“It’s time for Gupta to go,” said Marie Tidball, Labour MP for Penistone and Stocksbridge. “He has run out of road; his chaotic ownership must end now.” Her unequivocal statement came the day before one of Sanjeev Gupta’s businesses, Liberty Steel, was to face a crunch court case at the High Court in London.

Liberty — part of Gupta’s broader GFG empire — employs hundreds of Tidball’s constituents at the steelworks in Stocksbridge, so it’s quite something for her to call for his ousting. Stocksbridge is steel, an industry already under massive pressure, and it’s not like there’s a queue of multimillionaires lining up to buy British steelworks. But she, like many others, has reached breaking point.

That group includes the workers. “New, responsible ownership is needed to give the business the brighter future it needs and deserves”, said Roy Rickhuss, general secretary of steelworkers' union Community this week. And it includes Liberty’s many creditors, one of whom was anonymously quoted by the BBC this week saying: “Of all the owners of this plant we've worked with, Liberty Steel is the worst. You don't know if you're going to be paid from one day to the next.”

Nicola Gupta, Sanjeev’s wife recently revealed in a Radio 4 profile that the first dance at their wedding was The Gambler by Kenny Rogers. (“You got to know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em. Know when to walk away, and know when to run.”) Gupta is the man who took the big bet worth billions — that money could be made in British steel. Back then, in 2016, he was hailed as the “saviour of steel”, with everyone from the then Prince Charles to Prime Minister David Cameron praising him. Now, things look rather different, and Gupta faces the equivalent of being bundled out of the casino, desperately protesting to security that he’s good for his debts.

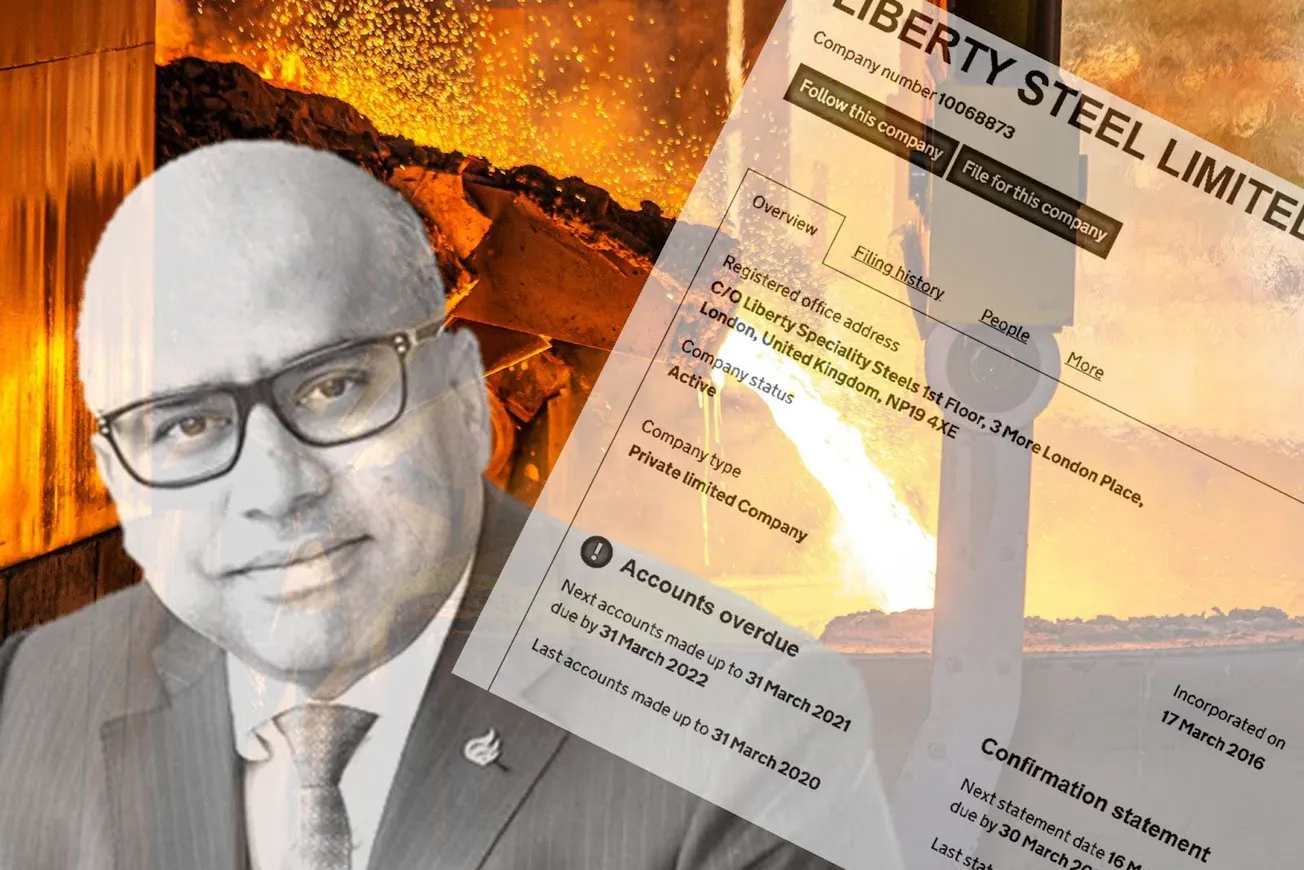

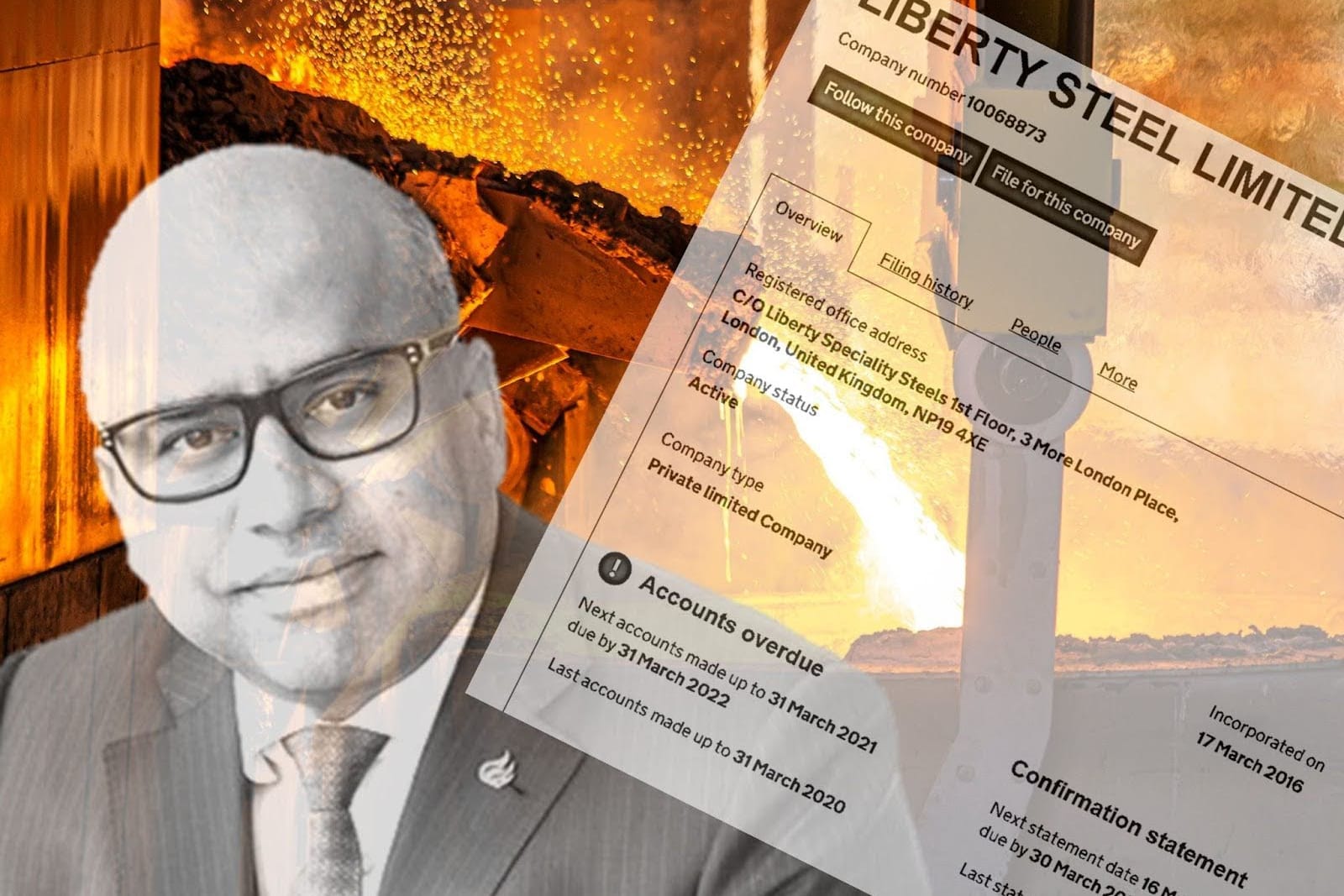

The government could have called time on Liberty some time ago. Last year it was revealed that Gupta was facing criminal charges for his failure to file accounts for 76 companies, enough to declare him insolvent (a look at the filings for Liberty show accounts overdue by more than three years). But it’s the creditors who have finally snapped and decided to drag Gupta through the courts.

Gupta managed to stave off a winding up appeal in November, getting another six months to try to sort things out. But various restructuring plans have come and gone. No-one, it seems, has been convinced that they are worth the paper they’re written on. It’s taken Harsco Metals Group, who have an office in Rotherham, to decide the only way to get some of the £4 million they claim they’re owed is for the Liberty to be liquidated, and its assets sold.

'Two drunks holding each other up at the bar'

Born in the sprawling Punjabi city of Ludhiana in 1971, Gupta was one of the lucky ones. The son of a wealthy industrialist, at the age of 14 he was sent to boarding school at St Edmund’s College in Canterbury. From there he went to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied for a degree in economics and business management. Even then his business interests were his main focus. While still at university, he began selling chemical products in Nigeria, using his college dorm room as the registered company address, something which repeatedly got him into trouble with the dean. While he was still a student, Gupta’s company was generating £1 million a day.

20 years later, with his business reporting annual revenues of £3.6 billion, Gupta launched a bid that would see him hailed as the saviour of the British steel industry. After purchasing his first steel factory in Newport, South Wales in 2013, he acquired further facilities in the West Midlands and Scotland, before launching an audacious bid for Tata Steel’s UK based operations in 2016. The following year he was able to secure Tata’s Speciality Steels business, including its factories in Stocksbridge, Rotherham and Brinsworth, in a deal worth £100 million.

That immediately made Gupta the most important person in the UK's steel industry. “His whole plan was to become too big to fail”, one source who has watched the drama unfold told us.

That would be put to the test in 2021, when everything started to go wrong. Many had wondered how, exactly, Gupta had managed to go on such a spending spree, which extended well beyond the UK. It wasn't easy to find out — the business empire is a web of private companies that have little requirement to publish such information. But it later emerged that one big company was behind the funding: Greensill Capital.

Greensill, in brief, specialised in supply chain finance, where a contractor who is waiting to get paid can get their money early from a finance firm, who in turn claims the money back from the original customer (taking a cut on the way). Greensill started to sell some of these bills on; much like before the financial crisis, bad debt was dressed up as good.

Greensill and Gupta both enabled, and depended upon, each other. They were “like two drunks holding each other up at the bar,” as one anonymous source told The Tribune. Or, if you like, they had a “pretty twisted symbiotic relationship”, as Angela Eagle described it when she was interviewing former Prime Minister David Cameron at the Treasury Select Committee. Cameron, who had been employed by Greensill, was being grilled after the company’s collapse. When that collapse happened in 2021, Greensill had $5bn of exposure to Gupta’s companies.

Many assumed that GFG would fold in the following weeks. But Gupta was determined that it was still the time to hold his cards, and embarked on an uphill battle to save the business.

In 2021, he sold three plants in Coventry, Kidderminster and Witham in Essex, as well as claiming £400m in loans from the taxpayer as part of a Covid scheme (that same year, Gupta bought a £42m townhouse in Belgravia — one of the most expensive UK property transactions in recent years — and threw a lavish birthday party on the Greek Island of Mykonos). It was also the year that the Serious Fraud Office launched an investigation into Gupta’s business empire, after allegations that some of the invoices being used to underpin the Greensill financing were fraudulent — stemming from companies that say they never worked with Gupta. In 2022, HMRC sought a winding up petition over an unpaid £26 million tax bill, a case that was later dropped. And in 2023, Gupta’s landlord and a US investor followed suit.

There's just one week left to claim our Spring offer. Hit the button below to support local journalism and read all our pieces. Only £4.95 for the first three months.

The turmoil had begun to affect day to day operations at Liberty’s facilities in South Yorkshire. Last year, the Sheffield Star revealed that staff in Stocksbridge and Rotherham weren’t paid on time in October while the company’s pension contributions had not been made since September. A piece in The Guardian this week revealed for the first time that two of Liberty Steels’ plants (the one in Rotherham and another in Motherwell, Scotland) had produced no steel at all since July 2024.

While the firm has managed to stagger, punch drunk, through the last four years, this week it felt like the endgame. A plan to restructure its debt was withdrawn after agreement with creditors could not be reached. And at the High Court on Wednesday, one of Liberty’s creditors sought a winding up petition over unpaid debts of £4 million.

However, just when the net seemed finally to be closing on the Gupta empire, they were granted another stay of execution. At the hearing on Wednesday, lawyers for Liberty revealed that a potential buyer had been found and asked the court for an adjournment. Insolvency and Companies Court judge Sebastian Prentis agreed to postpone the winding up petition for eight weeks (until 16 July) to allow time for the sale of the company to go through.

'The nucleus of a really good business'

So who is this mystery buyer? And what’s going to come next for Stocksbridge and Rotherham’s steelworkers?

Outside the Stocksbridge steelworks on Wednesday, people were tight-lipped about what the future might hold. Enquiries were met with a brusque “no” or else completely ignored. “You’re the last person I want to speak to,” said one man as he rushed past.

No-one The Tribune spoke to knew who the buyer was, or even if there definitely is one — there is some speculation that this might all be a wheeze to buy Gupta a bit more time, with a “straw man” offer being put in by a willing friend.

But many in Stocksbridge and Rotherham will be looking to another party: the government. They’ve recently stepped in at British Steel in Scunthorpe, and Forgemasters in Attercliffe is now nationalised. Is the only future for UK steel production to go into the taxpayer’s hands?

Colin Richardson, a journalist specialising in the steel industry, said that while it is true that UK steel manufacturers have faced exceptionally difficult trading conditions in recent years, it would be wrong to place all of Liberty’s problems down to market conditions. The main problem all UK steel manufacturers face is the cost of energy, where firms pay more than their counterparts in Europe, Asia and the United States. However, the other issue affecting UK steel firms, cheaper imports from abroad, has been less of a factor for Liberty’s factories in South Yorkshire due to the quality of steel it produces. “Speciality Steels make really high grade, high-tech, low volume steel,” says Richardson. “It has the nucleus of a really good business.”

Richardson believes the business definitely does have a future, but that it is unlikely to attract the investment it needs under the current management. As to what will happen now, there are two options, he thinks. Firstly, the government could step in to bundle it with the British Steel plant they have just nationalised in Scunthorpe, in the hope of creating a more compelling investment opportunity for a private buyer. Alternatively, the firm could enter administration before being bought out at a later stage. This would probably need the government to provide some cash to tide the business over while a new buyer could be found, but was the likeliest option, he added. Either way, there will be prospective buyers sniffing around. “There's definitely going to be people who are interested in acquiring it, but I don't know who they are,” he said.

Could Gupta have ever been the white knight that was promised? People we have spoken to say no.

From an early age, Gupta had great success in commodities trading, buying and selling everything from steel to sugar and chemicals to frozen chicken feet. 20 years of successful trading had made him a very rich man, and he wanted something to show for it. British steel was available at bargain basement prices and being a steel man allowed him to follow in the footsteps of other Anglo-Indian businessesmen and businesses such as Lord Paul and the Tata Group. But trading in commodities is much easier than running a steel plant, and buying big into metal was always a big gamble. The burgeoning relationship with Greensill only served to cover up the mounting problems and delay the inevitable.

No-one knows exactly what will happen next. But Marie Tidball MP and the steelworkers of Stocksbridge and Rotherham are likely to get their wish. Sooner or later, Gupta will be gone.