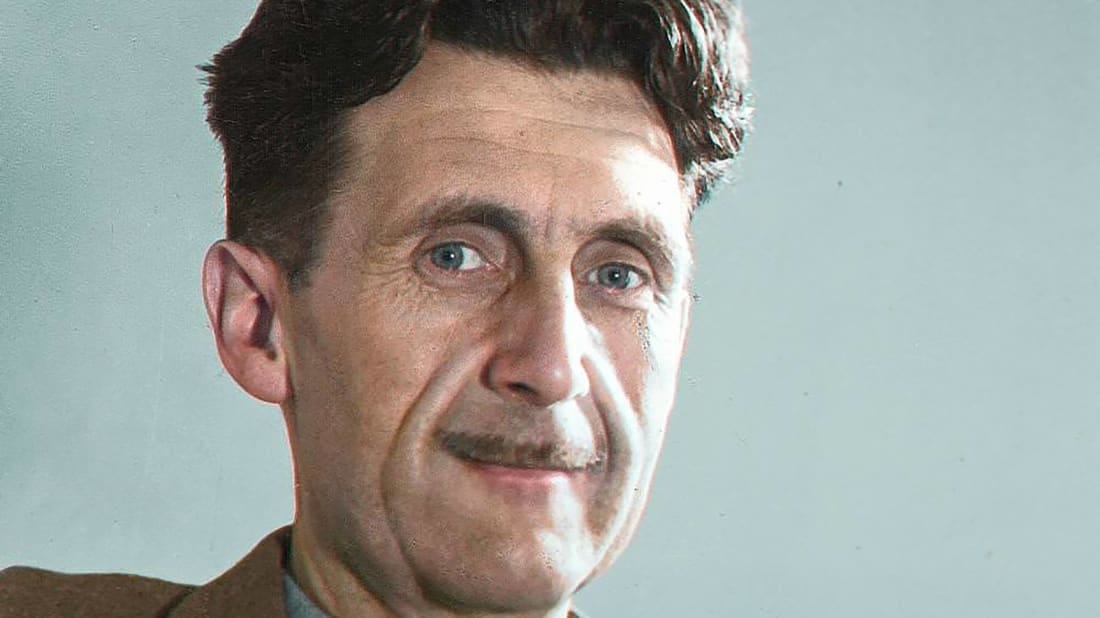

Is Sheffield the worst place on earth, a festering boil on the face of progress, civilization, decency? If you were to take George Orwell’s word for it, the answer would be a resounding yes. Orwell visited Sheffield for a few days in the spring of 1936 as part of his reporting trip to ‘the Distressed Areas’ of the North of England — a project embarked upon at publisher and social reformer Victor Gollancz’s suggestion — to gather material for what would become his non-fiction classic The Road to Wigan Pier. At the time, the 32-year-old writer, not yet famous and still earning a pittance for his novels, had never ventured further north than the Midlands before.

His first impressions, recorded in his diary at the time, are lyrical rather than damning: “Thick snow everywhere on the hills as I came along. Stone boundaries between the fields running across the snow like black piping across a white dress.” His first Sheffield diary entry is seeded with dream-like images: two rooks copulating “On the ground, not in a tree” (an image which was reworked into a safer “rooks treading,” in The Road to Wigan Pier after “rooks courting” was rejected by the publisher as being too explicit); huge piles of broken chocolate in cut-price confectioners’ windows.

A few days later, after exploring the city on foot and by tram, Orwell’s impressions curdle into revulsion. “It seems to me, by daylight, one of the most appalling places I have ever seen,” he writes in his diary. “In whichever direction you look you see the same landscape of monstrous chimneys pouring forth smoke which is sometimes black and sometimes of a rosy tint said to be due to sulphur.” He notes that all the buildings are blackened within a year or two of being put up, he’s never seen so many broken windows in his whole life, that he can constantly smell sulphur in the air. Plus: “I doubt whether there are any architecturally decent buildings in the town.”

What’s funny is that none of this is sugarcoated much: there’s very little difference in tone between Orwell’s book and the writing done for his own private consumption. Sheffield first appears in The Road to Wigan Pier as a byword for degradation: “Towns like Leeds and Sheffield have scores of thousands of ‘back to back’ houses which are all of a condemned type but will remain standing for decades.”

What I enjoy about these diary entries and the parts of The Road to Wigan Pier about Sheffield, is how unique Orwell’s distaste for the city feels. It doesn’t feel like contempt, exactly: it’s not an upper-middle class person making a largely working-class city seem smaller or ridiculous. There’s a real sense of awe entrenched in his hatred, with Sheffield seeming majestic in its ugliness to Orwell. He writes:

“At night, when you cannot see the hideous shapes of the houses and the blackness of everything, a town like Sheffield assumes a kind of sinister magnificence. Sometimes the drifts of smoke are rosy with sulphur, and serrated flames, like circular saws, squeeze themselves out from beneath the cowls of the foundry chimneys. Through the open doors of foundries you see fiery serpents of iron being hauled to and fro by redlit boys, and you hear the whizz and thump of steam hammers and the scream of the iron under the blow.”

I ask Orwell’s biographer D.J. Taylor via phone why he thinks the city provoked such a strong reaction in Orwell. “I think the sight of Sheffield — at some point he counts 33 furnaces or something like that — is a real eye-opener because he's never seen anything like this before.” He continues, “He's seen squalor, he's seen poverty, because he's seen it in Burma and Paris, where he's lived in conditions of considerable poverty, but he's never actually seen English people living in these kinds of conditions and he's never seen this level of industrialisation.” Taylor also alludes to an aspect of Orwell I’d never heard of before: his sense of smell, which he calls “one of the most highly developed things about him.” He argues that a bad smell could really impact Orwell and that this is obvious in his descriptions of life up north — a fact which goes some way to explain his focus on Sheffield’s sulphur smell, which appears both in the diaries and The Road to Wigan Pier.

Besides Orwell’s fascination with the city’s ugliness at that point in time, another striking aspect is its almost anthropological tone — composed as if he were reporting from an alien planet. It’s hard to imagine going to any location in the UK and writing about the state of the typical house there as Orwell does in The Road to Wigan Pier: “Sink in living-room. Top floor has no door but gives on open stairs. Walls in living-room slightly damp, walls in top rooms coming to pieces and oozing damp on all sides. House is so dark that light has to be kept burning all day.”

This quality which might seem strange to a modern-day reader — English journalists writing about England as if exploring a foreign land — was relatively typical for the time, Taylor tells me. He calls the 1930s the era of the Southern middle-class journalist going north to investigate conditions, but also says the decade marked the first years of working-class writing being read in the South: “Sometimes it comes across as a kind of slumming, you know: how curious, how odd, these lifestyles are, but a lot of these were genuine voyages of exploration to find out what was going on elsewhere in England.”

He attributes this to an appetite on the part of the middle-class book-reading public to hear about these places, something he argues was historically rooted: by 1936, the Great Depression had been dragging on for several years. “Down in the South, the North had suddenly arrived on people's doorsteps: there were hunger marches coming down from Jarrow, it was not something you could ignore.”

The North had already arrived on Orwell’s own doorstep long before the trip, Taylor points out: prior to The Road to Wigan Pier, he had shared a flat in London with a friend of his, Yorkshireman and experimental novelist Rayner Heppenstall. “I think Orwell was rather fed up of Heppenstall boasting about how wonderful the North was.” This is woven through the book.

One of the great joys of the Sheffield extract of The Road to Wigan Pier (and the diaries) is Orwell’s character assassination of what Taylor calls “professional Northerners” — those who made their geographical origin the cornerstone of their entire identity, a practice Orwell clearly regards as both embarrassing and intellectually lazy. Orwell is caustic about what he calls northern snobbishness: “A Yorkshireman in the South will always take care to let you know that he regards you as an inferior.” He continues, “If you ask him why, he will explain that it is only in the North that life is ‘real’ life, that the industrial work done “in the North is the only ‘real’ work, that the North is inhabited by ‘real’ people, the South merely by rentiers and their parasites.”

In one of The Road To Wigan Pier’s most gorgeous moments, Orwell goes on to write that “feelings of this kind, which are the result of tradition, are not affected by visible facts… I remember a weedy little Yorkshireman who would almost certainly have run away if a fox-terrier had snapped at him, telling me that in the South of England he felt ‘like a wild invader’.” Taylor argues this was very clearly a reaction to Heppenstall and describes these moments as “the South getting its own back” as well as what’s palpable in the text: Orwell having a lot of fun with the stereotypical idea of the tough Northerner.

We also see this in the diaries in a description of one of the people Orwell meets in Sheffield: James Brown, a disabled man born with a malformed hand and foot, traits he fears would be passed on if he had a child, and as such who refuses to marry. Enjoyably, Brown believes that any genuine socialist must nurture a “feeling of hatred for the bourgeoisie, even personal hatred of individuals,” but Orwell calls him a “good fellow” despite this.

Orwell describes him as possessing the “usual local patriotism of the Yorkshireman” and riffs on how much of his conversation centres on comparing Sheffield with London, the better to denigrate the latter, with Brown arguing Sheffield is superior to the capital in everything — “eg. on the one hand the new housing schemes in Sheffield are immensely superior, and on the other hand the Sheffield slums are more squalid than anything London can show.” This is funny and something Orwell clearly thinks is a habit native to the city — even Sheffield’s worst qualities are something to show off about, if they are worse than London. There’s a delicious zinger on this topic in The Road to Wigan Pier: “Sheffield, I suppose, could justly claim to be called the ugliest town in the Old World: its inhabitants, who want it to be preeminent in everything, very likely do make that claim for it.”

But Orwell also seems to have a lot of affection for the people he meets there. He stays with a couple, the Searles (“I have seldom met people with more natural decency. They were as kind to me as anyone could possibly be”) and he meticulously notes down Mrs Searle’s recipe for fruit loaf, step by step, in his diaries. Brown shows him round and even though Orwell has offered to pay for all his meals, always goes out of his way to find cheap places to eat and to spare the writer any expense. While Brown claims to hate the bourgeoisie, Orwell argues he treats him as a sort of honorary proletarian because of his interest in Brown’s city.

But this isn’t to say things are entirely friction-free during Orwell’s time with the Searles. In his diaries, we learn that Orwell sparks an argument one night by — of all things — helping Mrs Searles with the washing up, something both Mr Searles and Mr Brown (who lives as a lodger in the Searles’ house) disapprove of. Mrs Searles sheds some light on the animosity, explaining to Orwell that in the North, working-class men “never offered any courtesies to women,” which she translates as women doing all the housework on their own, even when their partner is unemployed, “and it is always the man who sits in the comfortable chair.” She takes this situation for granted but doesn’t see why it shouldn’t change. Orwell observes that, “The man is practically always out of work, whereas the woman occasionally is working.” Yet women continue to do all the housework and the man nothing, save for carpentering and gardening. “I think it is instinctively felt by both sexes that the man would lose his manhood if, merely because he was out of work, he became a ‘Mary Ann.’”

This aligns with D.J. Taylor’s account of things. He argues that Orwell was, as in so many other parts of his life, a fish out of water up North. “They knew he was posh, he was a gentleman.” He references a moment in The Road To Wigan Pier where he’s listening to people rant away about the bourgeoisie and while he sympathises with them, he’s also sick of it. Orwell loses his temper and tells the person that he’s bourgeois and so are his parents and if he doesn’t shut up, he’s going to punch them in the head “or something like this — he was so annoyed.”

“In some ways, he’s very interested and curious,” Taylor tells me. “But in other ways, it’s often a rather uncomfortable thing to have to do. He’s really making an effort to fit in there.”

Orwell’s descriptions of Sheffield’s ugliness are the most amusing passages of his writing on the city. But less amusingly, what also emerges from the diaries and the book is the extent of the poverty that dominated the 1930s and how dominant misery and hunger was in the city. “In Sheffield I was taken to a public hall to listen to a lecture by a clergyman, and it was by a long way the silliest and worst-delivered lecture I have ever heard or ever expect to hear,” Orwell writes in the book. And then: “Yet the hall was thronged with unemployed men; they would have sat through far worse drivel for the sake of a warm place to shelter in.”