A quick reminder: as May comes to a close, this really is your last chance to take up the spring offer. Try being a member for less and get all of our reporting with no annoying paywalls. Plus, know that you are buying into reader-supported local news: the only alternative to clickbait.

“Running through the landscape there are picturesque streams supporting their own little ecosystems… there are lots of different grasslands… you’ve got hares and herds of deer…” Michaela Strachan is waxing lyrical about the huge range of habitats and wildlife found in one of Sheffield’s favourite spots: the Longshaw Estate. It’s home to such a rich variety of nature that the BBC have chosen the site for Springwatch’s 20th birthday.

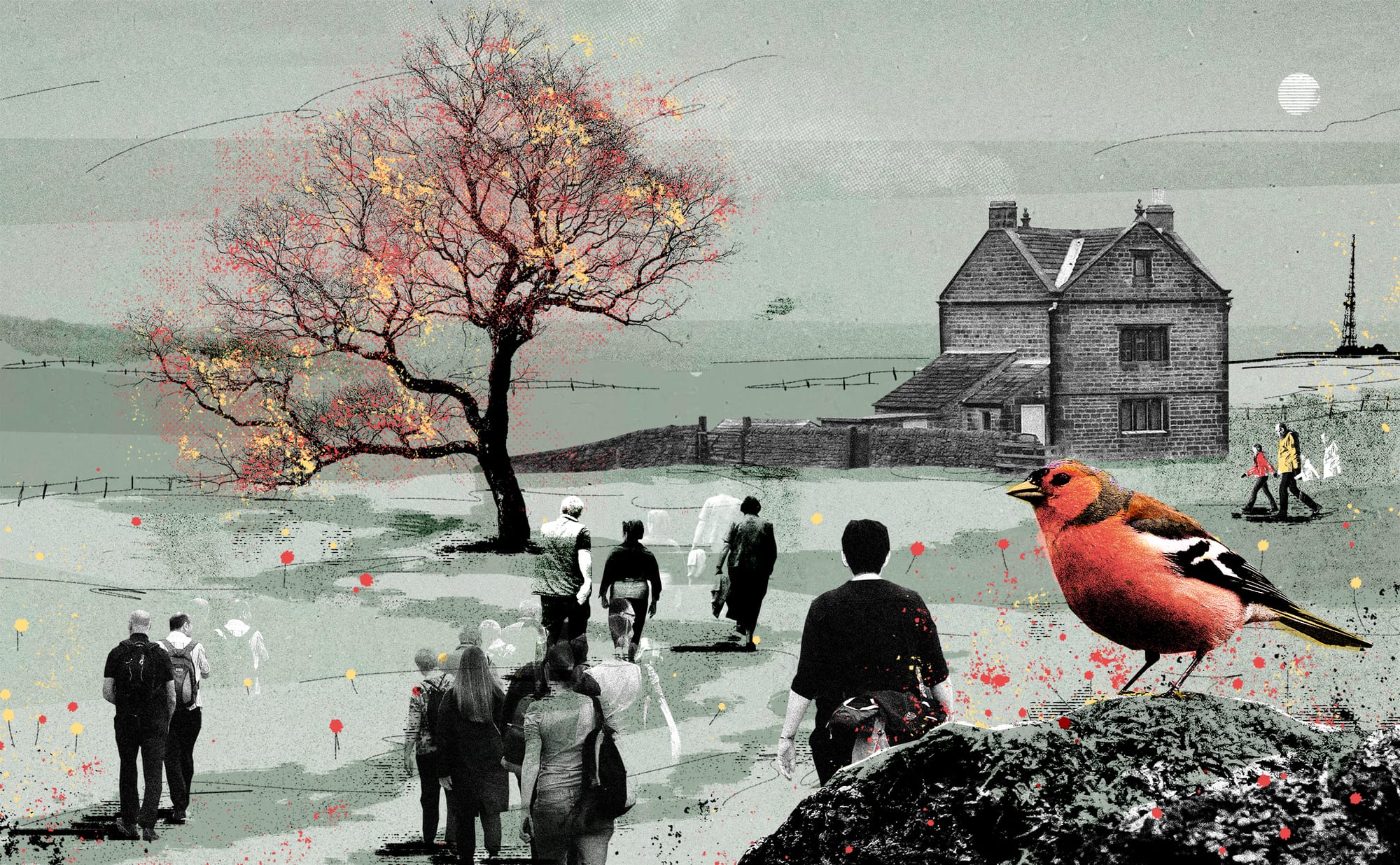

But leave the Springwatch yurt behind for a moment, cross the Derbyshire border on Hathersage Road into Sheffield and head out across the (now) damp moor of Burbage to Carl Wark if you really want to understand where the Longshaw story starts.

Your trail shoes will be flecked with peat by the time you climb the heights of what may or may not be a 3,000 year old Iron Age Hillfort. The square blocks of Longshaw Lodge are in plain sight, possibly because the fabulously wealthy Duke of Rutland felt a wild hilltop of ancient masonry like Carl Wark would be an ideal view for his mates when he built Longshaw 200 years ago.

If you’ve made your ascent at the weekend, the rocks of Burbage Edge will be laced with climbers, while gaudy fell runners pick their way over the top. Electric mountain bikers or sleek gravel riders will be trundling up and down the trail – once the Duke’s Green Drive, where he’d take his fellow aristocrats on carriage rides to see the ancient mysteries he now owned, before the menfolk lubricated themselves up for a few days of grouse shooting.

Historians have no sure idea of what happened on this hilltop long before shotguns or crampons existed. Maybe it was an occasional fortification or livestock market, possibly a sacred site for rituals we can only imagine. Look at the size of the carefully placed wall stones and you can’t help wondering who was working here, sharing the valley with wolves and arrow-bristling enemies.

Strachan and Chris Packham will be telling us about badgers, pied flycatchers, dragonflies and owls with long and short ears, all wonderful creatures to find on the edges of our city. But talk to any ecologist or countryside manager, and you’ll know that the wild moorland landscape to be featured on Springwatch this year is really a habitat of humans.

Ancient people hunted here, then farmers and villagers used the moors for livestock, tending bracken for bedding, gathering wood for tools and fires. After that, enclosures excluded the commoners and reserved the land for shooting, as volunteer historian for the National Trust, Thelma Griffiths, told me in preparation for a pre-Covid exhibition about the ‘People’s History’ of the estate.

She found newspaper reports of 1886 telling how two gamekeepers hurled a local woman over a wall for bilberry picking on Houndkirk’s shooting land. Then in 1903, we have a strange set of photos showing the Earl of Bradford bracing his gun in suggestive fashion watched by a female companion squatting in the heather, and then firing alarmingly over the head of his young loader at a fleeing grouse; you can imagine the grouse chortling at his poor marksmanship. And ‘Game Bag’ records show that over 4,300 birds were blasted from the sky here in the top influencer’s leisure pursuit of 1925.

The terrible impact of the First World War (along with debts and death duties) meant the 100 year leisure shooting experiment had run its course on the moors around Longshaw. The estate and surrounding packages of land were put up for sale in the 1920s so the Duke of the time could concentrate on some of his grander houses. It was snapped up by the Sheffield local authority, with all sorts of possibilities mooted: a new reservoir, housing, a hotel or even a golf club.

But a public appeal led by campaigners Ethel Gallimore (later Ethel Haythornthwaite) and rambling lobbyist GHB Ward said the land should be used as a post-war refuge for the smoke-ridden populations of Sheffield. They raised £14,000 to buy the estate, with scores of local people donating as little as a few shillings. The land was then handed over to the young National Trust organisation, who’ve tended to Longshaw ever since.

“There was a general feeling that this was something worth doing,” Griffiths told me, “that life for the working people in the town was not good, that people really did need this land.”

Longshaw became a walking landscape for factory workers escaping the smoke, and then climbers in vests and plimsolls arrived to hone their skills on Burbage Edge. Meanwhile, rangers and conservationists from the National Trust began the long and evolving process of balancing the not always complementary demands of wildlife, landscape and people from nearby towns and cities.

Heavy sheep grazing and then grouse moor management helped dry out the moors from the wet morass navigated by the ancient people of Carl Wark. Rain and air pollution from the once-thriving factories of Manchester and Sheffield didn’t help. And then the changing weather, and the crash in many insect, bird and wildlife populations added new urgency to conservation work.

Over the years I’ve met staff from Longshaw and the Eastern Moors Partnership finding ways to restore and wild up a landscape damaged by human history, and now scorched and occasionally drenched by extreme weather. Rangers showed me how the mix of woodland trees like oak, birch and rowan and meadows at Longshaw is an ancient landscape called wood pasture, which is more attractive to rarer birds like flycatchers, one of this year’s Springwatch stars.

Planting sphagnum moss and dam building to restore peatland helps reduce carbon emissions and the risk of flooding, and improves water quality by filtering out peat sediment before it reaches reservoirs. It also allows natural moorland plants like bilberry and cotton grass to gain a foothold from the dominance of former grouse moor heather, bringing in new wildlife like dragonflies, wading birds, and lizards.

But restoring wild landscapes needs resources and people, to thin the trees now and again, to plant the moss, build the paths and clear the litter. And this week, after 15 years of funding cuts, the Peak District National Park Authority floated a controversial idea. If the government doesn’t restore the financial means of looking after our national parks, chief executive Phil Mulligan said, they may have to consider charging an entrance fee, as in America. While not quite a return to the days when commoners were bundled over walls, even a small charge would run counter to the traditional open to all ethos of the UK's first national park. (Longshaw, and its conservation efforts, are managed by the National Trust, and have different funding streams from membership, car parking and cafes.)

The old joke about Longshaw was that yes, it’s great that this wonderful landscape was secured for the working people of Sheffield to enjoy, to give them relief from their gruelling jobs and fresh air, away from the grime and soot of Sheffield. So why is the cafe always full of well-heeled people who look as if they’ve just rocked up from Dore or Hunters Bar?

The crazy days of lockdown helped change all of that. New people discovered Houndkirk and the Burbage Valley when the country was allowed to get out every day during furlough time, and many found Longshaw too, when it opened again.

The population at the much extended Longshaw cafe is now more representative and I hear the increase of visitors after Covid has continued. But how many of these new visitors read the countryside code, I was asked by one veteran ranger.

Dogs run round Burbage as their owners don’t know any different, I was told, and partygoers watch videos of Peak District sunsets then drive over from Derby or Birmingham to build a campfire for their own revelry backdrop. Despite the recent rain, a layer of damp ground will soon dry out into a severe fire risk again when the sun returns.

And new paths appear where runners and walkers and bikers find a shortcut, and leave a trail of degrading open peat that might soon need tens of thousands of pounds worth of slab repairs.

Craig Best, General Manager at the National Trust in the Peak District said he hoped Springwatch will inspire viewers to get involved with caring for the area, by supporting conservation work “or by making sure they leave no trace when they visit.” Sharing information about the importance of dogs on leads during ground nesting bird season, and raising the profile of unusual local species will give viewers a greater insight into why protecting this special landscape is so important, he added.

But there’s another uncomfortable truth — that putting Longshaw front and centre for the 20th anniversary of one of the BBC’s most popular programmes may, if anything, drive up visitor numbers further. They will come with the best of intentions. But wildfires begin with people whether they intend a blaze or not. Erosion and litter and scaring or destroying hidden nesting birds are caused by visitors. And the numbers are growing, while the money to manage their impact is shrinking.

Like the Gary Lineker of wildlife programming, Chris Packham is known for sharing his views. Will these pressures — and what to do about them — get a mention on Springwatch? Maybe — but unlike some of the easy steps we can take for nature (like installing swift bricks in new houses) the sheer weight of visitors is a knotty problem. After all, we want people to make the most of their hard won rights to the countryside. It's just tricky when so many do so in the same place, at the same time.

Read more from David Bocking about local nature on his website here.