This story was published by The Tribune, an email newsletter which sends out high quality journalism about Sheffield to 32,000 readers. Our team of independent reporters and editors bring you important investigations, great local writing and useful recommendations about the city. You can join for free by hitting that button below.

Rosie ushers me into her kitchen in Sheffield. She puts the kettle on, and we quickly agree that we’re both too wired to drink caffeinated tea.

She later tells me that she’s been anxious about my looming visit for the last few days. I’m reminding her, and asking probing questions about, the time in her life she most wants to forget.

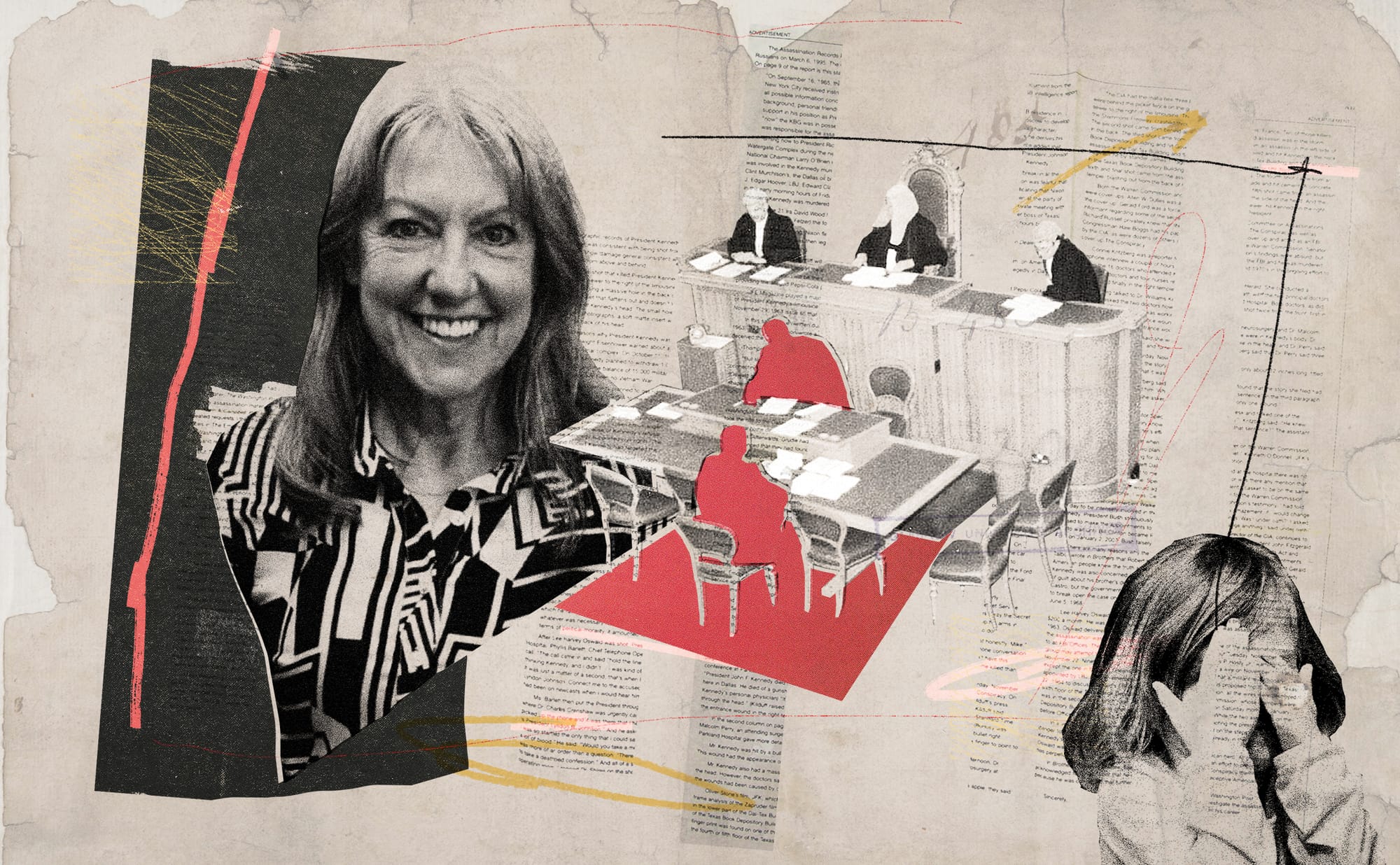

Nevertheless, she sits next to me on her sofa and, while she cradles her ‘mama bear’ mug, explains how her children were almost taken off her. It’s a strange story, that actually begins in 1980s New York, and ends with a Sheffield psychologist using ‘harmful pseudo-science’ to recommend separating children from their mothers.

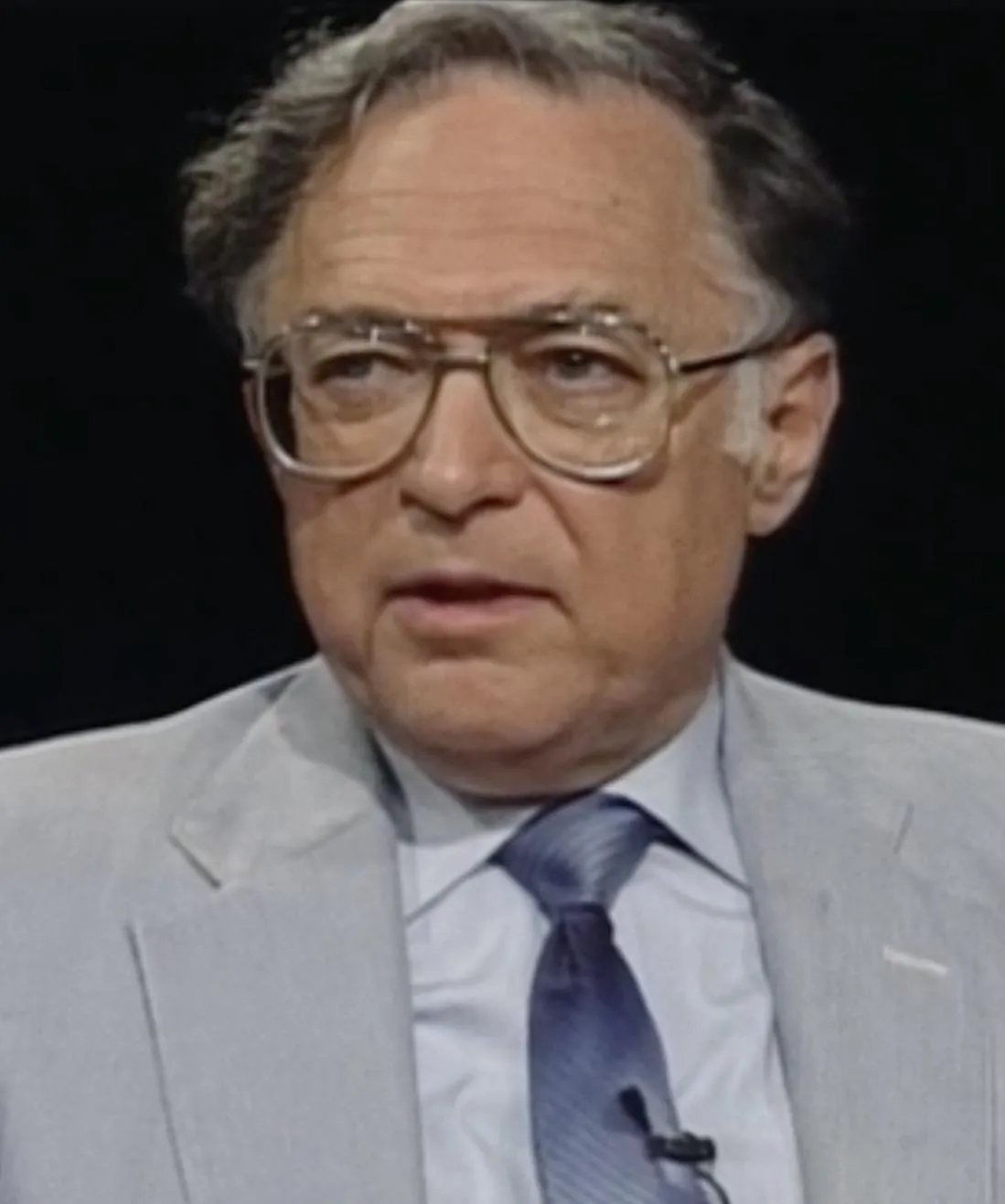

Richard Gardner didn’t shy away from controversy. As a child psychiatrist at Columbia University, he made his name by developing the concept of “Parental Alienation Syndrome” (PAS). In his 1987 book, The Parental Alienation Syndrome and the Differentiation between Fabricated and Genuine Child Sex Abuse, he described PAS as being when “children are preoccupied with deprecation and criticism of a parent — denigration that is unjustified and/or exaggerated.” It comes about by children being “brainwashed” by the other parent (the “programmer”), but also “subconscious and unconscious factors within the programming parent that contribute to the child’s alienation from the other.” Gardner believed he was seeing this syndrome extraordinarily frequently in children going through protracted custody battles — in roughly 90 per cent of cases.

A lot of people didn’t like PAS. Critics noted that when Gardner applied the label, it was almost always the mother who was doing the alienating, and the father who was being alienated. Gardner’s response to that was blunt. “This is the reality. People don’t get angry at doctors who say that breast cancer is more common in women than men. We have to understand the nature of this phenomenon and why it is that women are more likely to be programmers than men.”

Even more concerning were the implications of accepting PAS in cases where children were alleging that they had been abused, including sexually, by their fathers. In his book, Gardner wrote that the presence of PAS “strongly supports the argument that the sex abuse is fabricated.” The fact that a child was saying clearly that they were being abused by their father meant they probably weren’t. It was much more likely, Gardner believed, that they had been “programmed” to do so. “Children who have been genuinely abused do not usually manifest the signs and symptoms of the parental alienation syndrome”, he wrote.

Rosie had a happy childhood. During the week, her dad worked, while her mum stayed home to raise Rosie and her siblings – and then they all went to church together on Sundays. When her grandmother became ill, Rosie helped to care for her, and decided she’d pursue a career in healthcare.

But her keenness to help people backfired in Rosie's first serious relationship. She lent her partner a lot of money and was left in debt and on antidepressants when their relationship broke down.

When Rosie met Liam, she quickly decided to marry him. It was an easy decision to make; Liam was taking her for meals and buying her gifts; he even paid off her student debt. She soon met his family, and they got engaged.

Once they were married, Rosie says she and Liam didn’t see much of each other due to different work patterns, and she didn’t feel like they ever emotionally connected. And then, Rosie says Liam began raping her. She kept quiet – and blamed herself. She’d think of the line in the bible: ‘Deny yourself. Pick up your cross and follow me,’ and decided this was her cross to bear.

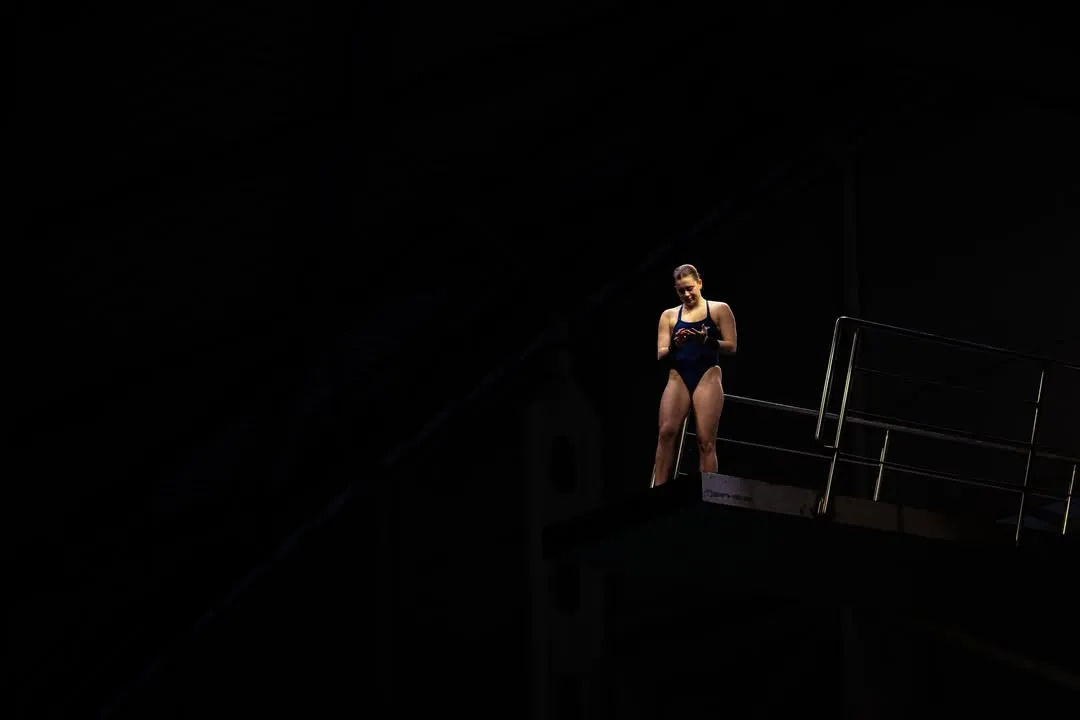

Rosie had two children, but felt unsupported by Liam. She had fleeting moments of wanting to end her life because she felt so trapped.

Then, she met someone else. When she told Liam, he made her end the affair, and she says the abuse worsened. She wanted to leave, but couldn’t afford to. Thankfully, she soon found a a job, and she saved up until she and the children could move out.

At first, they shared custody 50/50, but the children didn’t want to see Liam. Liam started proceedings in the family court. But then, one of the children told Rosie that he’d sexually assaulted them, and Rosie went to the police. Liam was put on police bail and his contact with the children suspended.

The uninitiated might assume this would hinder Liam’s chances of seeing his children. But it's not that simple.

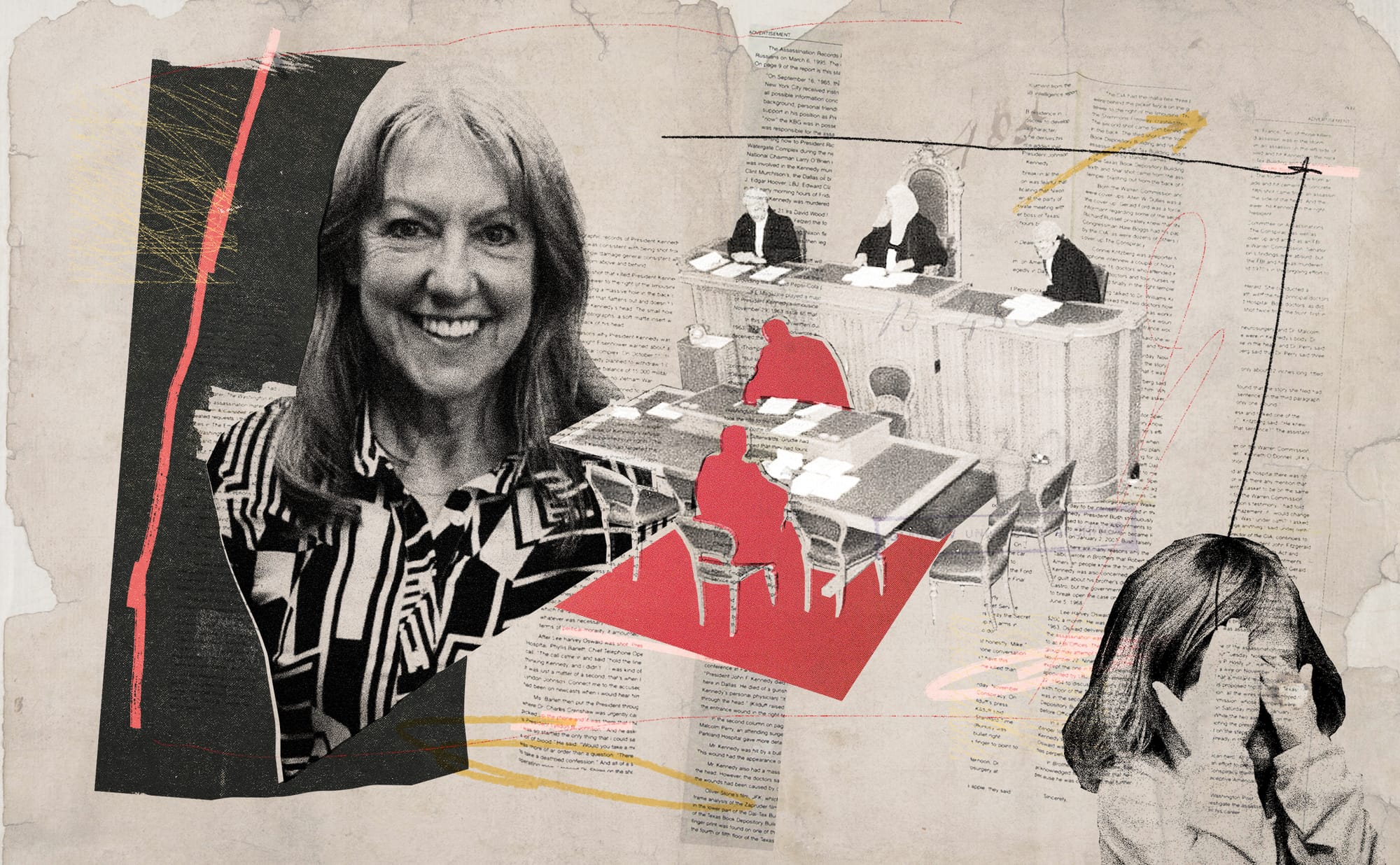

It’s September 2023 and Rosie’s daughter, Lucy, is playing a card game, of sorts, with Dr Maria Downs. She’s been taken out of lessons in her high school. Dr Downs gives Lucy one card at a time, with a description on it, and she has to place it next to a figure that represents a member of her family.

Lucy allocates 32 cards to the figure that represents her father. Of these, 29 are negative. The remaining three are generally interpreted by this psychiatric test as positive traits: the family member who ‘likes to cuddle’, ‘likes to hug’ and ‘likes to be in bed with’ her. But given the allegations Lucy has already made to Dr Downs — the details of which we are unable to publish — they should not be interpreted positively. She allocates 14 positive cards to her mother, and a few to other members of her family.

As well as these psychological tests, she is asked about their family. They detail several allegations of harmful behaviour, including sexual abuse. Lucy also mentions self-harming, which has arisen as a result of the experience.

When Downs writes up her assessment for the court, she reaches a surprising conclusion. “The idealisation of [Lucy’s] mother and devaluation of her father when completing the [test] are suggestive of Lucy using the psychological defence of splitting”, she writes. This is the idea of a person having to “split” part of themselves off — the part that loves the father, in this case — to please the other parent.

As for the allegations of abuse, it is worth quoting Downs’ assessment in full:

“[W]hile rejection of an abusive parent is considered to be an adaptive coping strategy where the child has been subject to abuse, such a response is highly unusual. Children have an innate, evolutionary drive to attach to their caregivers irrespective of the quality of care received, even where the caregiver is abusive. Most children who are abused by a parent struggle to disclose their abuse due to feelings of confusion and issues of loyalty and inner conflict. They usually resort to internalising coping mechanisms such as denial, silence and secrecy.”

She concludes:

“False allegations of abuse, misinterpretation or exaggeration of non-abusive incidents are commonplace where there is dispute over child arrangements, and parental alienation in particular.”

Downs was writing three and a half decades on from when Gardner published his book. But the ideas are identical. If the child was being abused, they would struggle to disclose it. The fact they are disclosing it means it’s probably not happening. It’s probably parental alienation instead.

(There are, of course, cases where allegations of abuse are fabricated. But to describe this as “commonplace” is incorrect. One analysis of multiple studies found that estimates typically range between 2% and 5% of cases. What is absolutely clear is that allegations of abuse should not be used as evidence against abuse.)

And so, Downs concluded, the children were insecurely attached to Rosie and suppressing their own needs to prioritise hers. There was a risk of the children developing psychiatric and personality disorders if Rosie didn’t ‘change her stance’. And she suggested that, if Rosie wouldn’t engage in mediation therapy with Liam, the judge should consider giving Liam custody, and suspending Rosie’s contact initially, before giving her supervised contact until she could demonstrate her capability of promoting a healthy relationship between the children and Liam.

Rosie was stunned. There, in black and white, Downs had written: “[The child]...can recall incidents in which she was abused physically and possibly sexually.” And yet, Rosie was the problem.

Richard Gardner died by suicide in 2003. At that time, the concept of parental alienation had only just begun being used in UK family courts, and generally without success. But ideas often outlive their parents, and the use of parental alienation arguments in UK family courts has been growing. As well as Rosie, I spoke to five other mothers who had all been in cases involving Maria Downs. In each case, “parental alienation” was used to argue for fathers having access to their children in cases where abuse was being alleged.

People like Anna, whose child was ordered by the court to move in with the dad, despite his being arrested for domestic abuse. Downs was instructed to assess the family, and concluded that Anna was causing her daughter’s ‘splitting’ behaviour and that the dad posed no risk. Downs repeatedly suggested suspending contact between Anna and her daughter, and said the daughter didn’t show signs of having been significantly affected by witnessing abuse perpetrated by the dad towards Anna (despite only meeting with her for two hours). The judge’s decision was eventually overturned by another judge, who concluded that the dad had a ‘striking’ lack of empathy, and the daughter returned to Anna.

Or Nicola, who is still battling the courts to prevent her son from being forced to see the father she says abused him. “It’s so out of hand, I just don’t understand it,” Nicola told me. “It’s all down to Downs. It’s as if the court can just decide that a happy, safe child needs to be taken away from home.” And then there’s Veronica, who has been cast as an alienator despite the dad being deemed dangerous by professionals, and Becky, who endured a long court battle that has drained her savings after simply raising a safeguarding issue regarding the dad.

A study by Elizabeth Dalgarno, director and founder of SHERA Research Group, interviewed 45 mothers who were domestic abuse victims. All went through private family court proceedings, and 39 of them were accused of PA. The remaining six were threatened that they’d be accused of it if they didn’t agree to contact with the dads. The research found that “investigation of DA [domestic abuse] in these cases was diminished or ignored due to the PA allegations”. “We found that whatever mothers raised, it was construed as alienation,” Dalgarno says.

The success of the parental alienation argument has led to it being used more and more frequently. As Adrienne Barnett, teacher in Law at Brunel University, has found: “more recently, a PA ‘industry’ appears to have amassed, comprising experts, therapists and lawyers.” There’s certainly money to be made — expert witnesses can charge up to £100 per hour, and up to £500 an hour for appearing in court.

After reading Downs’ report, Rosie was terrified that the judge would take her advice. “My kids are my world. If I didn’t have them any more, then what am I? How do you carry on with your life?”

But the unambiguous recommendation of a psychological expert carries a lot of weight. The judge did take up Downs’ recommendation: Rosie had to agree to joint therapy with Liam, or risk losing the children. “I felt backed into a corner again. I said, ‘this isn’t parental alienation – we’ve been abused’,” she says. “I was pleading with them to understand – I kept thinking, am I crazy? Why is no one seeing this?”

Dalgarno tells me the toll court proceedings take on women is often used to bolster the accusations of PA. “The system is so abusive, not just directly, but it exhausts the mothers,” she says. “They’re still working and mothering, and very often are [representing themselves], which is a full-time job in itself. They’re desperate to protect their children. The father says, ‘Look, she’s a mess, she can’t look after the children, she’s a crazy alienator’.”

The world of family courts is murky. It was only this year that journalists were first allowed to report on them (we would not have been able to publish this story last year). And so the growth of the parental alienation ‘industry’ has gone mostly unnoticed.

But at the end of last year, the Family Justice Council (FJC), an official body set up to advise the courts, decided enough was enough, and published guidance about its use. “A child’s reluctance, resistance or refusal to spend time with a parent is often alleged to be a result of ‘parental alienation’. Despite the lack of research evidence, and international condemnation, reference is still made to the discredited concept of ‘parental alienation syndrome’”, they wrote. “For the avoidance of doubt, the Family Justice Council (FJC) recognises that ‘parental alienation syndrome’ has no evidential basis and is considered a harmful pseudo-science.”

This story was published by The Tribune, an email newsletter which sends out high quality journalism about Sheffield to 32,000 readers. Our team of independent reporters and editors bring you important investigations, great local writing and useful recommendations about the city. You can join for free by hitting that button below.

They also added that “[i]n light of their respective prevalence, and the relative harm to children and adult survivors, allegations of domestic abuse and ‘parental alienation’ cannot be equated.” In cases where abuse had been found, ‘alienating behaviours’ would no longer be an acceptable argument, and courts were told it was “inappropriate” to use experts to determine whether alienation was happening. The boom days of the parental alienation industry may be coming to an end.

We asked Maria Downs why she had been using arguments described by the FJC as “harmful pseudo-science”. And we asked if she regretted that in cases where she had used these arguments, children had been separated from their mothers, and placed with fathers that they alleged were abusing them. We were told, via a spokesperson, that Downs was not going to comment due to the confidentiality of the cases.

We replied that we thought these questions could still be answered without reference to specific cases. We also asked Downs why her website had previously included “parental alienation” as a service provided, but this had now been taken down. We heard nothing more.

For Rosie and her daughters the story ends, for the most part, happily. She appointed another barrister, Charlotte Proudman, to take on the case. When Proudman reviewed Rosie’s files, she asked her: “do you realise how close you are to these children being taken off you?” Proudman suggested getting Rosie’s daughter her own representation, and, with a new judge at the helm, the case turned around.

Proudman has worked on many cases where ‘alienation’ has been argued. She told The Tribune: “We see experts such as Dr Downs and other ‘alienation’ specialists changing the language from ‘parental alienation’ to other terminology such as ‘splitting’ but it means the same. Many experts have carved out a niche practice of alienation in family courts meaning they become the go-to expert on behalf of fathers and legal teams who want a ‘diagnosis’ of alienation and often removal of children from their mother (who is often a victim of abuse) to their father (who can be a perpetrator of abuse). I have seen in these cases children’s allegations of abuse being ignored, or even findings of abuse minimised because of alienation.”

But years of arguing in the family courts takes a toll. Rosie didn’t qualify for legal aid, so she’s in a lot of debt. And she is haunted by Downs’ ghost. She remembers what car Downs drives, and every time she sees the same model and colour on the road, she prays it isn’t her.

The year before his death, Richard Gardner gave a lecture in Frankfurt to defend his much-maligned thesis. He opened with the words of the philosopher Schopenhauer: “All truth passes through three stages: First, it is ridiculed. Secondly, it is violently opposed. Thirdly, it is accepted as self-evident.”

Yet parental alienation has only ever been self-evident to a few. The last man to cross-examine Gardner in court, attorney Richard Ducote, commented upon his death that: “Parental Alienation Syndrome is a bogus, pro-pedophilic fraud”. He also noted that Gardner hadn’t had hospital admitting privileges for over 25 years, and had stopped being asked by courts to witness. “Let’s pray that his ridiculous, dangerous PAS foolishness died with him,” Ducote added.

His prayers went unanswered. Though in America Gardner’s ideas had been widely discredited, in Sheffield they live on, two decades later. In cases like Rosie’s, the drawn-out court proceedings have caused huge harm. In others, like Nicola’s, it’s ongoing. Rosie is worried that Downs is still practicing and potentially being instructed to write more psychological reports in the family courts. “It’s terrifying, and I just can’t see how it’s going to stop,” she says.

All names of family members have been changed.

This article was updated at 17.40 on the 9th August. We previously suggested Downs was incorrect to claim to be an honorary teacher at the University of Sheffield, after the university told us this was the case. We have now been informed otherwise, and have removed this from the piece.

This story was published by The Tribune, an email newsletter which sends out high quality journalism about Sheffield to 32,000 readers. Our team of independent reporters and editors bring you important investigations, great local writing and useful recommendations about the city. You can join for free by hitting that button below.