It’s Tuesday morning, and the workers at Zurbiany are tidying the kitchen, legs of lamb and chicken slow cooking on the hob. The TV is providing ambient background noise, an Arabic-language news channel flickering between shots of a lush green farm and a newsroom. I’m sitting at a table texting a friend when Abdullah Al Hasmi, a chef originally from Aden in South Yemen, brings over a plate of zurbian, a tender lamb and rice dish cooked in saffron. There’s a bowl of spicy zhug sauce to season too, and maraq: soup made from lamb and chicken broth. It’s all delicious.

Many academic studies have been written about the Yemeni contribution to Sheffield’s economy and civic life. There have been documentaries, too: Thankyou, that’s all I knew in 1989, and the 2004 documentary Born in Yemen, Forged in Sheffield, both looking at the experiences of the 10,000 Yemenis who lived in Sheffield during the height of industrial steel production. But I want to understand what it’s like to be a Yemeni in Sheffield in 2025.

The simple version of the story focuses on the farmers who moved over in the 1950s and 1960s to find work in the steel industry, leaving behind sunny villages in the Yemeni mountains for Victorian terraces in Attercliffe and Small Heath. But the truth stretches back much further than that. According to From Ta'izz to Tyneside by Richard Lawless, in the late 19th century many Yemeni migrants moved to the north east coast to find work as seafarers. But a few decades later, the 1919 Aliens Restrictions Act made it harder for the British maritime industry to hire foreign workers to work on the ships. This forced these same migrants to find work on land, with many moving to cities to find work in the steel and transport industries.

Al Hasmi wasn’t among the sailors and steelworkers to move over during the late 19th and 20th centuries, but made his home in the UK in 2019. He moved to Runcorn; one day, while visiting friends originally from Aden, they asked him: “Why don’t you come to Sheffield?”

“Our community is here,” he remembers them saying. “We’ll help you, we’ll show you how to start in life.”

Al Hasmi took the leap. He moved to a leafy street in Crookesmoor, and enrolled in a government-funded English language course at Sheffield College. He was desperate to start working. “I don't want to get any benefit from the government,” he remembers thinking to himself. “They helped me enough. Now I want to try to find my way to stand up again.”

He is now a full-time chef at Zurbiany. Al Hasmi also helps cook itfars — meals Muslims eat to break their daily fast during the holy month of Ramadan — at mosques and community centres. He credits his work as a chef with enabling him to get to know people in Sheffield better: “When you are in the kitchen, you learn a lot of things about the people, even which food they like. Now, when I see any customer, I know how much food he likes, whether he likes dry rice or some masala rice, any big piece of meat or small piece. I was thinking that we are all the same, same food we are eating. But actually it's not.”

The iftars are attended by the Somali, Sudanese and Pakistani communities as well as the Yemenis; Al Hasmi notes that something that has struck him about Sheffield is the “mixed culture”. Maged Arishi, the 37-year-old owner of the Yemeni Restaurant, agrees. “On our street, we have Somalis, Sudanese, Iraqis, the Kurdish,” he says via phone call. “I think there’s a high collaboration between the communities in Sheffield, especially the Yemenis and Somalis and Pakistanis, and the Algerians and Iraqis.”

I ask around about other people I should meet and I keep hearing one name in particular: Dr Abdul Shaif, 64, the director of Aspiring Communities Together, a citizens advice organisation. Everyone knows Dr Shaif and seems to love him. He agrees to meet me in his office in Fir Vale, where we drink tea and chat about our lives in Sheffield.

Shaif and his mother moved to Sheffield in 1969, to join his father, who worked for British Steel for 23 years until the mass industrial redundancies beginning in 1978. He remembers his father coming home after working 70 hour weeks, with dermatitis all over his hands, burns from the furnace works and complaining of ringing in his ears. His colleagues didn’t teach him any English, so all he understood was the language of the steelworks: hammer, crane, furnace, sweep.

He recalls his father had dreams of coming to Sheffield to “make a lot of money in the steelworks and then build a castle back home so he can go and retire and live with me and my mum. But obviously that dream never materialised. He ended up dying in a council house and being buried here in Darnall.”

According to From Farms to Foundries: Racism, Class and Resistance in the Life-Stories of Yemeni Former-Steelworkers in Sheffield by Kevin Searle, Yemeni steelworkers were consistently paid the lowest wages and offered the least desirable jobs in the steel industry, compared to “a relatively mobile white middle class”. They also sustained a high level of injuries, with a 1989 occupational health project finding that one in seven Yemeni former steelworkers suffered from tinnitus.

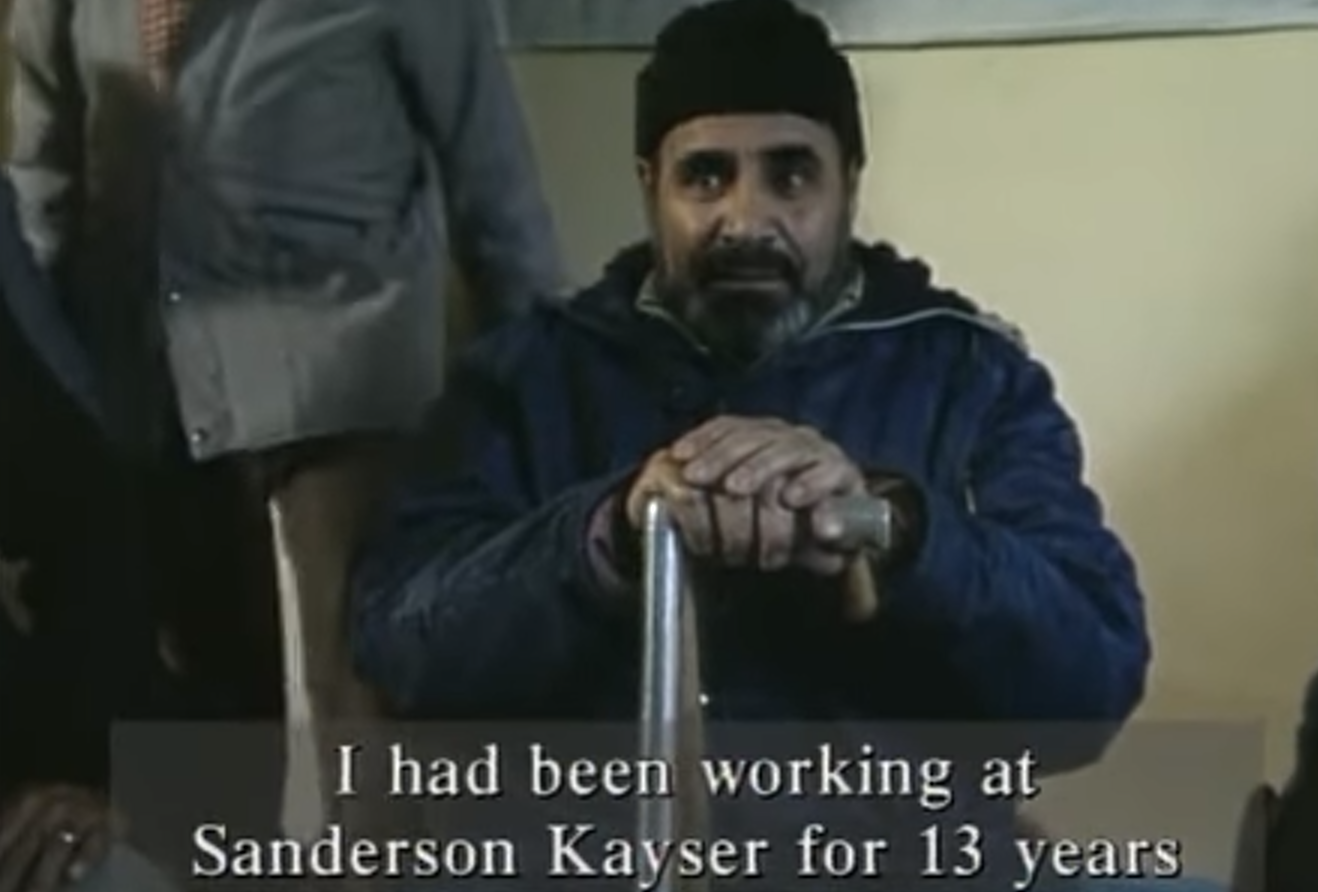

Screenshots from the 1989 documentary Thankyou, that’s all I knew by Sheffield Film Co-op.

Through Shaif’s work at Aspiring Communities Together – an organisation that tackles social and economic inequalities in black and ethnic minority communities in Sheffield – he often comes across former steelworkers. Their lingering injuries never fail to shock. “You know, when you look at their bodies, some people have holes here, holes here,” he says, pointing at different spots on his body. “And I think, ‘oh, my God, what did they have to go through?’ It always makes me upset because my dad had gone through that.”

How did they survive it? Shaif reflects for a moment, then says: “I think they were able to practice their religion, and maybe that's what kept them going. They had faith in Allah and they had faith in themselves.”

They also had the support of the community. In 1971, the Yemeni community clubbed together and raised £5,000 to buy 68 Burngreave Road to form a base for the steelworkers to unionise. The Yemeni Workers Union was born. Abdul’s own father contributed £10 to have a union that represented him, telling his son he felt as though the existing trade unions only seemed to support the white steelworkers. Every Ramadan after sunset, the community still gathers in the same house they collectively bought to break fast and share memories.

By 1986, there were no remaining Yemeni steelworkers for the union to represent, and the organisation, renamed the Yemeni Community Association (YCA), turned its attention to helping the struggling families of laid-off workers and securing compensation for those the most affected by industrial injuries. By 1990, 600 Yemenis had secured compensation for the diseases and accidents they suffered during their time working in the steelworks in Sheffield, thanks to the YCA.

Abtisam Mohamed, Labour MP for Sheffield Central, remembers as a child her dad would take her and her sister to the house on weekends to deliver clothes, toys and books for families experiencing the most hardship. I ask if it was these trips that made her realise the importance of collective action. She smiles at my lofty question, reminding me that she was just a child at the time and didn’t appreciate the purpose of the trips until recently, when she started asking her dad about why they were always going there. “I thought it was just me that was very political in the family,” she says, when we meet at Couch on Campo Lane. “I didn't realise that my father was also involved politically through a different struggle.”

If you’re enjoying reading this story, please consider joining us as a paid member of The Tribune. It’s so rare that journalists these days get time to speak to normal people and have an honest conversation about their lives, and at a time when so much local news coverage concerns itself with crime and violence, we wanted to shine a light on the ordinary lives of an extraordinary community of people. With our introductory offer, you can become a paid member for just £4.95 a month for your first three months – that’s £1.23 a week.

When Mohamed became MP, it was a huge moment for the whole community here, and back in Yemen. She was the UK's first ever Yemeni MP. She can readily recall the excitement she felt, and spent her first day fielding calls from news organisations across Yemen and the Gulf asking for interviews. "It feels really special," she says with a smile. "And I know that the community here in the UK feel very proud of that."

It was Shaif who gave Abtisam her first job, at Aspiring Communities Together. When I ask him about Mohamed's election, his eyes glisten with tears. “It's probably one of the proudest moments in my life,” he says. “Seeing her become a member of parliament made me feel that it will inspire so many others to see that it can be done.”

It’s getting dark and I have one place left to visit: Red Sea Cuisine on Spital Hill, a restaurant known for its famous lamb soup, which functions as a gathering place for the Yemeni community. Mohammed Alsadi, originally from Yafa'a in south Yemen, comes here most weeks to see friends and chat and practice for the legendary annual pool table championship.

A young father, Alsadi has a PhD in cloud computing, but is going through a rough patch. “I’ve had pitfalls in my life, so currently I'm not working,” he says. “I'm struggling with certain conditions, but hopefully I'm going back on track.” He spends most days reading about the growth of AI and hopes there may be a job for him in that field someday.

He also volunteers with the Yafa Council, a charitable organisation that helps Yemeni and Arabic speakers in Netherthorpe and Upperthorpe integrate into the community. Recently he had a new suggestion: that the volunteers should spend time with the elderly members of the Yemeni community who no longer have family around. “Most of them are left alone. No one visits them. So we have a regular visit, like once a month, and then we increase it to twice a month.”

The idea was borne out of a sense of loyalty to the Yemeni elders who he met when he first moved to Sheffield. Alsadi credits a man called Awaad, a retired steelworker originally from the same village, with helping him and his family understand their legacy. His family would visit Awaad every week until he passed away three years ago. It was his way of thanking him and other former steelworkers for how much they gave so that the next generation of Yemenis could have an easier life. And it was Awaad who helped Alsadi settle in, understand how to navigate the UK’s bureaucracy, find work and a place to live.

“It is hard starting up,” Alsadi says. “But whenever you have hard startups, you’re gonna have a bright ending.”

Additional reporting and photographs by Murtaza Rizvi.

Thanks for reading this edition of The Tribune. Putting people and their experiences at the centre of our writing is a core part of our approach, and we hope that you agree that it’s an important part of the service readers really need in an era of information super-abundance: shining a light on communities that aren’t often covered by local media. If you enjoyed this story and would like to receive more in your inbox, just sign up as a paying member by clicking the button below. With our introductory offer, it’s just £4.95 a month for your first three months – that’s just £1.23 a week.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.