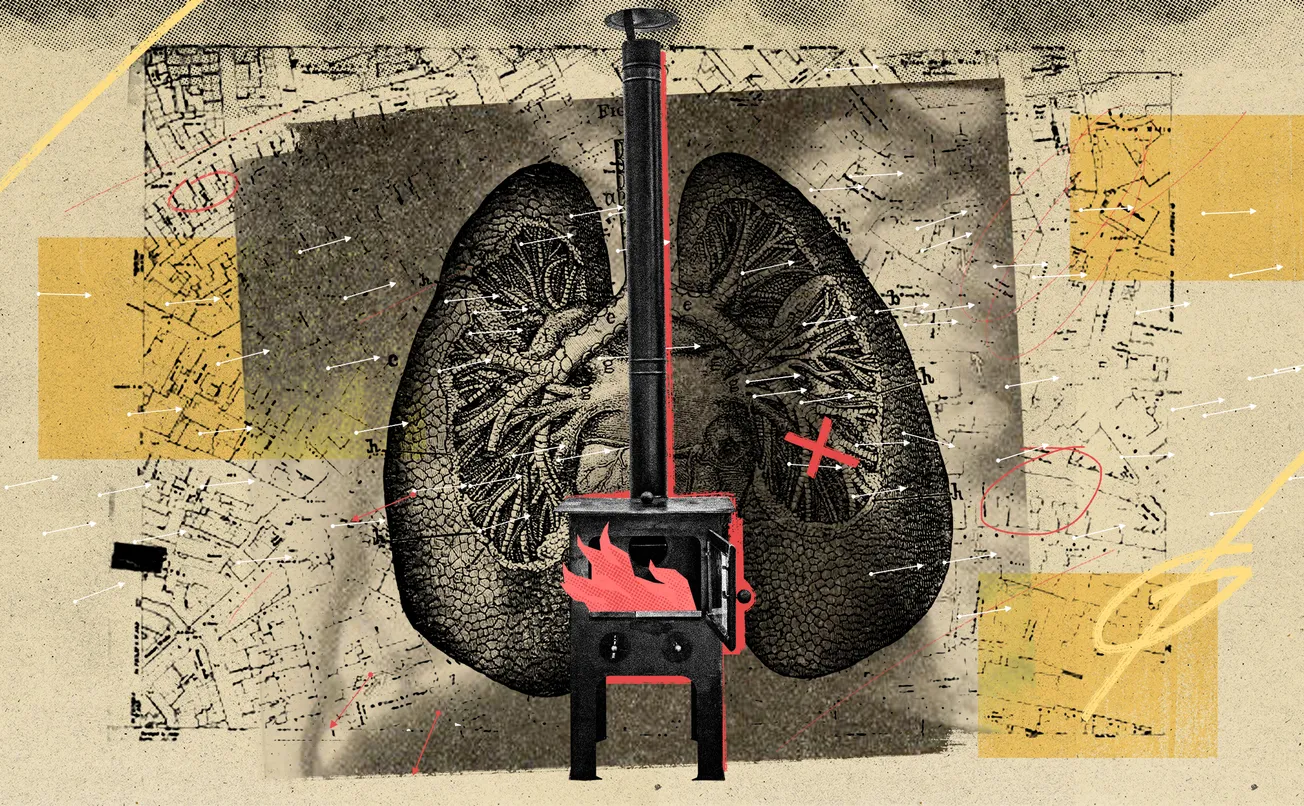

And then there is the environmental perspective. The climate emergency is here to stay — and while swerving building demolition might not sound like a huge way of combatting it, many would disagree. In late May this year, the Commons Environmental Audit Committee chairman Philip Dunne said that “our buildings have a significant amount of locked-in carbon, which is wasted each time they get knocked down to be rebuilt, a process which produces yet more emissions.” So many huge concrete buildings in Sheffield have been razed to the ground over the last 30 years (Hyde Park, Kelvin and Norfolk Park flats and the Castle Market, to name just four). Could these structures not have been repurposed instead?

None of which is to say that any of this is easy and there aren’t major issues with renovating these buildings. Department stores tend by their nature to be large structures with deep floor plans (meaning the centre is a long way from the edge and natural light can be hard to come by). This can sometimes be resolved by creating atriums — but would this be seen as changing the building too much?

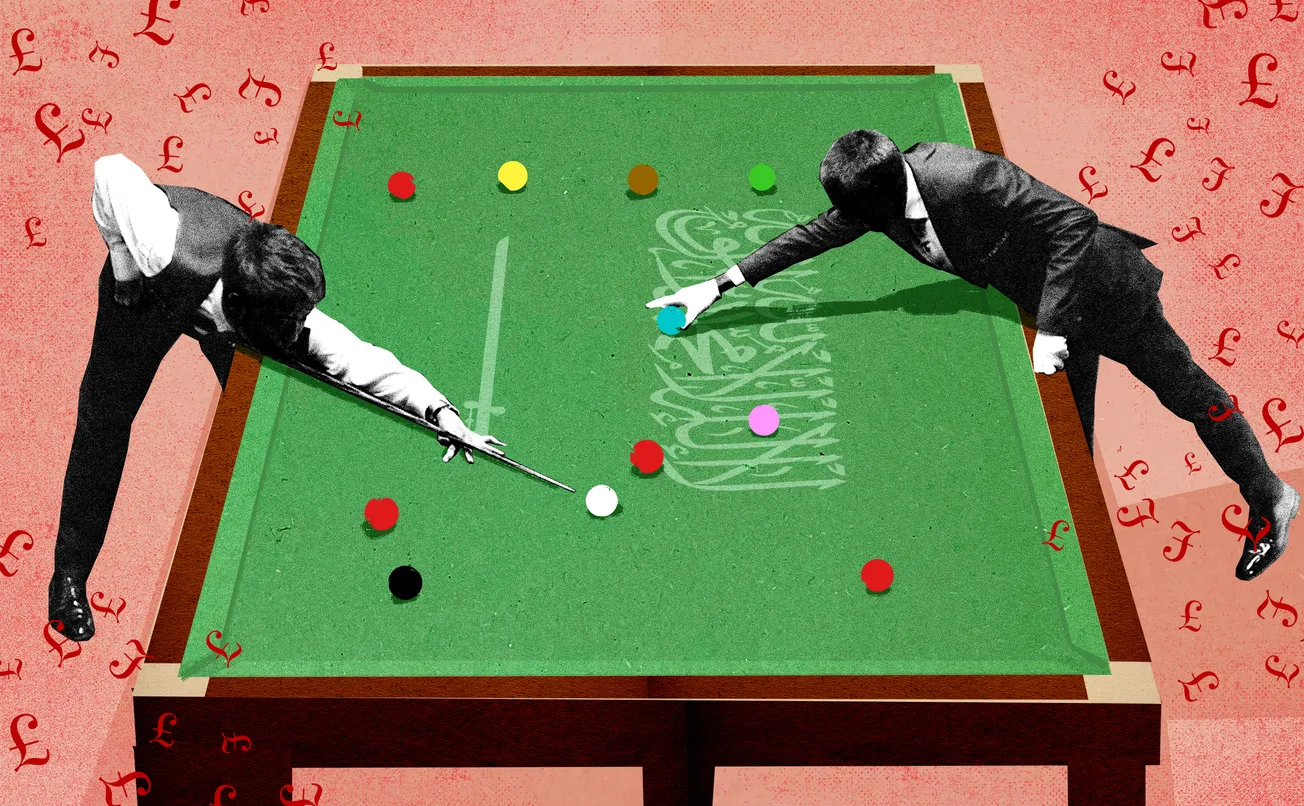

And where would the money come from? According to city councillor Mazher Iqbal, who attended the charrette, the cost of refurbishment of the building is around £40m. In an age of never-ending austerity, how likely is it that Sheffield City Council will be able to find that kind of money? And if the funding comes from private sources, what would they want in return?

During the five-hour session, so many ideas were suggested for what to do with the building it’s difficult to remember them all. But certain key themes emerged. At the end, when groups were called on to present their ideas to the meeting, almost all suggested that the building would be an ideal as a new home for the Graves Gallery and Central Library. Their current home on Surrey Street was built in the 1930s and as a result wheelchair access is far from ideal. In a bigger home, some suggested the Graves Gallery would be able to show more of its vast collection off at the same time while the library may also be able to accommodate the archives which are currently down on Shoreham Street.

Several people on my table likened this idea to a European-style “Kulturhaus”, a civic space which brings the arts together under one roof. An art gallery on one floor, a library and archives on another, a performance space on a third. Another suggestion which seemed to have a lot of support was a public roof garden, repurposing the former staff area into a chic cafe or trendy bar overlooking Barker’s Pool.

While it might have been battered by online shopping over the last ten years, in-person retail isn't quite dead yet. Many people still want to hold something in their hands before they buy it or try on a piece of clothing without going through the rigmarole of returns. Could some element of retail be retained as a way of paying homage to the building’s initial purpose? “There is a burning desire to bring new uses to this building,” said Elizabeth Motley from the Sheffield Society of Architects. “But we shouldn’t forget that its original function was retail.”

Some of the groups ran with this idea. One suggested the bottom floor should retain a place for perfume concessions, evoking the department store tradition of walking through a fog of different scents in order to get to the rest of the store. Others suggested opening up the building with shopping arcades running the length and breadth of the store featuring independent traders and makers’ spaces. Could the idea of window displays also be kept? One person remembered Cole Brothers’ windows as “an art form in their own right”, especially at Christmas.

Some ideas were a bit more imaginative. One group suggested using the building's car park as a skateboarding centre while another thought its rear facade could be made into a climbing wall. The car park’s similarity to the Guggenheim museum in New York led to one group suggesting it too could become an art gallery — although this may have been a joke.

During the meeting it was claimed by several people that Sheffield has a “really good record” of repurposing its heritage buildings. Many would think that this is at least debatable. While there are obviously some high-profile successes such as Park Hill and Castle House, many other 20th century buildings have been demolished and other, older buildings have been left to rot (the Old Town Hall and Salvation Army Citadel). What future awaits Cole Brothers, only time will tell. But one thing we’re not short of are ideas for what to do with it.

For me, it’s a no brainer. The Graves Gallery and Central Library desperately need a new home, as do the city archives. To bring these together in a repurposed Cole Brothers would be a fitting legacy for a building that has been a key part of our city for the last 60 years. A Kulturhaus for Sheffield, right in the heart of the city.

There will be no briefing this Monday due to the Queen’s funeral — and after that I am taking a few days off so we will be running a reduced publishing schedule. But we’ll be back to normal next Saturday, 24 September with a weekend read that is out of this world.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.