Last week, while idly scrolling through social media, a picture in my feed made me stop. It was a photo of Kathleen Roberts — Sheffield’s Last Woman of Steel — in her gown and mortar board as she was awarded an honorary doctorate in engineering from the University of Sheffield. The accompanying story told me she had just died, aged 103.

When I heard the news, I dusted off the audio recording of a memorable chat I had with her for Crone Club in 2022. I set the club up to surround myself with kick-ass older women, learn from their wisdom and remove some of the fear being fed to us on social media about getting older. We wanted to reclaim the original meaning of the word crone, which is derived from cronus, meaning time. Far from being an insult, the word once represented the timeless wisdom older women have.

Three years ago, it was for this reason that I had Sheffield’s last remaining Woman of Steel in my sights. This time, the knowledge of her passing still fresh in my mind, I wanted to pull out what lessons we could all learn about life and growing older from this wonderful woman — one of the last of a generation to whom we owe so much.

Lesson 1. Use your voice wisely…and laugh

“I should think the people of Sheffield have had enough listening about me,” says Kathleen, as she settles into her sofa on a boiling hot day in August 2022. Thankfully, she’s still happy to talk to me. Having just entered her 101st year when we meet, “The Last Woman of Steel” has become a (Sheffield) National Treasure, a moniker that she shrugs off with typical South Yorkshire humility.

Sheffield’s Women of Steel are now well known, as visitors and locals alike pose for selfies by the statue in Barker’s Pool unveiled in 2016 to celebrate the women who worked in the city’s steelworks during both wars. Four of them were involved in the campaign. As well as Kathleen, there was Kitty Sollitt, Ruby Gascoigne and Dorothy Slingsby, all of whom were in their 80s when the Women of Steel effort began.

“Kit, she worked on her combustion thing, where sparks used to fly,” Kathleen tells me. “She'd hardly any hair because it had all got burnt off. Then there was Ruby, she worked on the bridge for D-Day, what did they call it, the Mulberry Bridge. Dorothy was a crane driver and I worked in a rolling mill at Brown Bayleys. I believe it’s a sports field now.”

It took the four of them seven years of hard work to finally get the recognition they deserved, but it was also great fun. “We just had a lovely journey and lots and lots of laughs,” she says. “Ruby, she was a natural comedian, always laughing.”

Lesson 2. Make peace with death and impermanence

I’m speaking to Kathleen at her retirement home in White Willows in Jordanthorpe. Her flat is bright and airy, but her fridge freezer has just packed in. This leads us on to a discussion about the practical dilemma of buying white goods when you’re 100, and most likely won’t see out the three-year warranty. She’s just decided against replacing her sofa for the same reason. “Whoever comes in after me, they might not like it,” she muses, cheerfully.

It’s refreshing to meet someone who has so clearly made their peace with the transient nature of life and the reality of their own death, without any sign of regret or sadness. But Kathleen, like so many women of her generation, doesn’t need the Death Cafes favoured by my cosseted generation. These are the women who were born in the aftermath of the First World War, and were teenagers, and then young women, throughout the Second. It was a time when death was very much part of life. She gets out some pictures to show me. One is of her beloved husband, Joe, having a shave on top of a trench, the evening before the second battle of El Alamein. It’s so quietly poignant, it gives me a shiver.

But while Joe would talk about his time in the desert, he would never speak about D-Day, where he was seriously wounded. “No way would he talk about that,” she says. “He was so...he used to cry a lot after D-Day. And I mean, I thought that was awful because he'd seen lots of battles while he was in the Eighth Army. And it took just that one day…”

As well as lots of hard-hitting investigative journalism, The Tribune also loves publishing human stories about great Sheffielders like Kathleen Roberts, the city's last Woman of Steel.

If you're enjoying our work and believe in the importance of local journalism, you can currently join The Tribune for £4.95 a month for the first three months. We'd love to have you on board.

Lesson 3. Speak your mind (but don’t moan!)

Steering the conversation back to her time in the steelworks, I clock a book by Jojo Moyes on her bookshelf that I recognise. “Oh, The Giver of Stars!”, I say excitedly, before coming up with what I feel is the perfect segue: “Did you see any parallels between the sisterhood battling the patriarchy in that book, and your time in the steelworks?” Kathleen thinks for a moment. “No, not really,” she says and we both laugh.

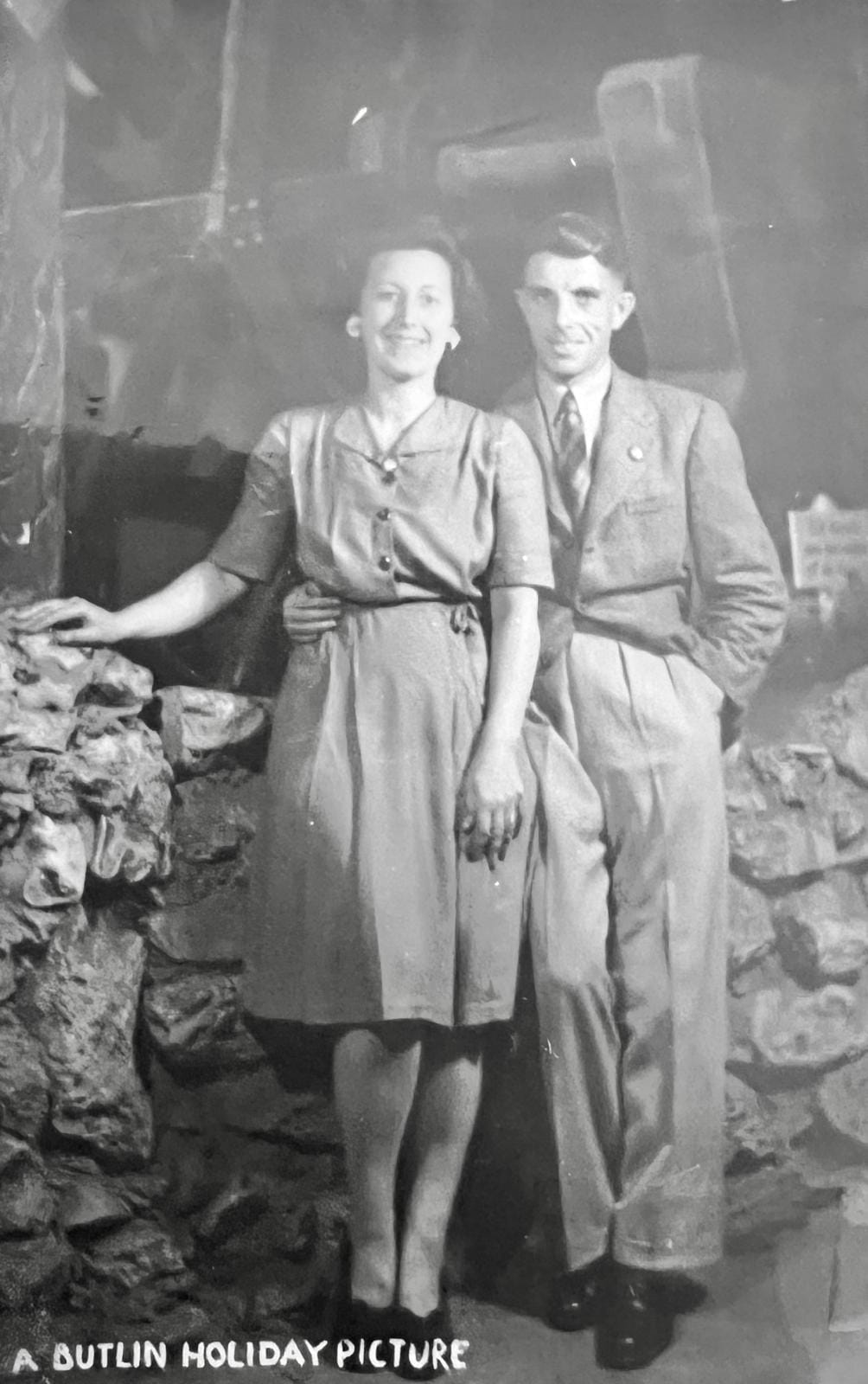

Later, when I read Michelle Rawlin's wonderful book Women of Steel, I realise that straight-talking has always been in Kathleen’s arsenal. “Don't ever wear that suit again — it doesn't suit you at all,” she told Joe when they met at Coles Corner on their first date, not long before war broke out.

But there’s a time to speak, and a time to not speak, and moaning is something Kathleen has no time for. The passage of time and the way the world changes are just facts of life that you have to get used to as you age, she tells me. “That’s life, it's always changed. It's never the same,” she explains. “Don't moan about your aches and pains. Just get on with life.”

Lesson 4. Acts of service and sisterhood

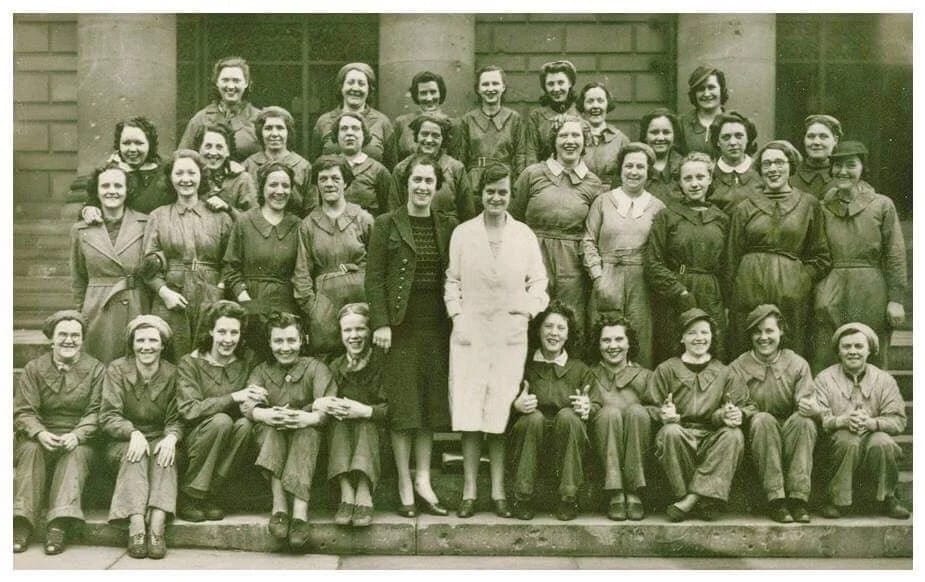

Kathleen’s first steelworks was at Metro Vickers at Tinsley, where she tells me she was building ‘stators’ — round, stationary coils to be used in Spitfires. Metro Vickers also had a hockey team, where Kathleen played right half. Her eyes sparkle as she speaks proudly of the team’s achievements. “We were always in the Green ‘Un,” she adds, proudly.

Learning the job was their first challenge. “When I first went to Brown Bayleys, the men wouldn't show the women anything,” she says. However, after a lot of mistakes and a lot of accidents, they got good at it. “Sometimes you were better than the men — because our fingers were more nimble,” she says. “So we thought, right, we can manage without you.”

I ask her about the Sheffield Blitz — was it scary? “I was at work on nights,” she explains. “We knew they were over the coast because all the lights in the factory went blue, dark blue. But we had to carry on working. We couldn't stop the machines.” Fortunately, Kathleen’s factory was never bombed. “We were very lucky,” she says. “We used to hear them going over night after night…you could look up at the sky…hundreds of black planes going over.” Nevertheless, work continued. “We got used to it…we didn't bother going in the shelter.”

Lesson 5. Focus on what you can change, (and don’t waste time on the things you can’t)

Throughout our chat, I’m struck by Kathleen’s ability to make peace with the things she couldn't change, but stand her ground for the things she could. I asked her how she felt when the men came back from the war, and the women were unceremoniously let go without so much as a thank you. “I can remember in my last pay packet at Brown Bayley, when I opened it there was a note inside that said we no longer require you,” she says. “But I mean the men were coming back from the war. It was only fair they wanted their jobs…”

However, many years later, something was done. In 2009, Kathleen famously sparked the Women of Steel campaign with one phone call to The Star. She was watching a programme celebrating the Women’s Land Army, and was furious that women like her were still missing from history. After their seven year campaign culminated in the unveiling of the statue in Barker's Pool, she quietly went back to her normal life, content with having passed her story on to the next generation.

Lesson 6. Love deeply

“I still talk to him everyday.” says Kathleen, gesturing at a framed picture on the sideboard of her beloved Joe, who died in 2008. “When Joe came home he needed a lot of looking after because he suffered from combat stress. It took just one day for him on D-Day to practically mentally finish him off, you know, just fall to pieces. And there wasn't the help there. He was 80 before someone came from the War Department to see how he was…”

She shows me a picture of her and her daughter visiting Ver-Sur-Mer in Normandy on Remembrance Day. They were standing by the very sea wall where Joe had been placed, injured, and Kathleen swore she could feel him shaking her. “It was just as though Joe had got hold of my shoulders and he was shaking me,” she says. “I could not stop shaking from head to toe and I was crying at the same time because I felt… a closeness of Joe…whether it was I was thinking so deeply about what caused it or whether it was Joe shaking me I don't know…Do you think such things can happen?” she asks. I nod. “Yes, yes, I do.”

Lesson 7. Keep doing what you’re doing for as a long as you can

“Keep doing what you're doing for as long as you can,” she says when I ask her what advice she would give to women today. “Just because you're getting old, don't ditch things, carry on doing them,” she adds. “That's my philosophy. I mean, up to a year or so ago, if anybody had said to me, will you come and play right half in my hockey team, I'd have said yes.”

“Joe and I used to do a lot of walking. And I had a job keeping up with him because he was in the infantry,” she continues. “I don't have carers, not as yet, probably someday I will have to. For now, I shall look after myself.”

Lesson 8. And finally, invest in the best haircut you can afford

Our interview takes place a month before she is due to receive an honorary doctorate of engineering from the University of Sheffield. At 100 years of age, she will be the university’s oldest ever recipient. Kathleen shows me the letter, but there are more pressing matters on her mind — avoiding the ‘one-cut-fits-all’ fate of the visiting hairdresser.

“I don’t like my hair like a lot of older people do,” she explains. “They like it really curly, frizzy, and they like perms. I’ve never had a perm in my life. I’ve got two crowns as well, so it needs a professional cut…I am fussy about my hair,” she laughs.

She’s chuffed though, because her daughter, Julie, has just managed to get her an appointment at her favourite salon on Bocking Lane in time for the ceremony. I ask if I can take a selfie, which we both then review disapprovingly. But for the last time that day, Kathleen sets me straight with a final piece of wisdom. “No, nowt to worry about such things. You are what you are, and if people don't like it, say, right, buzz off.”

There’s one final piece of order — the publicity consent form — which she signs and dates, apologising for her shaky handwriting. When it comes to the ‘age’ box, she writes ‘100’ and we both fall silent, gazing at the enormity of such a number. Kathleen smiles. “Blimey. 100 years old,” she says. “How did that happen?”

Michelle Rawlins’ book Women of Steel is available from bookshop.org here.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

We're so close to hitting our long-term target of 3,000 members. If you've been enjoying our work and believe in the importance of local journalism, please join up now. You will be able to get your membership for just £4.95 a month for the first three months, a £4 discount from our usual price.

In return, you'll get access to our entire back catalogue of members-only

journalism, receive eight extra editions per month, and be able to come along

to our fantastic members' events. Just click that big red button below.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Tribune and reach over 30,000 readers, you can get in touch or visit our advertising page below for more information