By Dan Hayes

“We’re looking for Stop the War,” say two women carrying a Bradford and Shipley TUC banner. It’s shortly before noon outside Sheffield Town Hall on Saturday, 25 February, and I’m here to report on a protest against the new Clean Air Zone, two days before the controversial scheme is due to begin. But a protest by the Stop the War Coalition against Western involvement in the war in Ukraine has been organised for the same time in the same place. The potential for confusion is delicious.

Finally confident I’ve found the right protest, I get out my notebook. The crowd is about 50 strong when I get there, but swells to about 100 after 10 minutes. It’s full of mainly very normal looking Sheffielders, making the one man dressed in a steampunk outfit stand out a little bit. Confused looking Chinese students walk through with anti-CAZ leaflets freshly thrust into their hands. But some people walking past are certainly in agreement with those protesting. “I’m with ‘em,” says one woman as she walks past me.

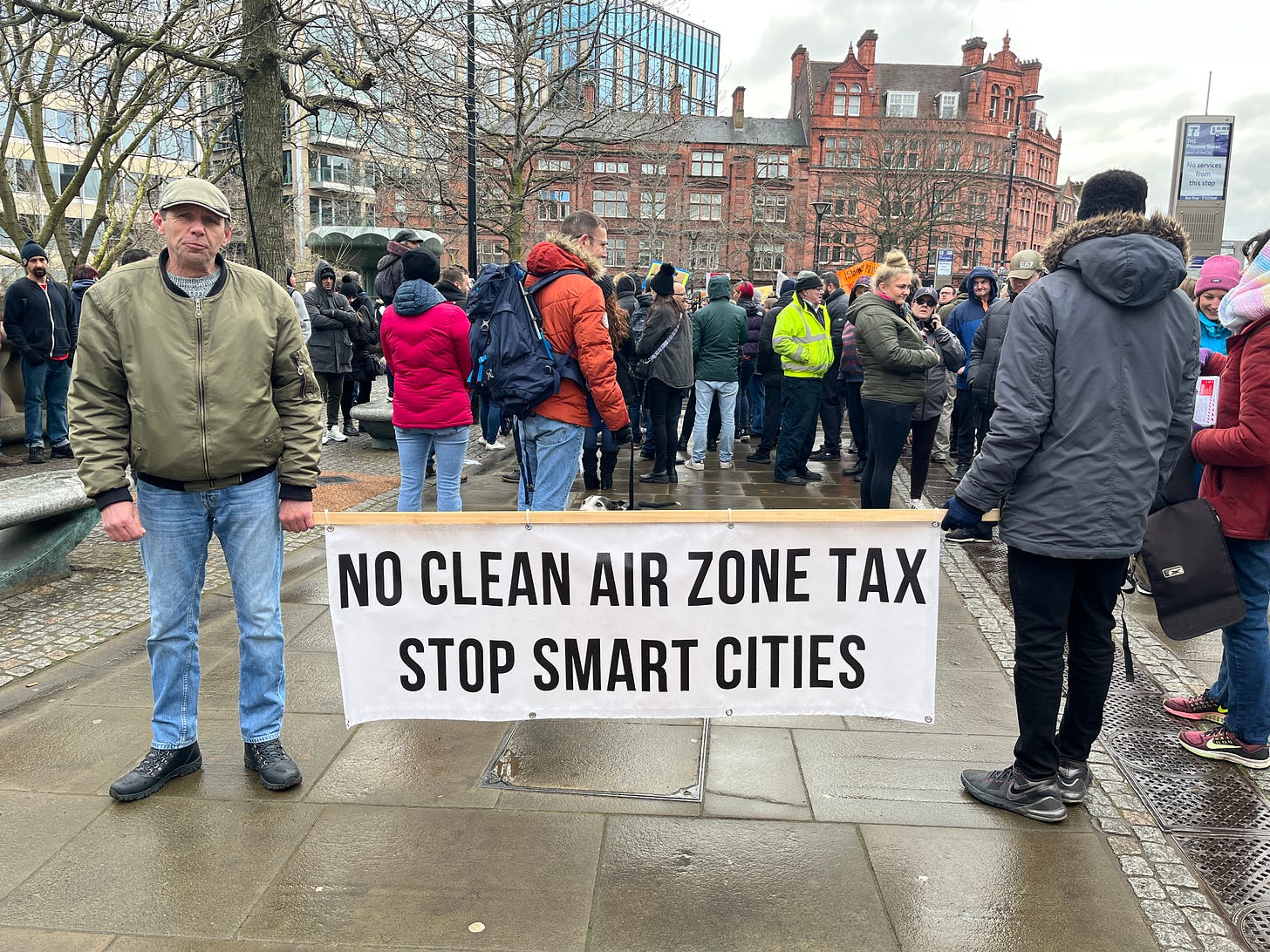

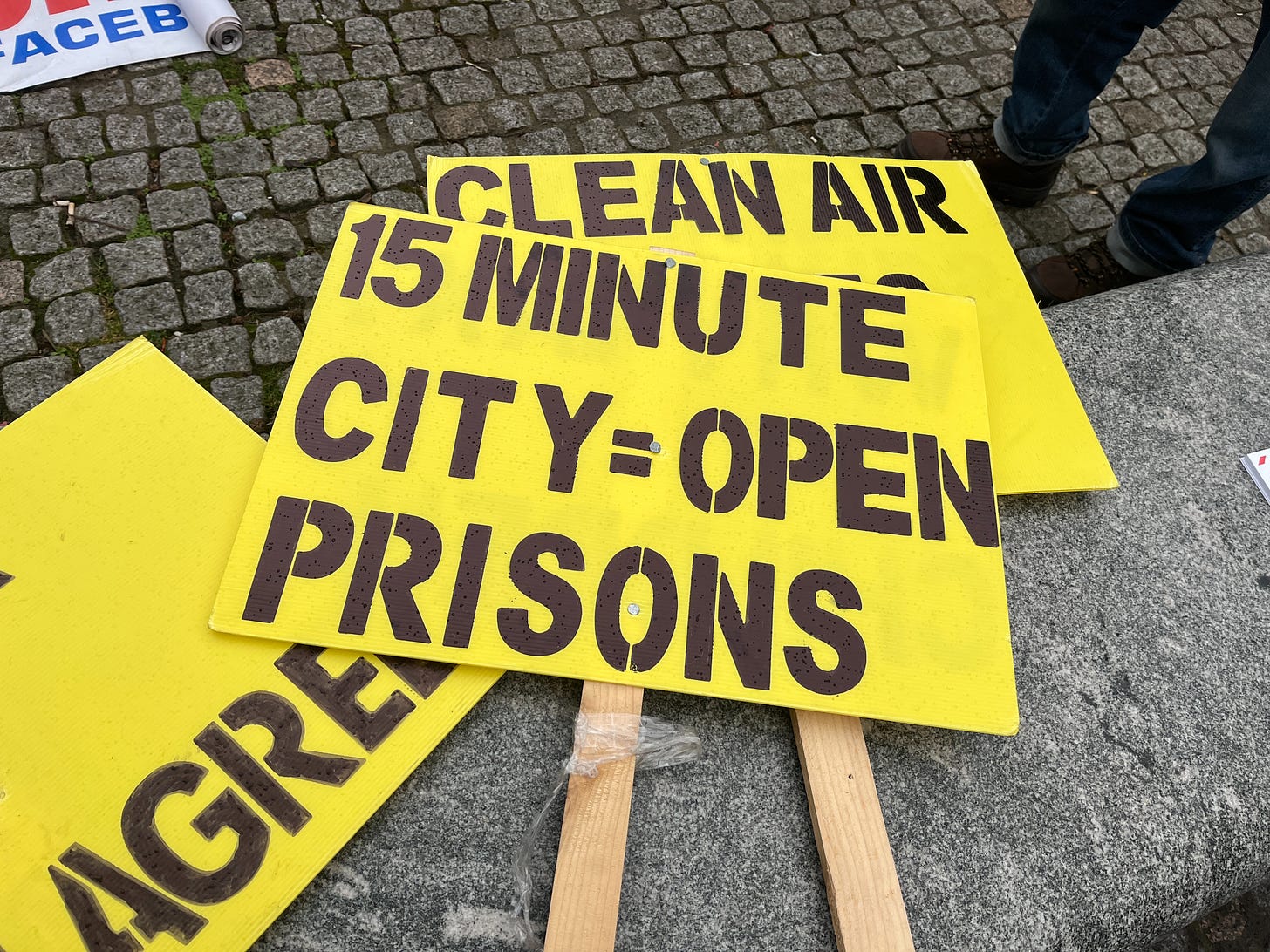

Walking around I take a look at some of the banners people have brought with them. As well as a host of anti-CAZ placards, there are quite a few others that seem to indicate the CAZ is just one concern among many. A huge white tarpaulin strengthened with balsa wood is the biggest I can find. “No clean air zone tax,” it reads in block capitals. “Stop smart cities”. Another reads “15-minute city? Clock off WEF” while a third reads “15-minute city = Open prisons.”

If I hadn’t been following the now 6,000-strong Sheffield anti-CAZ Facebook group I probably wouldn't know what many of these terms mean. But according to some of those who post there, CAZs are merely a prelude to much bigger changes in the future. While they may be dressed up in the language of convenience, “smart cities” and “15-minute neighbourhoods” are really an attempt to keep us locked down in our own neighbourhoods. The WEF or World Economic Forum are the sinister cabal from Switzerland imposing these nefarious ideas on a mid-sized city in Yorkshire.

One of those present at the protest is Matthew Betts. He set up the first anti-CAZ Facebook group in his home city of Bradford in 2022, and has since gone on to seed the idea in many of the other cities which are planning to follow suit. He’s clear that he’s here to protest the CAZ, but he is willing to talk about 15-minute neighbourhoods as well, if a little wary. Why, I ask. “Because you get classed as a conspiracy theorist,” he tells me.

We have a nice chat. He’s prepared to concede that they sound like a good idea. But he has concerns. “Are we going to be able to offer everybody the same?” he asks. By Betts’s logic, if Sheffield was divided into however many 15-minute neighbourhoods, who would guarantee there would be, for example, a cinema and a swimming pool in each one? “People also have different choices for supermarkets,” he continues. “I like Morrisons and this lady might like Lidl. Is there going to be one of each in each area?”

But as well as these practical concerns, there are also darker worries about where all this might lead. Like many others in the vast array of Facebook groups that have been set up to warn people of the dangers of 15-minute neighbourhoods, he fears the CAZ is a seed from which much more draconian plans could grow. Once you have an ANPR system (automatic number plate recognition) in place, Betts says it gives councils many more powers which can be progressively ratcheted up if required. According to the Facebook group, people’s fears range from the sensible-sounding (councils exploiting them to make money) to the frankly bizarre (governments using them as a way to create vast “open prisons” which people aren’t allowed to enter or leave).

Much of the online opposition references proposals in Oxford and Canterbury which are currently being consulted on. In both cities, the councils have proposed dividing them into zones which would limit people’s ability to drive — but not walk — between certain areas of the city at certain times of day. The Oxford scheme proposes limiting drivers to 100 free journeys between zones every year, after which they would have to pay. The Canterbury scheme would require drivers to use the outer ring road rather than drive through the city. For many, the ideas feel like too much power is being given to the state at the expense of individuals. Already in Oxford, irate residents have vandalised and destroyed new traffic bollards to allow their cars to pass through.

After about half an hour we get to the part every wedding guest dreads: speeches. Some make their points better than others. One young man tells the crowd he is about to become a father for the first time. He has a lockup within the CAZ which he has now been priced out of because he can’t afford to change his van. He says he is now relocating to Prince of Wales Road, adding both time and cost to his commute. His speech ends to thunderous applause.

Next up is a nurse, who comes across less well. Her lengthy speech assails the Clean Air Zone as an unjust scam, yes. But it’s also a rambling and incoherent rant against Covid vaccines, lockdowns, 15-minute neighbourhoods, and just for good measure the entire theory of man-made climate change. “Does this feel like control?” she asks the crowd at one point. “It does to me.” Halfway through her speech, it starts sleeting.

For many critics, these concerns are predicated on a misunderstanding. Rather than restricting people’s choices, 15-minute neighbourhoods are about providing services nearer to where they live, so they don’t need to travel to the other side of Sheffield to go to the supermarket, for example. The idea comes from European cities, where many of the amenities people need on a daily basis are located nearer to where people live (the best example is supposedly Paris, where 94% of people live within five minutes of a boulangerie).

Like many things, ideas that seem new are in reality very old. In fact, the current furore only became a thing when someone in an office somewhere decided to call the ancient concept of having a nice place to live with amenities nearby a “15-minute neighbourhood”. A country village or market town of 100 or more years ago, say, had naturally evolved so people could buy food, meet their mates, go to the pub, take the kids to their grandparents, visit the apothecary and generally go about their daily lives by taking a short walk from their front door. The idea held on well into living memory: older Sheffielders still remember when they were kids the main purpose of owning a car was so their dad could take them to the seaside once a year.

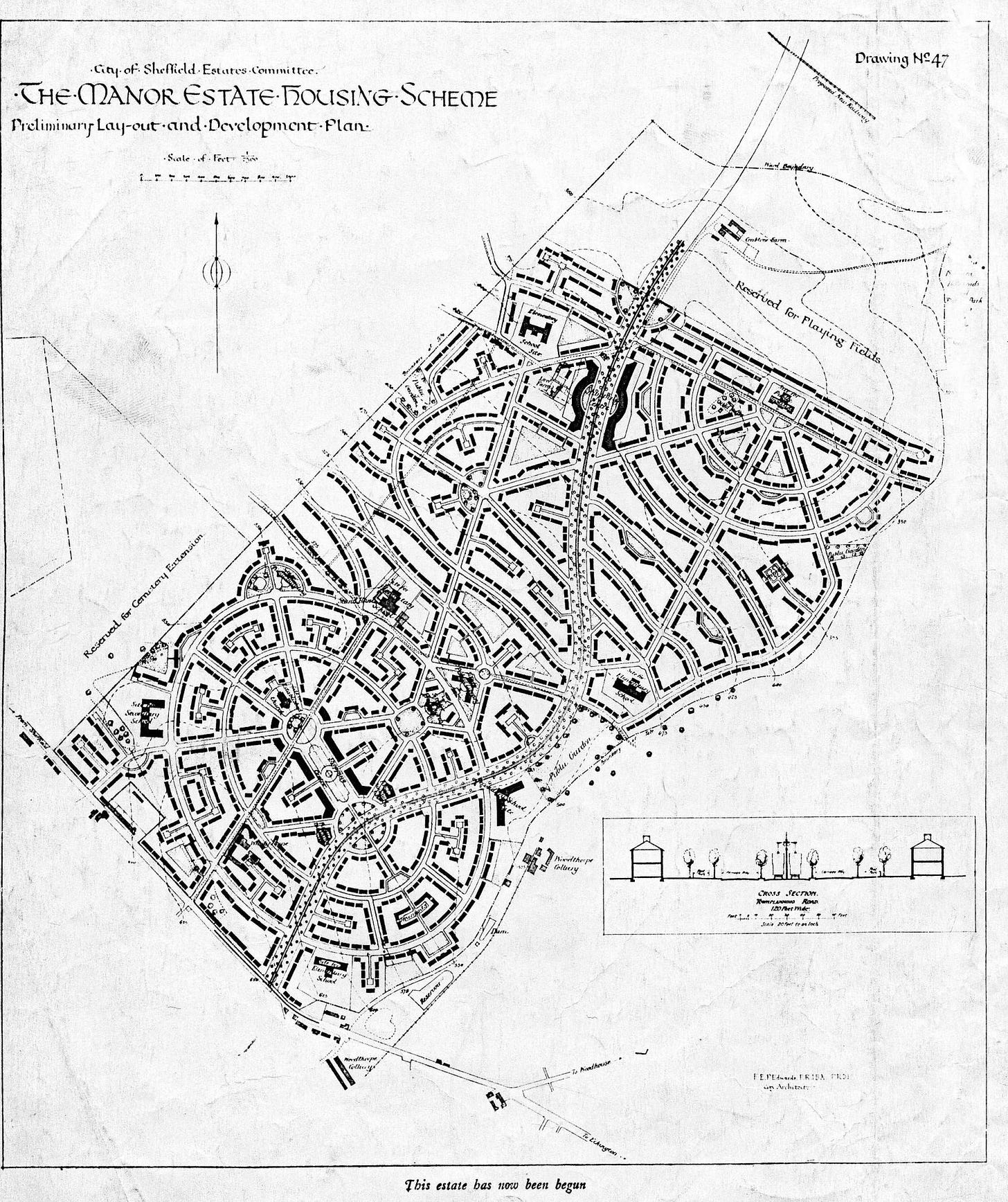

City council senior transport planner Paul Sullivan says a good example of a 15-minute neighbourhood is the council estate where he grew up 50 years ago. There his post-war counterparts had designed the streets and district centre so you could get everywhere you wanted to visit on foot. Head over to Parson Cross, Longley or Jordanthorpe and you can still see the remains of this idea in those estates’ central precincts surrounded by residential streets with schools, pubs, churches and playing fields all within easy walking distance.

But as the motorcar became affordable to ordinary people in the 20th century, planners jumped at the chance to build exciting new urban motorways. These drove folk out of their neighbourhoods and local shops on journeys which eventually led to the slightly less exciting giant malls, retail sheds and jobs an hour’s drive away in the current century.

Academics started noticing how draining neighbourhoods of their life via long and easy road journeys and poor public transport was making people inactive, unhealthy and isolated. And that’s why (cue: conspiracy theories) planners and politicians the world over began trying to make it easier for people to walk and cycle to go places, and (gulp) slightly less easy to get everywhere in a car.

Then a few months ago a trial of a low traffic neighbourhood scheme in Oxford became acrimonious as locals felt they would have to drive further to get across the city after a set of new bus and active travel filters went in. Someone in the local council’s planning department, evidently without a media strategist on their shoulder, decided to offer a travel permit for locals to drive through the gates 100 times a year, with a fine (like any other motorist) for transgressions beyond the 100 journey limit.

So local and national news outlets with an interest in outraged clickbait ran pieces about how freedom-loving motorists were about to be stopped by Soviet-style security guards as they tried to drive across Oxford, and angry social media groups formed to explore how the World Economic Forum are taking over our lives.

The issue for the planning world is that actually, yes, many urban professional academics think 15-minute neighbourhoods are a very good idea. And anyone can look up the works of Jane Jacobs in the 1960s and Jan Gehl in the 1990s and 2000s and find evidence to support the theory that woke professionals all over the world believe that driving less and walking more is good for us and our cities.

And yes, just like Paris with its local boulangeries, Sheffield is trying to follow this idea too, with 15-minute neighbourhoods very much part of the city’s local plan to improve health, cut pollution and reduce carbon emissions.

“It’s thinking about travelling a bit less,” says Paul Sullivan. “It’s not saying you can’t travel, but travelling less will make a bigger difference than switching your travel mode.”

Wil Stewart, director of investment, climate change and planning for Sheffield City Council, is prepared to stick his head above the parapet and admit this idea has always been part of his professional planning career.

“It’s not about restricting, it’s about adding more,” he tells me. “For me it’s about saying rather than having to get in your car to go to the shops or the dentist or to take your kids to school, you just walk there because it’s right there within a 10 or 15 minute walk.”

He says Hillsborough is a great example, where the district centre is a bustling thriving place, where people from surrounding areas walk down to get a coffee or a beer, visit the shops or go to a football match.

“Let’s see if we can get more of that,” he says. “It’s actually good town planning policy. In order to make people’s lives easier and better, we want to be able to provide the stuff that they need on a daily basis close to where they live. It’s as simple as that.”

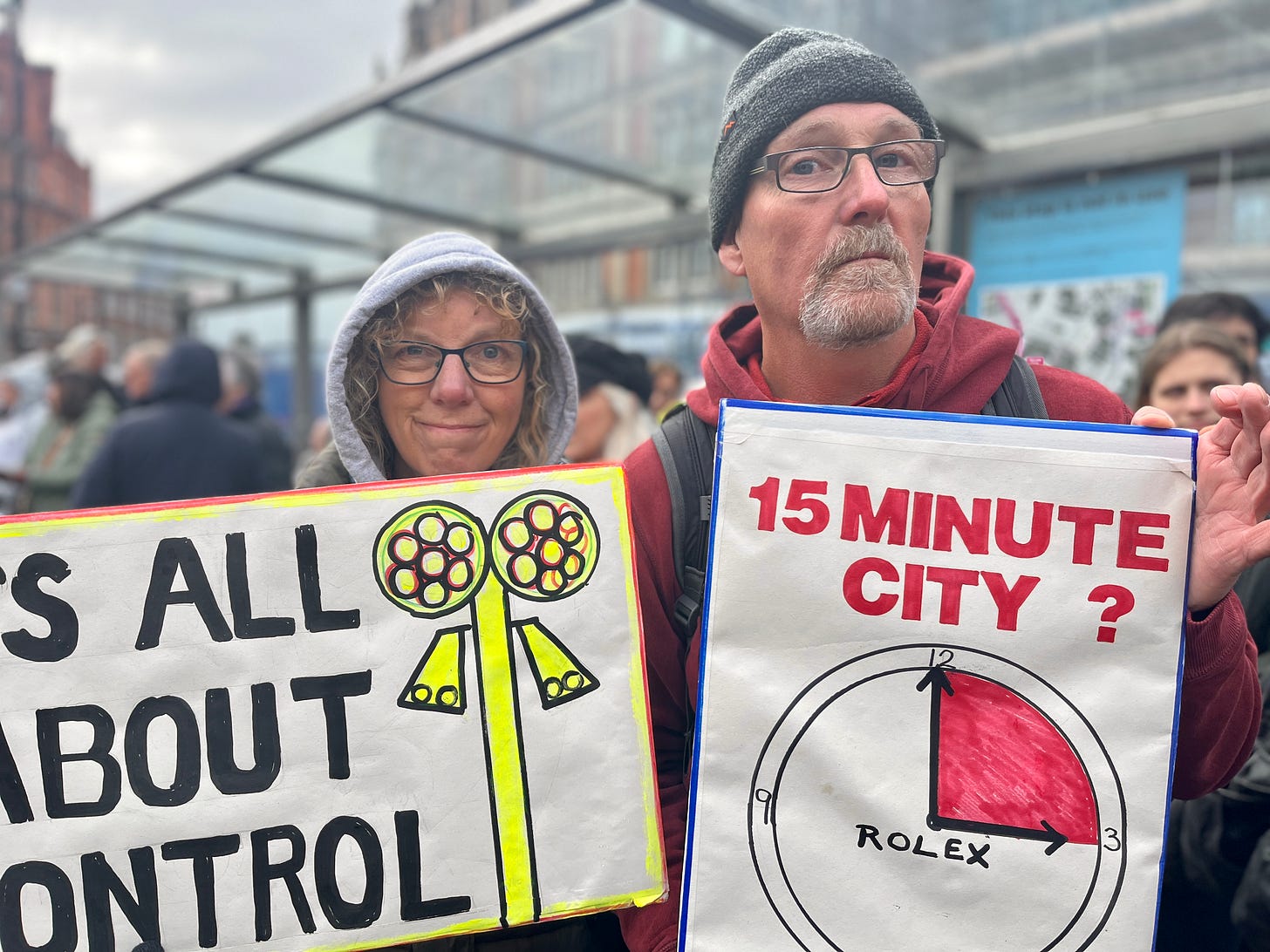

Back at the protest, I collar the man with the “Clock off WEF” placard. It turns out he’s there with his partner, who has a poster which has sinister-looking cameras on it. “It’s all about control,” it reads. They've come from Leeds today specifically to join the protest. As well as the CAZ, 15-minute neighbourhoods and the WEF, they are also worried about cameras on the streets and in supermarkets, the cashless society and biometric data capture.

Isn’t it just about having a doctor and a dentist nearby, I ask. “Dentist? Where I live in Leeds there aren’t any,” he scoffs. “People pull ‘em out with fucking pliers. Doctors say don’t bother coming today ‘cos we’re short staffed. They are offering us something they can’t deliver.”

To be honest, it’s a difficult point to argue with. Similarly, I have to agree with some of his ideas about public transport, if not his conclusion. “The easiest way to stop cars coming into town is to put more buses on,” he tells me. But here’s the point where we differ. The lack of buses isn’t about deregulation or 13 years of austerity, but about governments wanting ever more control of our daily lives. “It’s not about the climate,” he says. “It's about control.”

I disagree, needless to say, but then I would, because I’m a paid-up shill of the World Economic Forum and have a Bill Gates-made 5G microchip in my arm. Still, in an era when trust between government and the governed seems to be at an all-time low, nothing a random journalist says is ever going to change his mind. What are their names, I ask as I get ready to leave. They look at each other, suddenly wary of why I’m asking. “Just put us down as ‘freedom fighters’,” the man says.

Additional reporting by David Bocking

Re Dan's reply to Tanya:

Sorry, Dan, but the people who tell us to walk or cycle instead of drive rarely take disabilities into account. A recent opinion piece in the Star by the co-chairs of Sheffield Chamber's South Yorkshire Transport Forum, enthusing about 'active travel', announced that "walking to and from public transport stops can help physically inactive populations attain the recommended level of physical activity." No mention of the fact that a fair few physically inactive people don't have any choice in the matter!

The fifteen minute neighbourhood ideal seems to have been dreamed up by people who haven't walked the walk with anyone who has mobility problems. I've been living the 'fifteen minute neighbourhood life for almost twenty years. My local shops begin under a mile away from my home, along roads that are, for Walkley, remarkably flat. We are fortunate in having a library, shops, post office, hairdressers, barber, doctor, pharmacy, dentist, churches, pub and many other services along our 'high street'. So far, so good - a perfect fifteen minute neighbourhood.. But walking on to whichever premises I need adds another ten to fifteen minutes, and then I need to sit down and probably visit a toilet after doing my errands before tackling the (by then) half hour walk back home. I can't carry any substantial shopping, nor even wait for a bus because there are no seats at any of the bus stops on my route home. Walkley is a wonderful community, and I enjoy walking this route several times a week, seeing friends along the way and using my car only for heavy shopping. However, if I stop driving, or if walking a couple of miles becomes a problem, I will most likely switch to online shopping and risk becoming socially isolated. Unless public transport is improved and extended beyond recognition, the fifteen minute neighbourhood can only work for the physically fit.

I think this article misses the perspective of local businesses who are understandably feeling like there’s a potential threat from these types of schemes (and the recent red line proposals locally)?

Also, some of the feedback I’ve heard from Oxford has examples of families who are outside the different zones and people who have low paid work or who are carers and who have little choice but to make car journeys.

Encouragement and incentives are better than control and prohibition in my opinion