I’ve spent a fortnight shadowing South Yorkshire’s mayor, Oliver Coppard. We’ve talked through every aspect of policy, but I still don’t understand where his motivation comes from. Why did he get into politics, I ask.

I’m expecting something along the lines of “to make a difference”, but he surprises me (not for the first time). He said it was realising that politicians could be human beings, something which happened when he met (then-MP) Andy Burnham. “It allowed me to think it was then something I could go on and do.”

Is it hard to stay human, with the pressure of the job? For the first time, Coppard doesn’t have a ready answer. “It’s something I’m kind of learning to do, I suppose,” he reflects, after a long pause. “Even now I can feel myself trying to work out what to say to you, rather than just giving you a human answer. And I… I don’t like that impulse, but you have to kind of learn it to a certain extent.”

I’m surprised by his frankness, but it seems to complete part of the picture of Coppard for me. In the convivial camaraderie of the combined authority offices, he’s right at home. But the public-facing part of the politician's role can be tough and requires a degree of fakery to survive. I don’t think it comes naturally to him.

My first meeting with Coppard takes place in the offices of the South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority (which he leads). When I arrive, I’m struck by how different these new mayoralties are to the old type. Instead of the wood panelling and deep pile carpets of a town hall, the office is glassy and modern. In emails from staff to set up meetings, it’s always “Oliver”, instead of “Mayor Coppard”. And when the lift doors open at the top floor, the vibe is more like a tech startup than any local authority I’ve come across. Aides are dressed down; one is even wearing a Hawaiian shirt, and it’s only a Monday. I expect to see a small dog at any moment.

In case you don’t breathlessly follow South Yorkshire politics, a quick recap on where we are. A devolution deal with “Sheffield City Region” was struck in 2015 as part of the government's northern powerhouse programme. It was meant to give Sheffield greater control over, among other things, transport budgets and strategic planning. Unfortunately, it has emphatically not been plain sailing since then. Several local authorities, including Chesterfield, essentially pulled out, with a court finding there had been insufficient consultation with residents. Dan Jarvis became the first “metro mayor”, but there was serious acrimony between the partners — with both Barnsley and Doncaster signing up for a “One Yorkshire” proposal in an attempted breakaway.

When the government made it clear this wouldn’t happen, internal negotiations continued, but it took another two years to get sign-off on a deal to actually release the powers and money South Yorkshire had been promised. Then Jarvis announced that he was stepping down, preferring to serve as an MP rather than a mayor. Enter Oliver Coppard, who won the mayoral post in 2022.

Coppard is Labour, born and bred, and was the party’s candidate in the Sheffield Hallam constituency in 2015. We’re covering him now as he’s been in the role just over a year, and is clearly growing in influence. With his friend and ally Tom Hunt leading Sheffield Council, Coppard is playing a bigger role in the city’s affairs — even, we’re told, being brought in to lead the negotiations around the new council Lib-Lab-Green pact.

He and Hunt are both exiles from the Jeremy Corbyn years, now brought back into the fold. Coppard, who is Jewish, did not contest Sheffield Hallam in 2019 over concerns about antisemitism. At the time, he said Labour had created a “hostile environment” for Jewish people, but he stuck with the party. Now it seems Labour HQ have been working closely with him to try to bounce back from the poor local election results. The government also seems to see him as someone they can work with — the country’s first investment zone has just been announced here. Even though the amount on offer isn’t that significant (£80m), it does suggest the government no longer puts us in the “political basket case” category.

Coppard greets me with a warm but slightly frazzled smile. It’s clear that I’m arriving at the end of a day full of meetings. He’s just been discussing the no-doubt challenging logistics of planting 1.4 million trees, or one for everyone in South Yorkshire.

I kick off with a simple question from one of our readers — what has he delivered in his first year? His answer is decidedly unglamorous: Coppard talks about the internal work he’s undertaken to reshape the combined authority. He points to a full refresh of the top team and changes in how they work — including moving to a “leader and cabinet” model. “We were just too slow at making decisions,” he says, explaining that businesses and universities had been frustrated by repeated delays in management.

Coppard acknowledges that this might seem dry to many, but insists that it’s this sort of thing that will enable him to get a lot more done in future. He also points to his progress on health, and early introduction of the £2 bus fare. He’s taken the decision to bring the tram back under public control, and begun the legal process that may eventually lead to bus franchising.

I’m intrigued by one of his strategic choices. If you’ve kept even half an eye on his Twitter feed, you’ll have seen his new ambition for South Yorkshire to be the healthiest region in the UK. That’s incredibly difficult because health outcomes are famously some of the hardest metrics to move, with health inequalities generally described as “generational”. And it’s not an area where he has any power. Take a look at the devolution deal, and you’ll see health only gets a cursory mention. Why, then, has he nailed his flag to this particular mast?

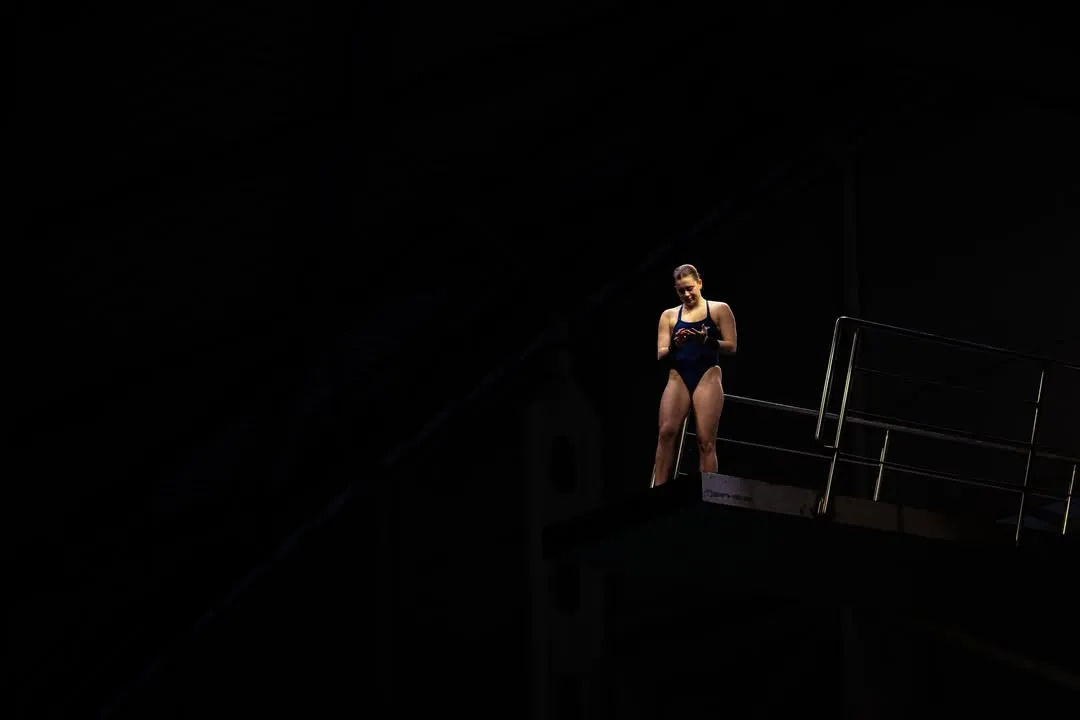

Coppard responds by describing his own experiences of health issues and inequalities. He was first motivated to stand as an MP (against Nick Clegg) after seeing the NHS support his sister through kidney cancer, worrying that the service was being undermined by the coalition government. Then there was a school friend, Idris, who grew up on the other side of Sheffield to him (Coppard went to school in High Storrs) and was a very promising athlete (“aged 16, he posted faster times than Mo Farah”). But being from a refugee family, Idris found it hard to navigate the health system, meaning he didn’t get the support he needed for a curable heart condition. Idris died the month Coppard was elected.

“Do I technically have any responsibility for this, in the devolution deal? No,” he says. But because health is an economic as well as moral issue, he argues it comes under his remit. Coppard points out that about a third of South Yorkshire’s worklessness challenge is around health (something we covered recently). “It’s a systemwide problem,” he says, “and I’m the best person in South Yorkshire to bring those systems together.” To that end, he’s taken on the role of chair of the NHS Integrated Care Partnership, and set up a health equities advisory panel, involving Harvard University and the Bloomberg Philanthropies charity.

Coppard talks fast — not out of nervousness, but a desire to get both his point, and the necessary nuance, across in the time available — even biting his tongue at one stage in eagerness to get the words out.

He’s also a big one for hand gestures — well, full arm gestures, really. When he describes South Yorkshire's future to me, he holds it aloft. He keeps using phrases like “in 5, 10, 15 years…” and “in 10, 20, 30 years…”, delineating these increments with his hands along an invisible timeline. In fact, he diagnoses short-termism as one of the major ills of UK politics, even quoting George Osborne: “We overestimate the impact of politicians in the short term, and underestimate it in the long term.”

We get into the next meaty topic of conversation — transport. Taking the tram back into public hands sounds like a good thing, but given the parlous state of Supertram’s finances (as we have reported) surely it’s a major risk? Coppard doesn’t deny it: “It was a big decision to take, but I think it’s the right one.” He believes the tram can be stabilised by improved marketing and better fare protection. He then wants to see it expanded — though won’t be drawn on where or when. He agrees that the network has been “fairly stagnant” for the last 30 years, and sees that as a symptom of a wider problem. “The privatised public transport system in this country has utterly failed,” Coppard claims, something he also applies to buses.

But there was an opportunity to take more direct control of our buses in the last year — when Powell’s bus company came up for sale. Why didn’t Coppard get his hands on it then — surely a much more direct solution? “If you buy a bus company in distress there are all sorts of issues,” he replies. He claims that Powell’s didn’t give sufficient notice before closing, meaning that when it did shut down many of the assets had already gone, and the buses that were left were in a poor state. He says it wasn’t an ideological decision, and he wouldn’t rule something like that out in future.

Does Coppard support the proposals for “red routes” on Abbeydale and Ecclesall roads? “I’m certainly supportive of bus priority measures,” he responds. He says that though he understands business concerns, putting red lines in is needed if you’re going to use cameras to stop cars parking in the bus lanes. The uncertainty created by taking ages to make these decisions is much worse for business, he believes. “You’ve got to take decisions sooner or later,” he says, which feels like a not very thinly veiled criticism of recent council leadership. In fact, one source describes this as a “mayoral led policy” that was cancelled by former leader Terry Fox. (In the latest twist, the decision over the red lines was “deferred” this week).

Then of course, there’s the vexed question of walking and cycling infrastructure. It was recently announced that South Yorkshire was getting a mere £2.4m from the government for “active travel” — which means walking and cycling — compared to West Yorkshire’s £17m. That’s the kind of thing where you’d expect any self-respecting mayor from the opposition party to be up in arms about. Instead, Coppard agreed that the government wasn’t seeing enough ambition and coherence from our region.

But even small-scale active travel schemes like new barriers on side roads have caused lots of upset, I point out. How can we go big? “What we want is a world in which things like active travel are at the forefront of how people move across our region,” says Coppard. “If we’re going to be a healthier region then part of that is about moving differently across South Yorkshire.” He says he understands why people find the kind of changes needed “scary”, and that it’s on politicians to have those conversations with communities.

Talking about transport naturally leads onto what he describes as the biggest crisis of his time in office — the closure of Doncaster Sheffield Airport. I expect most of us have assumed that we won’t see flights leaving Doncaster again, but Coppard hasn’t given up hope. The combined authority is supporting Doncaster Council to make a “compulsory purchase” of the airport, with the idea of bringing in another operator. Unlike buses and trams, he believes the private sector is best placed to run airports. I put it to him that the decision of the owners, Peel, to shut it down might suggest the airport just can’t wash its face, but he disagrees. “Peel were unable to make a success of it, but that absolutely does not mean anything other than: Peel have made a mess.”

But when net zero is such a priority, why do we need an airport at all? “I wouldn’t belittle those concerns,” Coppard responds, but argues there’s no realistic medium-term future that doesn’t include flying, and that Manchester and Leeds Bradford airports are seriously oversubscribed. “Fewer flights overall: fine,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean we can’t have a thriving airport here in South Yorkshire.”

Crises are a test of leadership – how has Coppard fared? One angle that some critics have taken is that the airport affair is a sign of his naivety. “Oliver waded in… saying ‘I can talk to Peel. I can talk them round,” a source tells me, believing Coppard has too much faith in his ability to charm. They note that early in his career, he spent time out in the United States working on Barack Obama’s presidential campaign, and brought back with him that same confidence in personality politics. In the dirty world of corporate dealmaking, that may not count for very much.

The airport issue also hasn’t endeared him to all wings of his party. One member we spoke to argued that Coppard should simply have gone ahead and bought the airport, as his Tory counterpart in Tees Valley, Ben Houchen, has done. Coppard stresses his “pragmatism” to me, but is there a lack of ideological backbone? Others have highlighted that while he is a keen advocate of bus franchising now, he hasn’t always been so vocal.

This pragmatism may have led to accusations of guilelessness. One rail industry insider refers to Coppard as "Bambi", saying in comparison to other northern leaders he is "ineffective and out of his depth". This source claims Coppard has failed to demand the reinstatement of service connecting Doncaster and Sheffield to Manchester Airport. "He doesn’t understand the difficulties he is going to face," said the source.

Or would a more charitable view be that Coppard simply takes time to work things through and is willing to go where the evidence leads? When I listen back to my tape of our encounter later, I realise that Coppard regularly uses the words and phrases “albeit”, “in my view”, and “that’s fair to say”. If I had to pick a one-word description of his conversational style, I’d probably go for “measured” — he is always keen to communicate not just his point, but all the surrounding caveats that go with it, while acknowledging other perspectives. It’s a trait that might be explained by his route to South Yorkshire’s top job. He previously worked on the officer side of local politics (similar to the civil service in national government). That requires a lot of careful phraseology, relaying messages to politicians they might not want to hear; though I wonder if it becomes a problem when you’re trying to communicate your message to the masses.

I see this evenhandedness again when I bring us round to the possibility of further devolution of powers to South Yorkshire — is the current government even interested in this? “I have to be fair — I think Michael Gove is deeply committed, and doing everything he can to advance devolution.” I hadn’t expected warm words for Gove when I began the interview. When I ask what is top of Coppard’s list for new powers, he points to health, and the ability to retain business rates created in the area. He’s also looking to take on the Police and Crime Commissioner role, which — by a quirk of election timings — would mean he actually has to stand again next year, essentially halving his first term in office.

A Hawaiian shirt appears at the door — we’re out of time. When I ask to take a photo, Coppard offers to put a jacket on, but I reassure him it’s always better to capture things as they really are.

I’m keen to understand more of what he sees as his core mission — health — so we arrange for me to join him for a visit a week later. We meet at the Early Years Community Research Centre, a nursery setting run by a partnership of Sheffield Hallam University, Save the Children, and the local primary school. While this might seem a strange place to go to understand health inequalities, they start from the very beginning of a child’s life and persist.

I’m late — I’d got muddled and thought we were meeting at Shalesmoor, not Shirecliffe, and hadn’t factored in a steep climb up Rutland Road on my bike. The centre’s staff welcome me to the table and graciously give me a large glass of water.

Dr Sally Pearce, director of the centre, talks us through the problem they’re trying to solve. How a child starts in life has a huge bearing on their future health and prosperity. Pearce highlights research on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which include abuse, neglect, family breakdown, parent imprisonment, and multiple house moves. Children who experience four or more ACEs have been shown to be many times more likely to experience poor mental health, be excluded from school, and go on to have alcohol or substance misuse issues in later life. “We’ve got children here who already have four or more ACEs, at the age of two,” Pearce explains.

They’re also seeing a marked effect on child development from the pandemic, with many children arriving with few (or no) words, poor social skills, and poor physical development. And it’s had just as much impact on the parents. “We’ve had parents saying to us that they were actually thinking they might need to give their child up, because they just couldn’t cope,” Pearce says. They’ve created a breakfast club for parents to help with teaching skills for parenting, and provide support with food, health and hygiene.

The site had been a Sure Start centre previously, but was mothballed during austerity. “There was nothing in this community,” Pearce says, and I can feel her anger. Their places are almost entirely given to those children who, due to economic circumstances, are entitled to free childcare. The centre is also being used by the university to research what interventions work well for families. They would like to expand further, but can’t, because of the “recruitment and retention crisis” in the sector. Pearce says these roles “are so undervalued by us as a society”. Low wages, a lack of progression opportunities, and a careers system that penalises schools for sending students down this route all make the problem worse.

Coppard is more vague about what his role will be in solving this — he tells us plans are in motion but that he doesn’t want to “set hares running” (another favourite phrase). He has been tweeting approvingly about Finnish approaches to early years, which famously include the provision of a “baby box” for new parents, so perhaps this is in the pipeline.

Is he confident that the Labour Party gets the importance of this agenda? He tells me Bridget Phillipson, the shadow education secretary, understands, though caveats that if a Labour government does come to power, there will be many demands and little money. “We will inherit a huge mess,” he says. “Across the place, it’s all broken.”

We head outside, to meet some of the children in the centre. I’d expected the presence of two strange, tall, men to make them shy, but quite the opposite — they confidently toddle towards us and try to involve us in their games. They seem really, really happy here. Though he doesn’t have children of his own, Coppard’s a natural, and I’m thankful I don’t have to witness the usual stomach churning awkwardness that comes when you put politicians in educational settings. I, meanwhile, ask the deputy manager more about the centre’s research, while a girl in pink wellies tries to pour water on my shoes.

Afterwards, we catch up for a final time. I’ve found out a lot about Coppard the mayor, but what of Coppard the man? I delve a bit into his backstory — he previously led Yorkshire’s campaign for Britain to remain in the EU. What does he believe the impact of Brexit has been on South Yorkshire? I expect him to equivocate — Brexit being something of a taboo subject among senior Labour politicians — but he’s pretty straightforward that he thinks the impact has been negative, pointing to recruitment challenges, higher inflation and lost funding for deprived regions. He echoes the party line (“we’ve got to make Brexit work”), but not with much relish.

Blades or Owls? “Arsenal!” he laughs, telling me every South Yorkshire club has his equal support. Favourite pub? He does have an answer, but we agree that for security reasons it’s probably best not to reveal his local. As a fellow cyclist, I’m keen to know where his favourite ride is — up to the Barrel Inn, at Eyam. (He got into cycling at 30, after a stag-do where he and friends were too hungover to complete a ride. As an act of penance, they resolved to do a charity cycle to Paris instead, and it went from there).

Later on, I speak to Coppard’s former boss, Annie Crombie. For those looking to paint Coppard as a career politician, there are a couple of points in his CV that don’t really fit the narrative. Firstly, there’s his refusal to stand as MP in 2019 over antisemitism in Labour. And secondly, there’s the job he took for four years before being mayor at the BookTrust, a charity that works with low-income families to get children reading — not what you’d really think of when climbing the greasy pole. At the charity, Coppard was head of English regions, and I’m told that his legacy was getting them to think more strategically about how they work with different places.

What was Coppard like, I ask Crombie. “He’s a real learner,” she begins. “He wanted to learn about how you make things happen, and how you deliver change.” And there was a lot to learn, including setting budgets and managing HR issues — things he hadn’t had to do before. She also believes he’s a good judge of character, who knows who to trust, and who can help. And when he needs help, he’s happy to ask.

And, it seems, Coppard really does care a lot about children’s reading. “He's personally driven to reduce inequalities,” Crombie tells me. Where does that drive come from? I put forward one theory: his faith? Interestingly, for a fairly open character, it’s not something he talks about much. Crombie thinks it’s more the public service background of his family that’s given him that focus. She describes him as a “super social person” who would be the one to put their hand up for organising summer picnics and Christmas parties — an all-round nice guy.

Might that be the key criticism of Coppard: that he’s too nice? After all, in the heavily centralised UK a great deal of local politics comes down to fighting for every penny you can get. The combination of his openness, big focus on social issues, regular use of empathetic personal stories, and a photogenic persona reminds me a bit of New Zealand’s former premier, Jacinda Ardern. Ardern was lauded for her approach to Covid, but left the role not long after, saying: “I am human, politicians are human. We give all that we can for as long as we can.” The South Yorkshire mayoralty is one thing — if Coppard wants to climb to the higher echelons of power, the pressure will only intensify. Can he handle it?

In many ways, it’s too soon to judge. He’s only been in the role for just over a year. The obvious bear traps — taking on the bus and tram — are still to come. And even if he manages to make a meaningful change on his “core mission” of health outcomes, we probably won’t see the fruits of it for decades.

After our interview, I thank Oliver for his time, and we head out of the Early Years Research Centre; Coppard to his car, me to my bike. “I could have given you a lift,” he says.

This article was amended at 12.03pm on 24/07/23 to clarify that BookTrust is a charity that works with low-income families to get children reading.