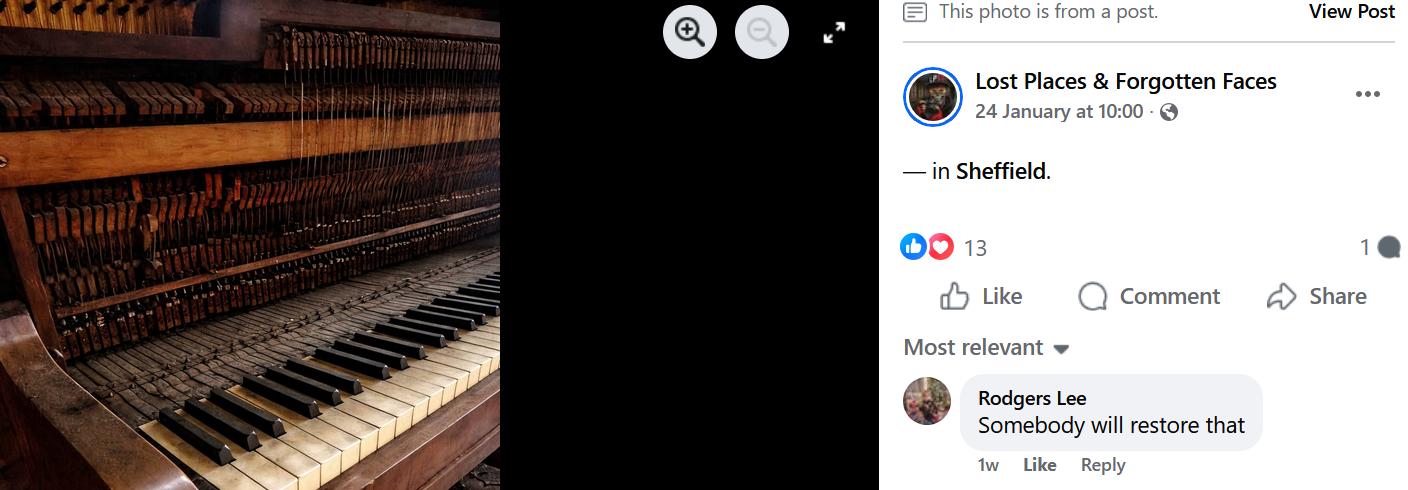

As with so many AI images, it’s the little details that give the game away. A logo on a cardboard box with uneven lettering, one not tied to any company in the real world. A piano with keys in the wrong order. Lost Places & Forgotten Faces — a full-time professional trespasser who tells me Sheffield is “is probably [his] favourite city in the UK to explore” — seems to have known better than to give some of these pictures, from inside The Adelphi in Attercliffe, to the local papers which eagerly document his exploits. The photos he demonstrably stole, however, he was more than happy to share.

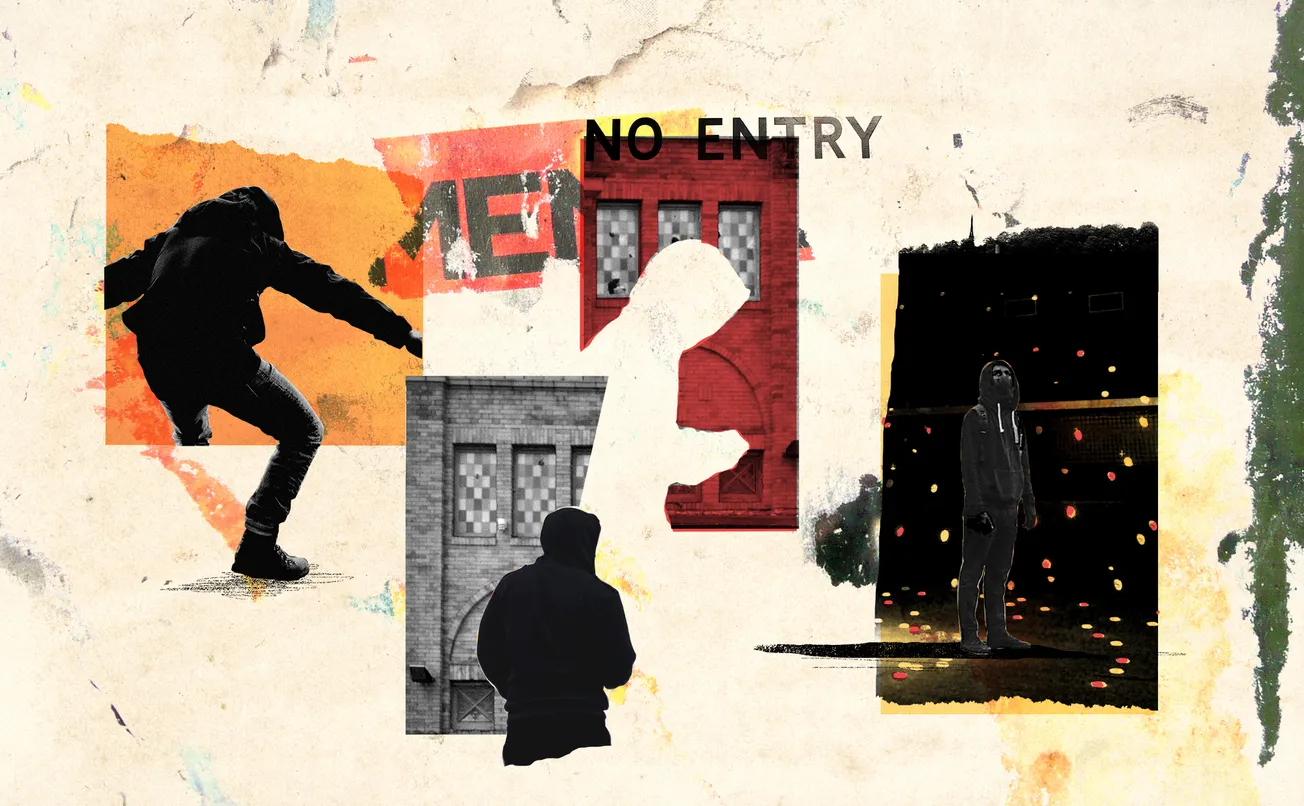

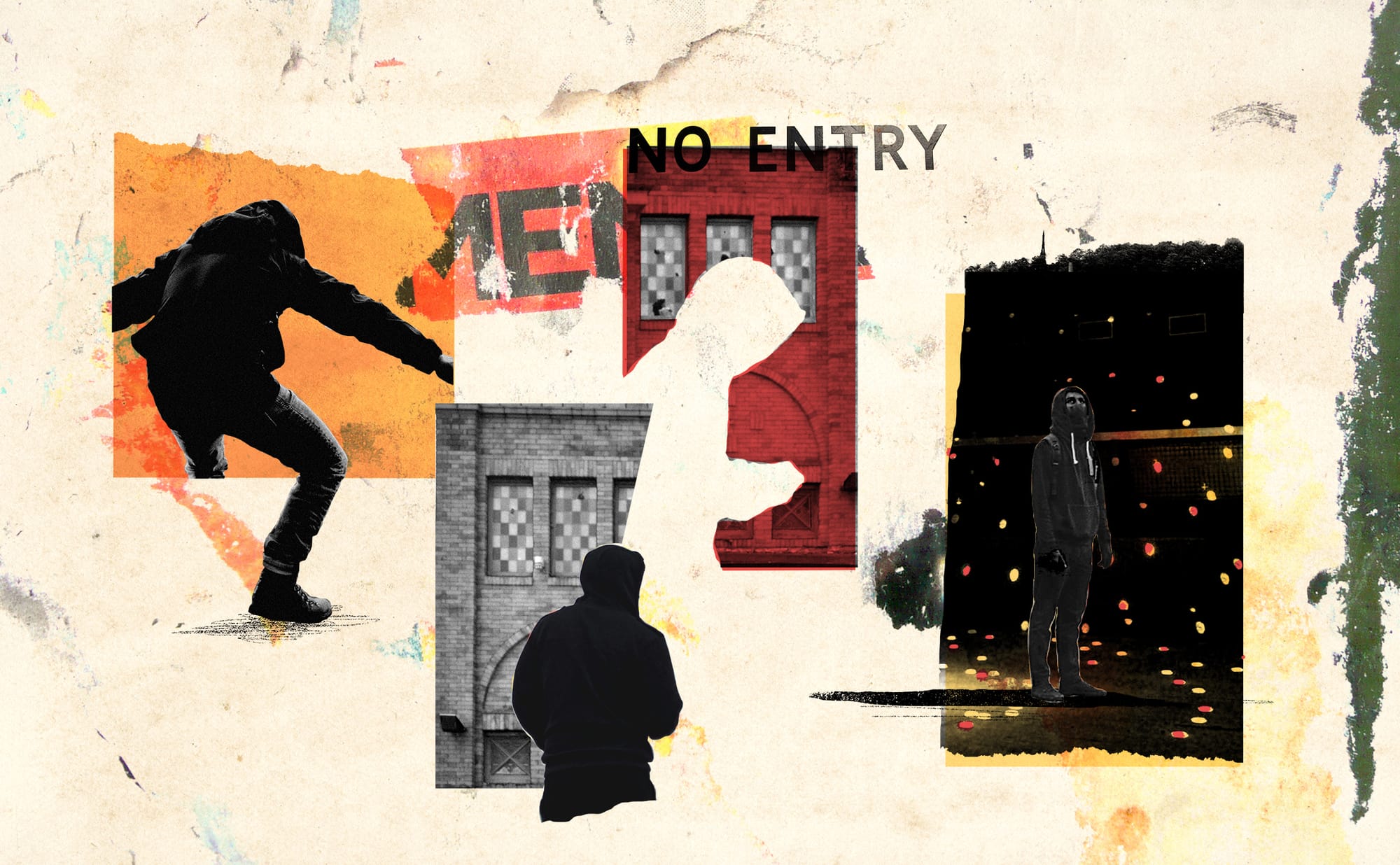

Urban exploration (or “urbex”) is the practice of sneaking into abandoned buildings or places never intended for casual visitors. It is, as one explorer puts it, “an underground hobby that’s in a grey area of the law”. With a few exceptions, trespassing is a civil rather than criminal offence, meaning urban explorers would only appear in court if the building or landowner sued for compensation. On the other hand, it’s obviously not something you’re allowed to do. Every urban explorer I speak to has been ejected by security or police on at least a handful of occasions. For some of them, the illicit thrill is part of the appeal.

It might surprise you that anyone could make a living this way, especially since (as a reporter from the Sheffield Star helpfully confirms) newspapers aren’t typically paying for these pictures. Instead Lost Places & Forgotten Faces — who claims to be a 25-year-old from Harrogate called Matt — tells me he “brings in consistent revenue” from his monetised social media platforms, while also selling books of his photographs on the side. He’s already published Abandoned Yorkshire, Abandoned Sheffield and Abandoned Leeds, while Abandoned Bradford and a beginner’s guide on urban exploring are currently in the works. “So this job keeps me very busy!” he adds.

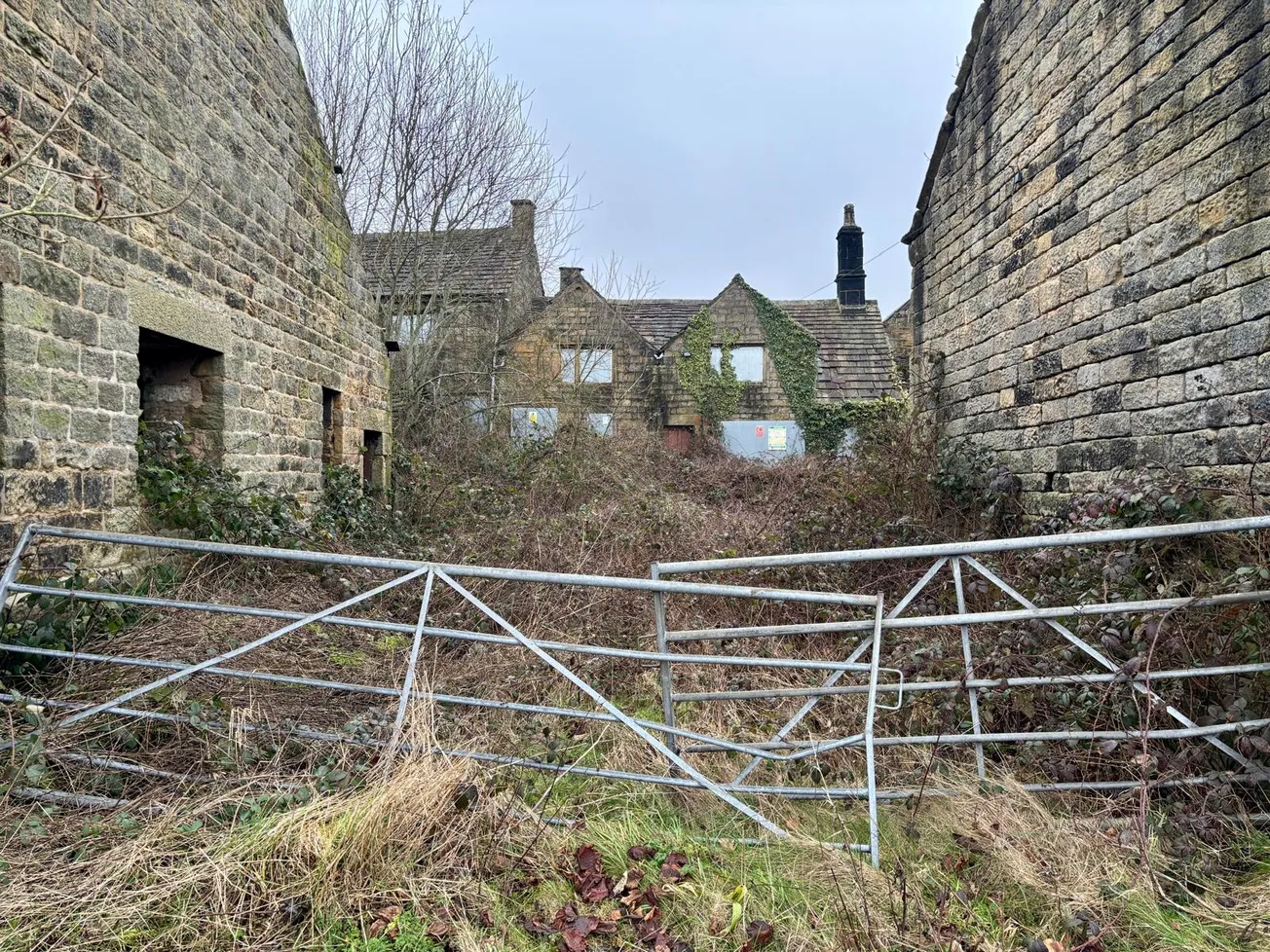

Unsurprisingly, not everyone approves of how Matt makes his living. Last month, Sarah McLeod, CEO of the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust in Rotherham, publicly condemned him for posting pictures from inside disused buildings the trust plans to demolish. “This trespasser has ignored warning signs and security cameras to enter buildings on our site which are in a dangerous condition,” she told the Rotherham Advertiser, not only risking his life but also “causing expensive health and safety concerns” for the trust. On his official Facebook page, Matt was unrepentant. “Sorry not sorry!” he wrote.

In his conversations with me, he seems far more concerned by the “bad reputation” urbex currently has. “It would be nice,” he writes, if The Tribune could shine “a more positive light on the hobby”. Rather than writing about the “baseless and simply ridiculous” rumours being spread about him by other urban explorers, perhaps I could be highlighting his philanthropic efforts. A few years ago, for example, he donated some of his LPFF branded hats and hoodies to a homeless shelter in Sheffield. Every October, he explores in pink clothing to raise awareness of breast cancer. “I always strive to use my platforms for good causes,” he writes. (When I ask if he also donates any of his income alongside raising awareness, I receive no response.)

According to Matt, even his motivations for urban exploring are largely innocent. “I love architecture and retelling stories of bygone buildings,” he writes. “I love it when people comment on my explores who used to live, work or study there and the memories that come flooding back for them.” When he spots two people in his comments who have lost touch and find each other as a result of his photos, it is “the best part of this job,” he says.

So why — given butter seemingly wouldn’t even think of melting on Matt’s tongue — do so many other urban explorers despise him? “He doesn't give a fuck about preservation, history or genuine exploring as a hobby,” one critic insists, while another describes him as a “massive troll who's trying his best to piss off as many people in the UK urbex scene” as he can. When I ask for opinions on 28DaysLater — an urbex forum created in the early 2000s, which banned Matt some time ago — I immediately receive several responses detailing his sins. Within a few days my post is deleted, although not before a moderator changes its title to “Lost Places & Forgotten Faeces”.

From the few people who do agree to speak to me, I am able to learn a fair bit — both about Matt’s behaviour and about the underground, secretive world that has largely spurned him. While some of his transgressions are straightforward, much of the animosity towards him has more to do with the unspoken honour code of this tight-knit community. As one local explorer, who asks to remain anonymous, tells me: “He’s giving us urban explorers a bad name.”

Like his use of AI, the fact Matt steals photos is easy to prove. Last week, for example, he shared the above photo on Facebook from the Megatron beneath Sheffield, actually taken by Paul Powers, a 45-year-old urban explorer, in 2013. While sometimes Matt alters images to hide his theft, such as by reversing them or enhancing them with AI, he doesn’t always bother. “People have confronted him before, but he just deletes the comments and blocks them,” Paul tells me.

The photos from The Adelphi that Matt gave to The Star last month include several showing vacuum cleaners and boxes, which a council spokesperson confirmed were removed from the building three years ago. They also include stolen photos never taken inside the building at all. These images — which show a number of cassette tapes from a clubnight called Uprising that took place in the building in the late 90s — were pinched from a Facebook group for tape collectors. The man who posted them tells me they are of his personal collection and were taken inside his home.

For newspapers like The Star, this kind of deceit is profoundly irritating. “It’s clear he goes to quite a lot of places so why does he feel the need to take other people’s content?” one of their reporters muses, explaining that they found out after the article went live. “It must be some kind of stolen valour, it’s bizarre.” The man who took the photo of the tapes says he worries the misleading impression that there are vintage tapes inside The Adelphi could inspire potential burglars. “Tapes are worth money now,” he points out. “It could encourage people to go hunting.” Cllr Ben Miskell makes a similar argument when contacted by The Tribune. “The concern from the council’s perspective is that posting inaccurate or outdated information can encourage others to attempt to access the site,” he wrote.

Hi, Victoria here. Thanks for reading my piece about the murky world of urban exploring in Sheffield. For us to be able to go so in-depth and get into stories in ways other journalists don’t, we need the support of our readers.

If you sign up for free, you will get all our journalism sent directly to your inbox. Not to mention, you’ll be joining a community of like-minded Sheffielders who understand the importance of well-researched journalism. Why not give it a go?

Even urban explorers who haven’t had their photos stolen tell me that Matt’s love of press attention “is a big urban exploring no-no”. While the more obvious locations are frequently shared on forums like 28DaysLater, many explorers try to keep the bulk of sites hidden from the general public. Photos from these spots are instead shared in private group chats, with trusted members of the community.

Dr Kevin Bingham, who wrote a book about urban exploring five years ago while studying at Sheffield Hallam, tells me explorers are often accused of being “gatekeepers” because of this veil of secrecy. While he readily admits some “are quite tribal and would fiercely repel outsiders”, he argues many are actually motivated by a desire to preserve their spots. Sites that become too public are inevitably vandalised by local teenagers or sealed up by the owner; being covert “means sites can remain open a lot longer, so more people can get in and see them,” he explains. One urban explorer points me to several examples of buildings being damaged in the immediate aftermath of Matt highlighting them, including an abandoned warehouse in Sheffield that caught fire the day after his photos were published in the press.

This secrecy also means that, in some cases where Matt claims to have been the only person to access a site, he is actually stepping on thoroughly trodden ground. In fact, even when there is evidence demonstrating another explorer has beaten him to it, he seems happy to claim he was the first. When I ask him about his favourite sites in Sheffield, he writes: “I'd say the fact that I am the only urban explorer to document both Weston Tower and The Adelphi Picture Theatre means that those two explores mean the most to me.” When I direct him to photos posted from these buildings in 2014 and 2011 respectively, he ignores the remark. “He has a massive ego for no reason, thinking he’s the best explorer out there,” one critic tells me. “But a lot of people have been doing it way longer than him, done more locations than him, and respect the hobby more than him.”

According to Matt, his critics are simply jealous of his success. “I don't want this interview to be too negative, as I always try to be positive,” he insists, “but, sadly, the hobby of Urban Exploration can be quite toxic amongst participants. It's a shame people are like that as it sometimes can affect my mental health, which I am a strong advocate for protecting. I believe the fact I get to do what I love as a full time job makes other, less prominent explorers jealous.” Despite this, and despite the number of people who say otherwise, he insists his reputation in the community is mostly positive. “I regularly collaborate with others and always help new explorers get started with advice and support.”

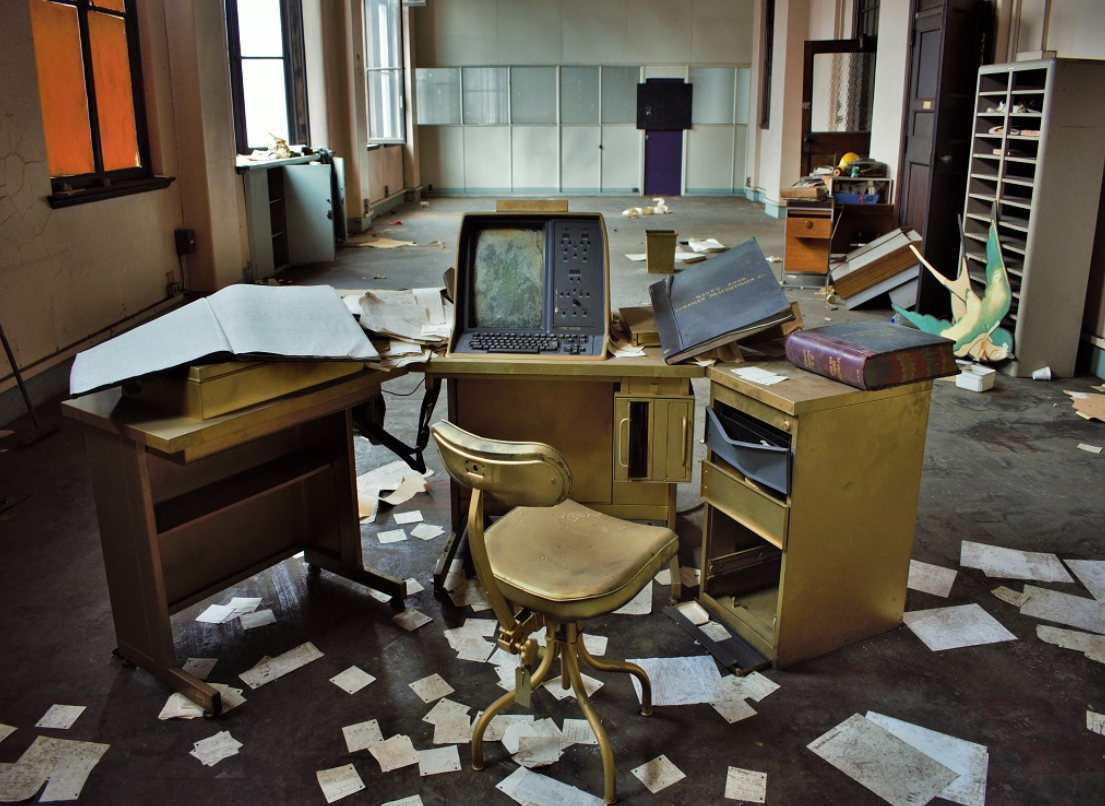

According to Dr Bingham, who lives in Rotherham and was himself a passionate urban explorer for many years, people like Matt are an example of a new faction within the urbex community, brought about by the rise of social media. (“The new breed of Facebook explorer,” as one member of the old guard puts it.) “Over the years, urbex has become a very trendy thing to do,” Dr Bingham says, in part because of how much even those with no interest in participating enjoy the photos that come out of it. “There’s a big theme in the wider literature about the ‘aesthetics of decay’ and lots of arguments about why it fascinates people. Whether it’s tied to nostalgia, whether it makes people more reflective about life and death or whether it’s just the general beauty of it.”

The unfortunate side-effect of this fascination, however, is that the hobby has become increasingly image-focused. “For some people, it’s almost become a competition to get the best images, whereas back in the early days[...] we were just doing it for the pure thrill”. It’s one of several factors he says have led him to drift away from urban exploring, alongside the decline in the number of suitable spots. “Urbex became a little tedious, especially around Sheffield as sites started to disappear. It’s certainly not the wonderful place it used to be in terms of abandoned buildings, lots of things have been knocked down or regenerated,” he says.

Paul Powers, by contrast, tells me he can’t imagine ever losing his passion for urban exploration, despite the fact he’s been doing it for around 20 years. There are explorers still at it in their 70s, he points out, and it’s clear he hopes to be one of them. At his most active, Paul was visiting two or three locations every day, while now he tends to go exploring once every few months. He reckons that, even if he’d maintained his previous frantic pace, he would never manage to exhaust everything. “There’s always hospitals closing and care homes closing, so there’s always going to be somewhere to visit,” he says.

That said — though Paul has visited the odd building he found particularly enticing, such as the old Sheffield Crown Court — he is first and foremost a fan of drains and mines. “It’s going to sound really weird but, when you’re underground, it’s very peaceful,” he says. “There’s none of the pressure from people above, none of the stress. It’s almost meditative.” He’s particularly fond of Victorian drains, enjoying how much care was taken over the design of something most people would never see. “They’re so ornate, I feel privileged to have experienced some of them,” he tells me. “A lot of the stuff built now is concrete pre-fabs. Although, that can still be interesting.”

What Paul is doing is, however meditative, not entirely safe. He admits he’s broken his wrist before, after slipping and falling on a rock, and that people in his life sometimes worry he might drown in a flash flood. There’s also a risk of encountering dangerous gases underground; he knows one explorer who emerged from a drain with a collapsed lung. “The danger is probably part of the appeal, to be honest. It’s a little bit of an adrenaline rush entering somewhere that’s not been seen for 30 to 40 to 100 years.”

Paul can also understand why many urban explorers object to anyone bringing too much attention to the hobby, although he notes Matt isn’t the first person to be criticised for doing this. Decades ago, “when urbex was really underground,” an academic and explorer called Bradley Garrett wrote a number of books about the practice. “It shone a spotlight on urbex and people really hated him for that,” Paul says. “People worried about the attention it was bringing, urbex was mentioned in parliament at the time.” There were concerns that it could prompt the government to introduce new laws to crack down on the pursuit. Even if they did, Paul insists this wouldn’t stop him. “I only get caught once every few years and, even if it became a criminal offence, it would probably not be worth the effort of going to court for them.”

On the handful of occasions Dr Bingham was caught, he tells me the police were not too bothered once it became clear he and his fellow explorers were not there to steal. “We got caught in Sheffield exploring the Ski Village when it was first abandoned, we went out with sleds and spent an afternoon sledding down it,” he recalls. “The police were really nice about it, they were joking that they were going to get the riot shields out and have a go themselves once we were gone.”

Thankfully for the urbex community, trespass remains a civil offence, provided explorers are able to get in without breaking and entering. For those more interested in abandoned buildings, as Dr Bingham was, part of the appeal is the “puzzle” of working out how to do this. “We sometimes spent days figuring out what security there was and where the gap might be,” Dr Bingham tells me. “That was often more exciting actually, it was almost anti-climactic by the time you got in.” This is why he can’t really wrap his head around those like Matt who are happy to share information about how to access sites. “For me, that takes something away from it because it doesn’t entail as much research.”

Ultimately, despite their scorn for the way he operates, most urban explorers I speak to are convinced Matt is a problem that will eventually go away on his own. “If you’re stealing pictures or causing problems, you’ll get shunned out of the community and then good luck finding somewhere to go, no one will share information with you,” Paul says. “But, as long as people are giving them attention, they will keep doing it.”

Hi, Victoria here. Thanks for reading my piece about the murky world of urban exploring in Sheffield. For us to be able to go so in-depth and get into stories in ways other journalists don’t, we need the support of our readers.

If you take out a paid membership, you get two months free and you’ll be able to read all our members-only journalism. Not to mention, you’ll help us carry on reporting in ways few journalists have time for. You can also join monthly, so why not give it a go?

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Tribune and reach over 30,000 readers, you can get in touch or visit our advertising page below for more information