Since we launched in 2021, the success of The Tribune has been astonishing. However, if we're going to carry on taking on the biggest investigations and commissioning great freelancers, we still need more paying members.

With our introductory offer, you get your first three months for just £4.95 a month. That's less than the cost of a pint for 16 newsletters packed full of original journalism and great cultural recommendations. Please join today.

Shortly after they got married in 2014, Dan Ashby and Lucy Taylor were looking at a big map of the world and deciding where to go. They were not, however, thinking about glitzy honeymoon destinations with crystal clear blue waters, or sipping cocktails on the beach. Instead, they were thinking about where they could begin a new life as a husband-and-wife journalist team.

“We did loads of phoning around different agencies to find out where they didn't have international freelancers and Tanzania kept coming up,” Taylor tells me. “So, we're like, great, we'll go there.” Ashby recalls: “We bought a camera, an editing laptop and a one-way ticket.” When they broke the news to Taylor’s mum, who is also a seasoned journalist, her reply was: “you'll come back with fewer limbs.”

Thankfully, they did return with their limbs fully intact and since 2020 Ashby and Taylor have been living in Sheffield and working as investigative journalists. They founded Smoke Trail Productions, producing a wide range of award-winning podcasts, radio shows and documentary films, about the environment.

Their BBC Radio 4 series, Buried, unearthed a deathbed confession from a truck driver about one of the worst environmental crimes in UK history: the illegal dumping of a million tonnes of waste near Derry, in Northern Ireland and its links to organised crime. For the follow up to that series, they teamed up with the actor Michael Sheen to investigate ‘Forever Chemicals’, specifically polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and how, despite being banned 40 years ago, they are still in our soil, food and even in our blood. Their most recent podcast series, Boy Wasted, traces how our recycling in the UK is ending up at illegal, and highly dangerous, centres in Turkey where Afghan refugees are dying in their hundreds due to unsafe and exploitative working conditions. What they uncovered was, according to Ashby, “a broken system full of criminality and death.”

Taylor and Ashby are currently so busy – the success of their ongoing investigative work means they are constantly receiving fresh leads and tip-offs – that, despite living in the same city, we have to settle for an 8pm Zoom call squeezed in at the end of a long working day. The pair met working on the student newspaper at York University in 2005. They quickly bonded over a desire to uncover stories and, as a driven and tenacious duo, they even set-up their own publication. “We got a bit hacked off with the student newspaper and wanted to start up our own independent website so we could have complete editorial freedom,” Ashby says, of founding The Yorker. “It was classic rebellious student stuff because the newspaper was owned by the Students’ Union, and the newspaper reported on the Students’ Union, so we felt we had to create a division of power.”

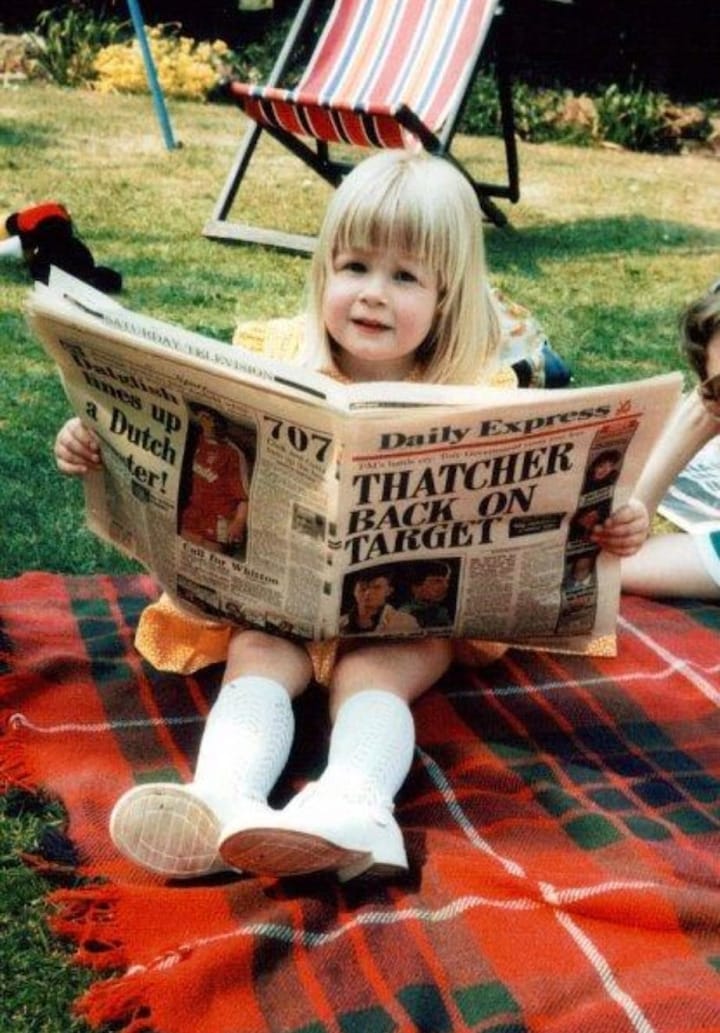

They both became motivated at a young age to go into this world. Taylor grew up in Sheffield and both her parents were journalists, working for the Sheffield Telegraph (when it was called Morning Telegraph) as well as for ITV. They even set up their own news agency in Sheffield, selling stories to national titles. “It’s like history repeating itself,” says Taylor. “We’re doing the modern day version.” Taylor recalls being surrounded by journalism as a child. “I think it's in my blood,” she says, while Ashby adds: “There are these amazing photos of Lucy as a toddler sitting on piles of newspapers, and her parents would be going off to door knock people on murder stories or reporting on disasters like Hillsborough.”

Ashby’s younger years were different but equally formative in guiding him towards the profession. With adventurous parents and a father in the merchant navy, they moved to South Africa when he was nine. “Before that, I probably would have had a very different life,” Ashby explains. “But growing up in Nelson Mandela's South Africa made me alive to issues, change, politics and all these things happening.” It was a work placement at 18 that sealed it for Ashby, though. “My first work experience was at the Cape Argus newspaper,” he says. “Which was this incredible anti-apartheid newspaper with all these hardened, old, grizzled reporters who'd been beaten up by the police but believed in bringing down apartheid. It was the most inspiring work experience placement. By the end of it, I knew that was it. I was hooked. I was going to be a journalist.”

The pair did a post-graduate course at Cardiff but gaining experience after that was hard work. “I was reading news bulletins for Heart Radio,” says Ashby. “I was doing every single graveyard shift that no one else would do just to earn £55. I would travel to Heart Swindon to read the 5am bulletin and actually lose money on the train, so I would camp to save money. I was desperately trying to get together a showreel and experience.”

They soon both landed work at ITV Tyne Tees at the same time. “ITV gave us contracts without realising that we were partners,” says Ashby. “It was the luckiest thing.” Their introduction to the place was full on. “We had an absolute baptism of fire,” says Taylor. Within their first six months, two of the most high-profile crimes that the region has ever encountered took place: Derrick Bird killed twelve people and injured eleven others in a shooting spree in Cumbria, followed by the famous manhunt for Raoul Moat after another shooting spree. “It was not only this awful story, with an extraordinary police hunt, but then for Paul Gascoigne to turn up at the scene offering chicken, we were thinking: ‘what the hell is going on?’” says Ashby. “Is this normal that ex-footballers have to solve crises? But the more serious point is that we got an amazing training in beat journalism, working a patch, doing crime, courts, door knocks, chasing down leads, working sources.”

And then came the decision to buy that one-way ticket, as it had been Ashby’s lifelong dream to return to Africa to be a journalist. It was this period when the pair found their true calling as investigative journalists covering the environment. “It really changed us,” says Ashby. “It was an amazing experience but at times a harrowing one. It was everything in extremes.”

Ashby wasn’t that interested in environmental stories before. “Having grown up in South Africa, I actually really didn't like them because a lot of them were about elephants,” he says. “And there's a resentment of that, because you want to talk about people, development and politics. But the irony is, we were there at this extraordinary time in the illegal ivory trade and we increasingly got swept up in investigating and reporting on that story. We realised it was a more important story than I had thought because it affected politics, government, and it corrupted the police. It was this huge economy.”

In particular, they were investigating British and American aid, which was being misdirected into poaching gangs. “There was a park called Ruaha where 10,000 elephants were killed, which is the biggest massacre of elephants that Africa has ever seen,” says Ashby. “And we wanted to expose how actually a lot of aid was fuelling the poaching.”

They worked with South African wildlife conservationist Wayne Lotter, who had set-up a task force to bring down ivory gangs. But one day in 2017, the extent of the danger involved in investigating these stories became tragically apparent. “Wayne was shot to death not far from where we lived, in Tanzania,” says Ashby. “We had spent the previous week with him, so it was this awful time where we had lost our friend.” However, they pressed on regardless. “We were slightly traumatised and grieving but we also had this big story to finish and we knew that Wayne would want it out,” says Ashby. “So we had a final few months in Tanzania where we were quite scared trying to finish the story. Eventually it was published on ITV News at 10 and then we were told that we couldn't go back to Tanzania.”

Their time in Africa had been eye opening in terms of seeing the impact of illegal activities on the environment, as they had also reported on dynamite fishing gangs blowing up coral reefs and rosewood trafficking. “What we witnessed was awful biodiversity loss and damage that was happening all over Africa,” says Ashby. “Once pristine beaches were destroyed by plastics and forests were being cut down. An experience like that is so formative that now I look back and think that's probably why we're still such committed environmental journalists.”

When I suggest they sound like a fearless pair, Taylor deadpans, “I don't know if we’re fearless or just a bit stupid”, before Ashby chips in to suggest it’s his other half that can lay claim to that title. “You're more fearless than me,” he turns to say to her. “When we got surrounded in the bush by men with guns, you were the one who was trying to secretly film them all the time.”

Being a married couple has been a huge advantage. “Because we have each other, you take more risks with your own life than you do with your partner’s,” says Ashby. “That was always something that made us safer.” And it’s also helped them land more scoops and gain access. Many trips in their years in Africa were disguised as travelling for their honeymoon. “We went on countless honeymoons,” laughs Ashby. “Honeymoons in Malawi, Zambia, all over the place. It allowed us access places that I think would be riskier for other people, particularly for, say, two big middle-aged blokes with cameras showing up.”

That said, Lotter's death was a wakeup call. “We were trying to keep ourselves really safe and we suddenly realised, if someone wanted to kill us, they just could,” says Taylor. “There's no way to protect yourself in that situation. And that's not just an African thing, it would be the same here. It just makes you realise your own vulnerability.”

In 2018, they left Africa in the peak of hot summer for Russia, in the middle of a brutally cold winter, where they worked as reporters in Moscow. “The regime accused us of being spies and made our lives a bit difficult and monitored us a lot,” says Ashby. “But largely, they left us alone.” They had also made a decision not to investigate certain areas that would be too dangerous. “Because of Wayne's death, we made a safety decision that we weren't going to publish stories about Putin's money,” Ashby says. “But what we were able to do was to report on the whole anti-Putin movement and be at these incredible protests with the likes of Navalny, who's now dead of course, and bear witness to what was going on – along with environment stories, which was still our passion.”

Like for many people, lockdown forced a change of circumstances and in 2020 they found themselves back in Sheffield to be around Taylor’s family. “We also wanted a new work challenge,” says Taylor. “We were itching to start doing the kind of things that we're doing now.” Despite growing up here, Taylor never imagined that doing this kind of journalism in the city would ever be possible. “I never thought I would be able to move back here, even though my parents were journalists here,” she says. “It just felt like that era was ending. When I graduated, local journalism was dying or was collapsing.” Circumstances and attitudes, along with the ease of more remote working, has changed that though. “It then just felt really possible,” she says. “And we found with the BBC that there's quite a lot of push to be out of London as well. So in some ways, it's an advantage not to be in London, business-wise, and obviously journalism-wise it is as well, because you are tapped into a whole different set of people, stories and perspectives. There've been lots of positives.”

Ashby echoes this too. “Because it's a much smaller creative and professional community than Manchester or London, it feels like people root for each other more. And there are a lot of environmentalists in Sheffield, so there is an advantage to being here. Professionally, we've probably never been happier in terms of doing really meaningful, fulfilling projects.”

For Ashby and Taylor – who have a bumper year ahead with huge projects planned across radio, television and books – investigating environmental stories right now is imperative. “We're at a really dangerous moment right now as we are beginning to see the rise of a climate denial movement the likes of which we haven't seen in 25 years,” says Ashby. “I never thought I would see that come back. It's a critical few years ahead of us but I find that audiences are really hungry and ready to change. There’s a huge motivation resource there. So us as storytellers, along with policymakers and lots of different people, have to find a way to crack this.”

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

If you enjoyed this great piece by Daniel Dylan Wray, and you want to get access to our fantastic subscriber-only stories this week, why not join up as a Tribune member today?

Our members have recently received this brilliant piece by David Bocking on why Broomhall should be a model for the Sheffield of the future, and this fascinating feature by Holly Williams about the small-but-perfectly-formed wonder that is the Lantern Theatre in Nether Edge.

As well as those, you also get access to our entire back catalogue of amazing stories and, better yet, you will be supporting our mission to give Sheffield the kind of in-depth reporting it deserves. With our introductory offer it costs just £4.95 a month for your first three months. Please join today.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Tribune and reach over 30,000 readers, you can get in touch or visit our advertising page below for more information

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.