When we were first told about it, it seemed implausible. Workers at the University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC) had been overheard joking about “making WMD” — weapons of mass destruction. Specifically, nuclear weapons.

The UK’s nuclear weapons programme is shrouded in secrecy. It’s overseen by the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE), which is a branch of the Ministry of Defence, and one of the most impenetrable parts of the British state.

AWE is based out of an ultra-secure site in Aldermaston, Berkshire. Across 750 acres, thousands of staff work on the nuclear defence programme at one of the most covert defence sites in the UK. Above ground, the buildings are surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards patrol the rooftops; below it are vaults containing components made from weapons grade uranium and plutonium.

These components are assembled into warheads at a nearby site, before being driven all the way to Scotland for mounting on Trident nuclear submarines. Every time a new prime minister walks through the door of 10 Downing Street, one of the first acts required of them is to write “letters of last resort”, telling the submarine commanders what their orders are in the event of a devastating attack that wipes out the country’s leadership.

The current warhead design, Holbrook, entered service in the 1990s, but stocks were gradually wound down through the 90s and 00s. However, amidst a backdrop of growing international tensions, at some stage the decision was taken that the UK needed a new design of warhead, which was announced in parliament in 2020. This was to take its name from the Greek goddess of justice, innocence, purity, and precision: Astraea.

If staff at the university were working on Astraea we knew it would be very hard to prove. But it couldn’t hurt to run the tip past a couple of people in the know. After all, the AMRC — the beating heart of South Yorkshire’s manufacturing industry — does indeed work with large defence companies like BAE and Rolls Royce. And who really knows what goes on behind those anonymous glassy frontages next to the Sheffield Parkway?

These early conversations, however, only seemed to confirm that the tip was a non-starter: one person said they were sure the AMRC’s systems weren’t secure enough for such high-level defence work; another commented that AMRC just didn’t have the supply chain to be involved in this sort of thing.

And that might well have been that, had it not been for two things.

Firstly, our original contact is well connected in the manufacturing world, and thought there was more to the story. They had been reliable in the past, so I struggled to discount them.

Also, I’d begun reading more widely about nuclear weapons and was starting to get interested. If the programme to develop Astraea had begun a few years ago, that would put them in the early design phases, exactly the point where it might help to have a partner with expertise in highly advanced manufacturing processes. Was it just possible that AMRC were involved in this work?

And there was a third reason I wasn’t willing to put it down straight away. Last year, in an interview with the Times Higher Education supplement, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Sheffield, Koen Lamberts, was asked what the AMRC would, or would not, do with a defence contractor.

Lamberts was unequivocal. It was “utterly unthinkable” that AMRC would manufacture weapons components, he said.

So, if there was even the slightest possibility that AMRC were actually involved — not just with weapons, but the most destructive weapons mankind has ever created — we wanted to get to the bottom of it. After all, this city has history with nuclear weapons, famously declaring itself nuclear free in the 1980s. The portrayal of Sheffield devastated by a bomb in the 1984 film Threads still haunts many nightmares.

‘A deliberate tactic of delaying’

I started in the most straightforward way I could — by asking direct questions. It was only later that I had to get more creative.

My first freedom of information (FoI) request was to AWE. I asked who their major contractors and partners were in the Astraea programme.

At the same time, my colleague Dan Hayes put in an FoI to the university. For this, we asked about a LinkedIn post from Steve Foxley, who until last year was Chief Executive at the AMRC. He had mentioned that over the last five years, the AMRC had netted its biggest ever commercial research contract. Our question was simple: what was it?

Both organisations took different approaches to not answering the questions we gave them.

AWE missed the statutory deadline of 20 working days, and then asked for an extension while they carried out “public interest tests” to establish whether they should divulge this information. They then stopped replying to my e-mails. While the law allows for an extension of a further 20 working days, over 60 working days on from the original request they still hadn’t got back to us.

The university said they wouldn’t answer our question because it was “information provided in confidence”. It seemed a strange argument to make. After all, we weren’t asking for any sensitive details of what their biggest contract involved, simply who it was with and a broad outline of the work. Given the tens of millions of taxpayer money that has gone into AMRC, we appealed on the grounds of public interest, but were then met, again, with silence. The unwillingness from both to give us a straight answer made me wonder if there was more to this after all.

It was around this point that I first started speaking to David Cullen. Cullen is the former head of the Nuclear Information Service (a research organisation that favours disarmament), and a policy expert at think tank BASIC who has written widely on the UK’s nuclear weapons programme. He told me that “delinquent compliance with Freedom of Information Requests is sadly common within the Nuclear Weapons Programme... It appears to be a deliberate tactic of delaying in the hope that requesters will become worn down and give up.” Clearly, I was going to have to find another way.

Cullen put me in touch with another colleague at NIS who had written a report about defence activities at the University of Sheffield. He in turn pointed me to a report put out last year by Sheffield Campus for Palestine, a student group. That report made a quite startling claim:

“The Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE)… is leading the new programme to replace the current stock of warheads. This includes basing a Project Engineer working on nuclear warheads directly at the AMRC.”

Having almost given up on this story at the beginning, this made me sit back in shock. It was the first document I’d seen to draw a line between AMRC and the MoD’s nuclear weapons body.

Sorry to interrupt! But you can get much more of our vital journalism about Sheffield by joining our mailing list. Just click below, no card details required.

But was it simply the product of overactive student imaginations? The report only gave one source: a job advertisement from AWE. I clicked the link, but it had already been taken down. I contacted the students, but none of them had thought to take a screenshot or otherwise make a record of the advert.

Even without the job ad, the URL of the link was intriguing. It included the words “project-engineer-awe-jv”. JV is common business shorthand for “joint venture” – a formal business partnership between two organisations. If there was a joint venture between AWE and AMRC, it would suggest that AMRC was no mere contractor on the project, but a major partner.

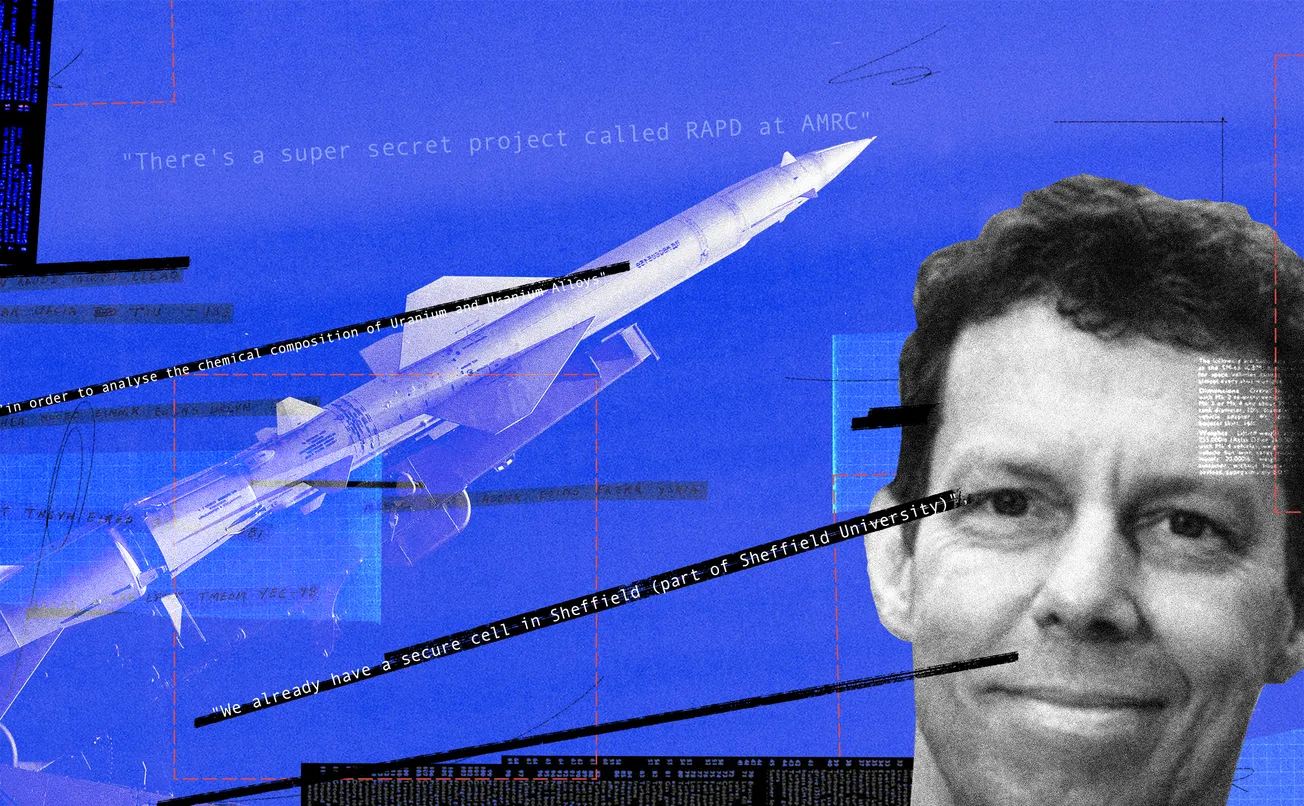

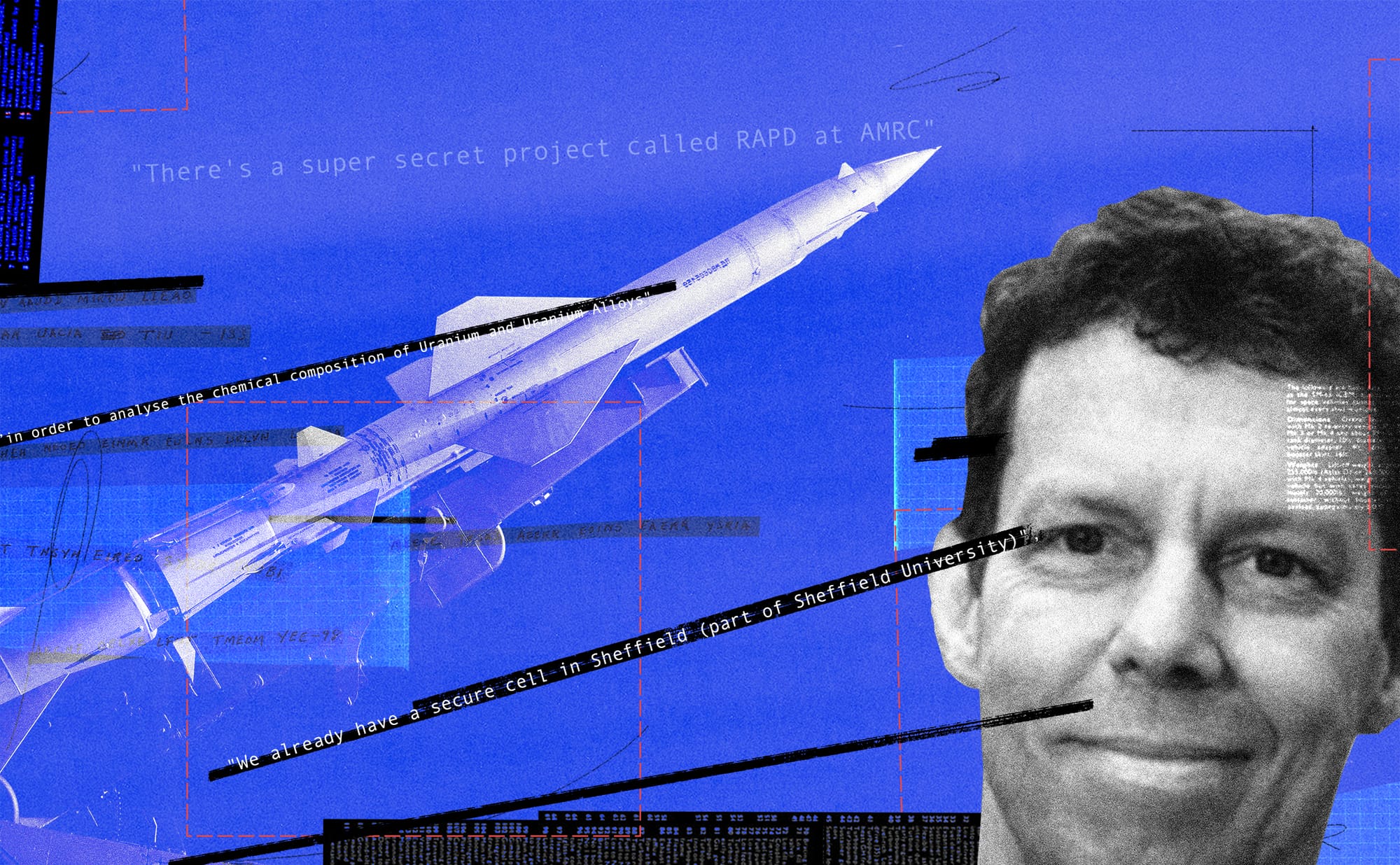

‘There’s a super secret project called RAPD’

Every attempt to retrieve the job ad was drawing a blank. But in the meanwhile, another development had taken place. One of the people I’d spoken to had a friend within the AMRC. They didn’t know what exactly was going on, but they knew there was something. After a conversation with them, my contact passed back this summary via a secure message:

“What they’ve told me is there’s a super secret project called RAPD at the AMRC, it has its own separate secure network and any info about it needs security clearances etc. No one seems to know what RAPD stands for.”

Despite over a month of trying, we still haven’t been able to find out what RAPD stands for. Neither the university or the Ministry of Defence were willing to tell me. But, in a way, that doesn’t matter. What’s more important is how it’s been used.

There are passing references to RAPD in university council minutes. In October 2023, the university council delegated authority to the director of finance to increase the project’s budget in line with the demands of the customer, provided this was “wholly externally funded”.

More revealing has been the way that RAPD has cropped up in procurements by the university. When a public body wants to buy something over a certain value it has to publish a notice on the government’s Contract Finder portal. A search revealed that the university had used that exact code — RAPD — in 16 of their procurements between 2022 and 2023.

These procurements all follow an identical pattern. Each states that they are being carried out under the Defence and Security Public Contracts Regulations 2011, and that bidders must sign non-disclosure agreements. The full details aren’t released, but they do say what they’re looking for.

Many items on the list seem obscure to someone from outside the manufacturing world. “Expanding mandrels”, a “mould turning device”, a “horizontal lathe”.

But a couple of the notices were much more eye-catching. Equipment “to analyse the chemical composition of Uranium and Uranium Alloys”. “Radiation Detection Equipment”. There was also a vague requirement for a “specialist system”, with the contract being awarded to Berthold, a company who specialise in radiation protection.

I sent the full list over to David Cullen, who told me he could see a clear picture. Components, made out of metal, were being cast in graphite moulds, and shaped on a lathe. Given the requirement to test objects made from uranium, it seemed most likely that the uranium was the metal in question.

Cullen also noted that there were two procurements specifically relating to the use of argon — an “argon glovebox for the ability to process materials in a controlled argon atmosphere”, and “a containment solution for a Grob G550T machine tool to allow for machining to occur within an argon atmosphere”. Argon is an inert gas which can prevent oxidation when working with metals like uranium. So wherever the work was going on would need to have a supply of argon on hand.

The job advert

6th June, 2025. The Tribune’s intern, Faye Bramley, is walking around the AMRC’s Design Centre. She’s looking for something specific. No-one challenges her or asks her why she is looking around and even taking photos.

The Design Centre is an unusual curved building that fronts onto a roundabout. An astute observer might have noticed some subtle changes to the building recently. Planning documents lodged last year included an application to build an extra electricity substation, extra security for the windows, a new gas storage tank and an evacuation shelter.

I’d asked Faye to see whether the changes set out in the documents had happened on the ground. Sure enough, it was all there. And on the side of the large gas tank were printed three words: Liquid Pure Argon.

At this point, Cullen suggested there were two leading possibilities.

One was that the AMRC were working on the UK’s nuclear submarines. The university has an established partnership with Rolls Royce, who make the uranium fuel cells that power them. Perhaps the AMRC were collaborating with its partner in working with this material?

But two things didn’t fit. The first: if the AMRC were working on fuel cells, they would be working with extremely highly enriched uranium to deliver maximum propulsion. That comes with a big regulatory footprint. But I’d spoken to the Office for Nuclear Regulation, who confirmed to us that they weren’t regulating the AMRC and had had no discussions to that end.

And there was an even bigger problem: if it was just about powering submarines, would AWE be involved?

Of course, by this stage I still hadn’t managed to prove AWE really were involved, as the students had claimed. But then I had a breakthrough on the job advert.

After almost giving up, I’d remembered something from my previous job, which involved doing economic analysis for local authorities. There were, at the time, some start-up companies who were getting into “scraping” job ad data. They would harvest it from the internet and use it to tell local authorities which jobs were being advertised in their economies, and therefore where their economic strengths and weaknesses lay.

I managed to find one online product with a free trial, and looked up all job adverts from AWE. And there it was.

“We have an exciting opportunity for a Project Engineer to facilitate the growth and engagement at AMRC (Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre)”, it reads. The role was based in Rotherham (the AMRC is situated just over the council border) and included “developing manufacturing processes”, “concept development and testing” and “advanced component manufacturing”.

This was not only confirmation that AWE and AMRC were working together, but also suggested a deeper relationship, which included AWE placing staff full time in AMRC’s building. We were later told by an AMRC insider that AMRC “gave the AWE a bollocking over the job ad… because they didn’t want to be publicly associated together.” It suggested a certain amateurishness in how AWE and AMRC were working on the programme — and any hostile power monitoring AWE’s public notices would immediately have been alerted to the connection.

All the facts fitted one explanation: the AMRC was working with the Atomic Weapons Establishment on the development of the UK’s new nuclear warhead.

“We already have a secure cell in Sheffield”

1st July, 2025. I’m now convinced. But just because everything lines up, it’s not enough to publish. I need proof.

My working assumption is that I’m most likely to get it from someone inside the AMRC. Some staff may have qualms, or a document may have slipped through the net and into the public domain. I’m certainly not expecting confirmation to come from the ultra-secure world of AWE.

But I’m wrong.

Unsurprisingly, AWE publishes very little. But they do have occasional meetings with local parish councillors around their Berkshire site, hailing from places with names like Stratfield Mortimer and Tidmarsh with Sulham. It’s a forum to talk about AWE’s activities, and how they might impact the surrounding region. And in the published minutes, I finally find what I’d been searching for.

It was the 108th meeting of the committee, in November 2023. Andrew McNaughton, the Executive Director for Infrastructure on the Fissile Programme, addressed the room. “The facilities that we have for manufacturing products need to be updated so we can achieve our programmes of work”, McNaughton explained. AWE has not had to design new warheads for decades, and taking this on will require new buildings and facilities, he said.

But in the meantime, they were doing some work elsewhere. And this was where the key admission was made.

“We already have a secure cell in Sheffield (part of Sheffield University) where we have some of the equipment we have been using… where we are going to be trialling the processes and training some of our employees,” McNaughton said.

This proved what we’d been told at the start: in developing the Astraea programme, AWE is working with the University of Sheffield.

David Cullen, the nuclear weapons expert, told us: “The evidence gathered by The Tribune clearly shows that AMRC is working on uranium components in collaboration with AWE. I have no doubt that the University of Sheffield is a partner in the early stages of the Astraea programme.”

We asked AWE for details about the nature of the “secure cell”, and the processes being developed at Sheffield. They didn’t answer our questions. But for the first time, they confirmed they have a relationship with AMRC, saying: “AWE has been a tier-1 member of the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre, a world-leading cluster for research, innovation, and training, since June 2015. It would not be appropriate to provide details of AWE’s relationship with academia and industry for national security reasons.” Presumably this is why AWE has still not responded to our FoI request.

Neither AWE nor the AMRC took the opportunity to dispute our story, or suggest we would be either misleading the public or endangering national security by publishing it.

“Utterly unthinkable”

Not much is known about the specification for Astraea. The current Holbrook warheads have a yield of between 80 and 100 kilotonnes of TNT equivalent. According to the Guardian, experts expect Astraea to be more powerful than this, and possibly closer to 475 kilotonnes. That would be over 30 times as powerful as the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, which is believed to have killed more than 100,000 people.

The warheads themselves will be manufactured in Aldermaston. In their response to our reporting, the university stressed that their work “does not involve production of components for deployment.”

But clearly, the University of Sheffield’s AMRC is making a very significant contribution at this early stage of Astraea’s development. I already knew it was significant enough that AWE had set up a ‘secure cell’ here, and was placing staff directly at the AMRC. Just how significant only became clear last week, when the university finally responded to our original FoI about the largest commercial research contract the AMRC has ever had. They would neither confirm nor deny who the client was, on the grounds of national security. It therefore seems highly likely that working on the warhead programme is the biggest moneymaker in AMRC’s history.

A spokesperson for the university told us: “Our work at the AMRC involves developing and testing new technologies and processes for manufacturing companies and does not involve production of components for deployment. Our collaboration with partners in the defence sector helps them to overcome sustainability and productivity challenges, and support UK security and sovereign capabilities.”

I’ve been working on this story for four months. I have no previous experience with the defence sector, and I assumed it would be an interesting diversion that would ultimately lead nowhere. Instead, largely by relying on freely available documents, I’ve been able to reveal where a significant aspect of the UK’s nuclear weapons programme is taking place — in a building with apparently minimal security just outside Sheffield. It’s possible that others with more of a headstart — and with less benign motives — have been able to do the same.

If the plan was to hide the ‘secure cell’ in Sheffield, then there have been failures on all sides; from the workers at AMRC overheard joking about the programme, to AWE’s decision to publish a job advert online linking them to Sheffield and discuss the ongoing work in a publicly minuted meeting. The mayor’s combined authority has also dropped hints: a document shared at an event in 10 Downing Street with other local leaders said that “creating a secure Defence Facility at the University of Sheffield, in partnership with defence primes (e.g. AWE)” was one of the top priorities locally.

But, given the lack of pushback (we haven’t been asked not to publish) perhaps the parties involved aren’t too concerned. One person close to Mayor Oliver Coppard told us there was previously some “squeamishness” about getting involved in the nuclear sector, due to Sheffield’s history, but in the end the opportunities were too good to pass up.

Some readers will view the university’s contribution to warhead development as a positive reflection on Sheffield’s economic strengths. Others will see a worrying abandonment of the city’s core principles. And still others will question why manufacturing weapons components was described as “utterly unthinkable” by VC Lamberts, even as the AMRC was working on a next-generation warhead.

At least three years on from the start of the university’s involvement, that discussion can now take place.

Additional reporting by Dan Hayes and Faye Bramley

Do you know more about this story? Send us an e-mail, or you can contact us via the secure Signal messaging app at thetribune.11

We’ve made this piece free to read as we think this story is strongly in the public interest. But in terms of the time put in, it’s been our most costly ever to produce. Investigations like this one involve lots of dead ends and fruitless enquiries before you can get to the truth.

If you think this work matters, then we are unashamedly asking for your support. Less than 10% of readers currently back us with what allows us to do these investigations — cash. Please join our committed community of members today, and help us do more of this journalism.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.